Then everything changed in an instant. The young man speaking in fractured, broken, halting English was in deep shit, but positively so. A miracle had taken place: he had got into F1, a world that only a year ago loomed in the far distance.

Kimi’s old friend Teemu ‘Fore’ Nevalainen has an interesting theory: “If the journey to fame had been longer and he had been given more time to prepare, I bet it would have resulted in a different Kimi from the one we’ve got. A more boring one, I’m quite sure. He would always have given the answers people wanted to hear.

“Now he says more in three words than the others put together.”

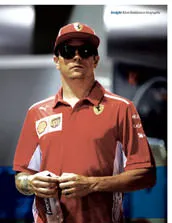

Kimi isn’t the first Finnish sportsman to shun the microphone, or to fear it. But he’s the first one whose reticence has become an international brand.

“The interviews irritated the hell out of me. I think they’re pointless.”

He struggles to cope with celebrity; it’s a bitter pill to swallow, a necessary evil. “It would be brilliant to drive in F1 incognito,” he says, and I make sure the Dictaphone stores this first sentence. And when he says it, Kimi knows that no such world exists or will ever exist. It’s possible to move a razor, or drive a lawnmower incognito, but not a racing car worth seven million euros.

“There weren’t that many interviews in karting, perhaps the odd one if you got to the podium. And that was true of Formula Renault, too. It didn’t feel that awkward in F1, but the interviews irritated the hell out of me. I think they’re pointless. It’s just the same questions day in, day out.”

I pause to think about Kimi’s relationship with the PR part of his job. Ferrari’s annual budget exceeds €400 million. The sum is off the scale and carries with it sponsors’ requirements and requests, fantasies and figures of speech. No one sees the bigger picture; everyone views things from their own angle, through a keyhole. And all you see through that hole is two drivers. One of them grants, reluctantly, a sentence or two, and scratches his ear.