“That’s one part of it. Another is that almost all of the successful driver/sponsor relationships below F1 are really patronage dressed up as sponsorship. So a driver will go off for a weekend of fishing or golf with his mentor. But the president of a corporation couldn’t turn round to me and say ‘let’s go spend the weekend together,’ because it has all sorts of other connotations! We’re just that seemingly little step away from proving things but we cannot quite make that step because of the little social things that prevent financial muscle being put behind a woman driver.”

It hasn’t always been so. Back when motor racing didn’t have so many layers, when a driver with ability could display it at a fairly high level without first having to get through the jungle of junior formulae, there was a woman who had it all — Elizabeth Junek. Her form was sensational but frustratingly brief.

The Czech was married to a Prague banker, Cenek Junek, who funded their joint racing exploits in the 1920s. On the track, though, it was Elizabeth who wore the trousers. Her first international event was the 1927 Targa Florio where she ran an early fourth ahead of eventual winner Meo Costantini before her steering broke. Junek followed this up with a win in the 1.5-3-litre class of the German Grand Prix on her first visit to the Nürburgring!

Wilson qualified 16th for Tyrrell at the 1981 South African Grand Prix

DPPI

The following year Elizabeth Junek launched another attack on the Targa and this time left the men open-mouthed. Her Bugatti lay fourth after the first 90 mile lap but on lap two she went into attack mode, and took the lead from Campari’s Alfa. Drivers of the calibre of Nuvolari, Divo and Materassi were eating her dust. The contest subsequently came down to a duel between her, Divo and Campari and the two men were only let off the hook when, on the final lap, her water pump failed, forcing her to back off in order to get the overheating car home.

Later that year she and her husband returned to the Nürburgring but Cenek Junek crashed fatally. Devastated, Elizabeth withdrew from racing and wasn’t seen again until the ’60s. Even as an elderly woman, her handling of Bugattis in historic demos suggested she still had a feel for those glorious days. Days when the lap timers would look in turn at their watches and then each other as the blue Bugatti sped past.

In the 1930s, Kay Petre added glamour and also a steely determination to the British racing scene. She lapped a 10.5-litre Delage at almost 135mph around Brooklands, but unlike Junek, she never got to race at the top level of international competition.

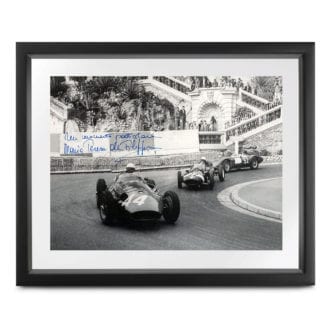

In 1958, Maria Teresa de Filippis campaigned a Maserati 250F in the world championship and whilst no threat to a Moss or Brooks, she was certainly worthy of her place on the grid. It would, however, be another two decades before the next woman arrived in F1. Lella Lombardi recorded her place in the history books when she took sixth place in the foreshortened 1975 Spanish Grand Prix to score half a point. She wasn’t the most gifted of the various works March drivers that year, but she was better than was realised at the time, as Robin Herd recalls: “She always complained that her car had vicious oversteer and we just said ‘yes, well that’s how they are, you just have to get used to it’ The following year we put Ronnie Peterson in that car and he came in saying ‘this car has got vicious oversteer.’ We checked and found out there was something dreadfully awry with the chassis.”