On the down side, it had a staggering lack of leadership, a greedy mob of owners who took the company public, countless conflicts of interest among the membership and no regard for controlling costs.

In its heyday, both Bernie Ecclestone and Bill France Jr feared CART. In its final days, neither Formula 1 nor NASCAR gave it a second thought. It was born of necessity and died of neglect.

“We had something very special for a long time,” laments Mario Andretti, the 1984 CART champion who drove for Paul Newman and Carl Haas for 12 seasons before retiring in 1994 at the age of 54.

By the time Newman/Haas opened its doors in 1983, CART had a nucleus of Pat Patrick, Roger Penske, Jim Hall and Gurney. Can-Am survivors Doug Shierson and Rick Galles joined up in the early ’80s along with Jim Trueman. Patrick and Penske had taken the offensive, spent some of their own money and scored PPG Industries as a title sponsor. (USAC had Marlboro as its title sponsor back in 1971 but lost it after only a year because of incompetence).

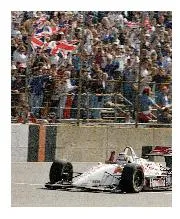

1984 CART champion Andretti lamented the demise of the series and US open-wheel racing

Getty Images

Midway through the ’80s, CART controlled all of Indycar racing except Indianapolis and an uneasy truce existed each May. On the racing side, CART had replaced F1 at Long Beach, branched out into Canada, found a popular home at an airport in Ohio and rejuvenated road racing in North America at Mid-Ohio, Laguna Seca and Elkhart Lake.

But off track there was a flaw that would prove fatal down the road. Not only could the owners seldom agree on anything, they usually opted to pick a president who could be manipulated or knew nothing about racing – or both. The litany of lawyers and leeches who occupied the front office was rivalled by the revolving door in the marketing department. Patrick and Penske called the shots and there was a distinct divide between the haves and have-nots by the late ’80s.