Max Mosley: Formula 1's saviour or sinner?

In May, motor racing lost one of its most notorious characters, but was Max Mosley the hero or the villain within his own lifetime? Throughout his career as a barrister, amateur driver, constructor and eventually head of the sport worldwide, he split opinion like no other. Damien Smith looks at his legacy

Surely things couldn’t get more political after Jean-Marie Balestre... could they? Buckle up, Max Mosley’s FIA presidency was far from straightforward

No breed is more effective – or deadly – than the poacher turned gamekeeper. As the ‘M’ of March, that arch ‘disruptor’ of constructors, Max Mosley served the ideal apprenticeship during the 1970s for the ultimate switch from anti-establishment to the FIA presidency that became his calling. In Bernie Ecclestone, for all their differences and contrasting backgrounds, he found a kindred spirit as together they turned Formula 1 on its head through 30 exhilarating and tumultuous years. When Ecclestone described Mosley as “like a brother” following his friend’s death aged 81 on May 23 2021, it was no glib cliché said for effect. He meant it.

Individually and together in pot-stirring partnership, few men can claim to have influenced and shaped F1 to the same degree. Both found their limits as racing drivers all too easily. Neither were engineers nor designers who shaped F1 in any direct, inspirational sense as Colin Chapman did. And while Ecclestone tasted much greater success at the helm of Brabham than Mosley at March, they were never cut from the same cloth as team ‘lifers’ such as Frank Williams, Ken Tyrrell and Ron Dennis – men with whom both would clash through the years. Yet for all the wins, world titles and sporting history these team owners would orchestrate, the bigger picture was always centred on Mosley and Ecclestone, and their desires, demands and sheer lust for control over a fiefdom they dominated.

From the governance of increasingly stringent and convoluted technical regulations to dollar-churning TV rights, the expansion of increasingly exotic race schedules to eye-watering sponsorship and team budgets, this double-act diced up grand prix racing between them, sparking a carefully evolving revolution that turned F1 from a relative sporting backwater into a ‘major’ that punched at the same weight as the Olympics and football’s World Cup (except more impressively on a cycle that peaked every other week rather than every four years). Mosley deserves equal credit/ blame (take your pick) for almost every aspect of this incessant revolution – but more on the most significant: safety.

It’s an F1 irony that Mosley picked up the baton first grasped by Jackie Stewart, always a rival ‘big beast’ rather than a friend, with whom he first clashed in the days of the March 701 – and decades later cruelly dismissed as a “certified half-wit”. And yet on this one subject, the most vital of them all, they shared so much. Their most pointed difference, beyond the obvious personality clash, is how they will be remembered.

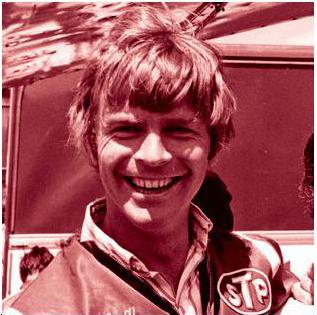

A fresh-faced Mosley during the early days of March.

A fresh-faced Mosley during the early days of March.

In Formula 2 action at Zandvoort in 1968. He co-founded the London Racing Team to enter the championship

McKlein

For all of his achievements – and they were both unarguable and many – Mosley’s legacy will remain disputed, tarnished beyond the point of salvation for many. To some extent, it wasn’t what Mosley did as FIA president that clouds our memory, but how – and with what motivation. There is also one episode of politicking around which his whole presidency revolves: his decision to hand the commercial rights of F1 to Ecclestone in 1995, in a deal that was eventually enshrined for 100 years, at the relative snip of $360m. This was Mosley’s Iraq war.

“It’s not what Mosley did during his presidency, it’s how he did it”

To his critics, including most vocally Dennis and Tyrrell, and at times also Williams, it was a form of ‘theft’ – even if such men owed Ecclestone a debt they could never repay for making F1 the cash cow they all milked, in one way or another. The constant debate and tussle over who ‘owned’ F1, a concept that was inconceivable to ardent purists, coloured Mosley’s terms of office all the way until he was finally forced to accept it was over at the end of 2009. In his defence, Mosley had to sell the rights to someone, in the face of the running battle he waged with the European Union and its ambitious, aggressive Competitions Commissioner Karel Van Miert, who insisted the FIA was breaking competition rules in its governance of F1. And in truth, who better than Ecclestone to own and run F1’s business, given his entrenched knowledge and experience? The problem was the deal left F1 vulnerable to become little more than a commodity ready to be stripped. The era of faceless private equity ownership, under CVC Capital Partners, led directly back to Mosley’s door and the agenda he and Ecclestone worked to. Surely the FIA president had the power, intellect and motivation to thwart such destructive forces and find a better solution than asset strippers, for the good of F1 – didn’t he? Instead, it has been left to successors Liberty Media and Jean Todt to unpick the knots. F1 is far from perfect today – of course it isn’t – but there is at least a sense of common purpose among F1, the teams and the governing body.

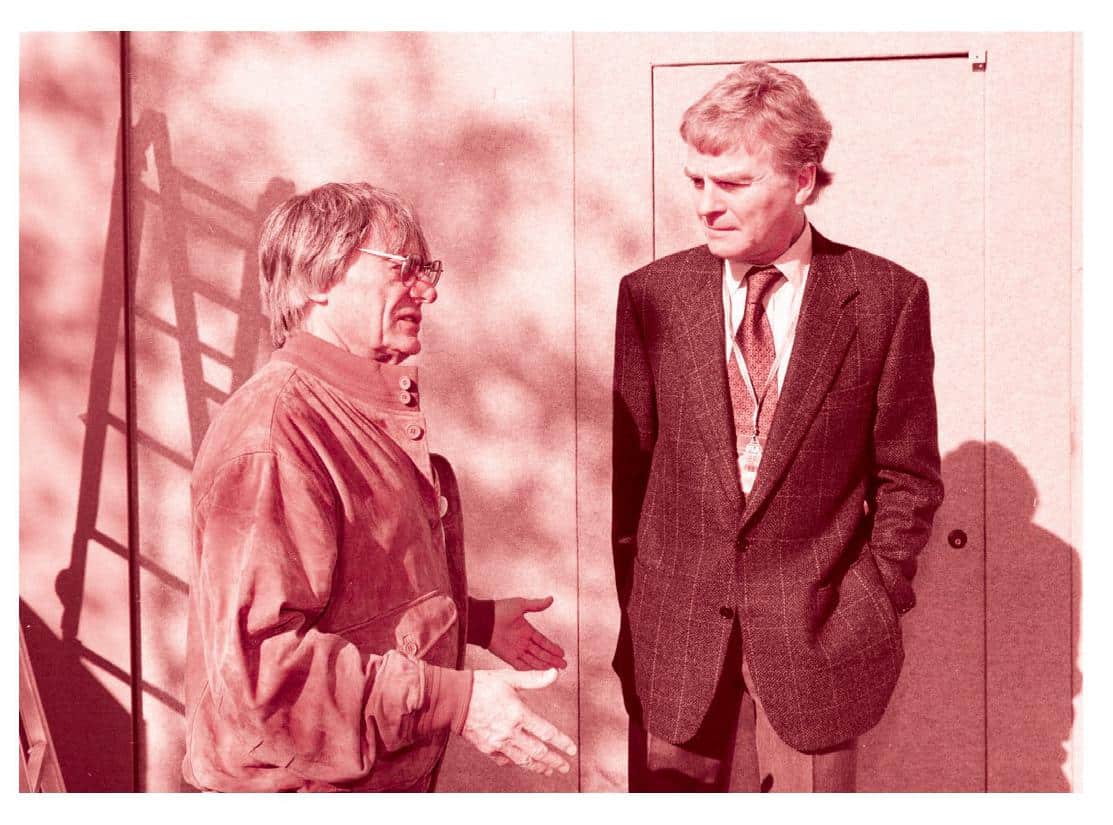

Best of enemies? Former McLaren head Ron Dennis converses with Mosley during the ‘Spygate’ saga. Mosley would later suggest Dennis was most of the reason for the $100m fine

The juvenile humour, the sniggering at others’ expense, apparently made Mosley engaging company for some, but such ‘wit’ was too often a display of the vindictive streak that powered key decisions in his presidency. ‘Spygate’, a $100m McLaren fine and the insult to Dennis that “five million [was] for the offence; 95 for Ron being a ****”; then there’s his hard-to-swallow insistence he’d managed the Michelin tyre debacle of the 2005 US Grand Prix as best he could; or how about bowling Silverstone an unplayable delivery by signing off Ecclestone’s malicious decision to schedule the 2000 British GP for April, thereby almost guaranteeing the farcical mud-bath that threatened the race’s future? All were examples of perhaps the most distasteful aspect of his presidency: that Mosley the legal eagle, with the towering barrister’s intellect and open superiority complex, never really considered the welfare of fans as a factor within his political web-spinning. The public were an irrelevance when it came to ruling F1 by the letter of the law. The catch-all rule of bringing the sport into disrepute was a running theme through his terms in office. Fans might argue he was guilty of the same offence, at least on their terms if no-one else’s.

Mosley was in his element when crusading to save the sport from itself, as he did so effectively in the mid-1990s when he pushed through significant technical changes in the name of safety, butting up against and defeating the stubborn resistance of blinkered F1 team principals. He was absolutely the right man for that job. And lest we forget, he pioneered the idea of a team cost cap – again in defiance of team principals who ‘knew better’ – while ushering in energy recovery systems in advance response to the gathering storm of climate change.

At times like these, his ability to see the wood for the trees was a blessing he deserves credit for. But there were times too when those same bosses and car manufacturer executives could legitimately ask: who would save the sport from Mosley?

Facing the media

In the end, judgements on his legacy, for good and ill, will remain subjective. You’ll have your own view. But it is hard to forget that when he succeeded Jean-Marie Balestre, his famously autocratic and puffed-up predecessor, a sense of relief mixed with new hope for governance grounded in sanity wafted around Mosley as he swept into office. Nearly two decades later, those self-same sentiments still wafted around him, this time on his way out.

Like Ecclestone, Mosley chose to divide and rule, which he did with an iron fist. He could have been a figure to unite, as a force of reconciliation – but altruism simply wasn’t his way. Instead, conflict, angst and opaque agendas were at the heart of Mosley’s reign, and so his epitaph can never be a simple, or spotless one. Perhaps that’s exactly as he wanted it. After all, the darkest corners are so much more seductive than the light.

Mosley quickly decided life behind the wheel wasn’t for him.

The life of Max

1940 Born in London

1964 Begins legal career after studying at Christ Church, Oxford

1966 Begins his racing career in club motor sport, before stepping up to European F2

1969 Co-founds March Engineering with Robin Herd, Alan Rees and Graham Coaker

1977 Leaves March and becomes legal advisor for F1 Constructors’ Association, FOCA

1993 Becomes FIA president for the first of four terms

1995 Sells F1’s commercial rights to Ecclestone

2009 Stands down from the FIA amid rules rows and legal battles

2021 Dies on May 23 after being diagnosed with cancer, aged 81

Ecclestone and Mosley hold court at a World Motor Sport Council meeting.