Master craftsmen

This series has so far been uplifting – discovering traditional skills still being practised and passed on to a new generation of craftspeople. But I came away from Vintage Restorations with a profound sense of sadness. For 50 years John Marks has almost single-handedly refined his skills at refurbishing the instruments of classic cars, assembling a staggering reference library and suite of equipment, and yet as he contemplates retirement he says the operation has nowhere to go. “I’ve failed to find anyone to teach,” he says. “So we’re doomed.”

In terms of the national GDP this is trivial, but as John talks us through the resources, the knowledge and the intricate fettlings that mean he can repair and refurbish the chronometric rev counter on your Amilcar or print a new dial for your MG fascia, it seems a criminal waste.

Once upon a time John worked as an architectural technician but liked fixing mechanical things, and when he mended a car clock a friend brought him, it led to a stream of requests and then a business. All these years on he’s an international expert, entirely self-taught, with customers world-wide.

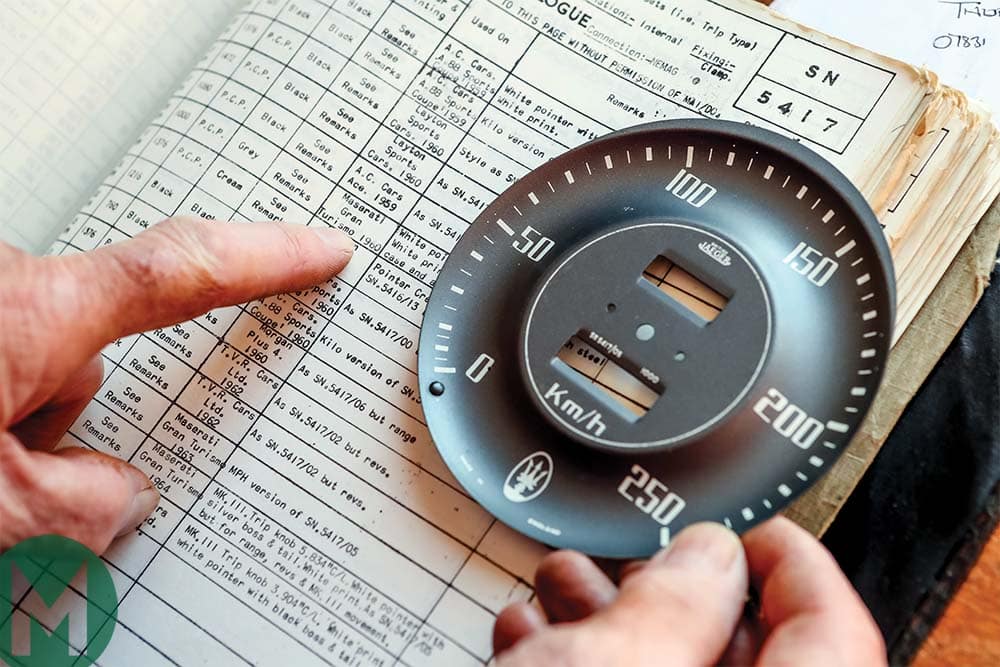

He’s been halfway to retiring for years, but the requests for help with rare or complex instrumentation keep rolling in, and John keeps sitting down at his bench to solve their problems. It’s a crowded, tightly packed premises, this, an old bakery in a residential street in Tunbridge Wells, yet it’s plainly tidy and well organised. In one room are racked hundreds of manuals from the likes of Smiths Instruments and Lucas detailing the exact specification of dials for an HRG or Daimler Conquest. Next along, rows of order books. “We’re on book 88 now,” says John. “I don’t know how many instruments we’ve restored altogether, but I think we’ve done 60,000 temperature gauges.”

Upstairs, via a striking metal spiral stair (“People think it looks smart but it was the cheapest thing at the time…”) are endless shelves and drawers holding dials, glasses, pointers, bearings, tubing, all neatly boxed and labelled ‘MG P-type oil’, ‘Bugatti T57 0-8000rpm’ and ‘Auto Union C’. Yes, when Audi, via Crosthwaite & Gardiner, was constructing its Grand Prix replicas it was John it turned to for instruments. He also made dials for the Buckminster Fuller Dymaxion, that bizarre grounded car-aeroplane that C&G built up for Lord Foster.

Although he can make any instrument from new, John is careful about originality: “If you send me an instrument for repair or restoration, that’s the one you’ll get back,” he says. “Barring any bits I need to replace, of course.” His spares supply is awesome – boxes of old dismantled speedos, milometers, gauges of all sorts, even supercharger pressure; oval, square, twin; from Smiths, Jaeger, Veglia and the rest. Especially precious are parts from chronometric instruments – the highest-quality mechanism that snicks the needle round in discrete jumps. No-one makes those today – but John can fix them.

Down again to what was once a tiny Austin 7-sized garage but now holds glass cutting, moulding and bevelling equipment. Small as one speedometer is, it transpires that the processes that go into refurbishing it are many and complex – and John can handle all of them from dismantling, cleaning, and forming a new case through stamping out dial blanks, printing the figures, shaping pointers, to glazing, calibrating and testing the finished unit. He’s a one-man industry. He used to have employees but as they retired he’s been unable to replace them. John’s only support is once a week when Richard Roberts pitches in. “I’m 87 and I’ve been retired for 27 years,” says Richard, smiling. “I came as a temp 18 years ago and here I still am.”

“We had a lady who did one-off artwork with pen and compass and Letraset,” John continues, “but she retired. Now one-offs are hard; a local graphic firm does artwork on computer for me but you need to do 10-plus to be worth it.” Hence the boxes of spare dials which may not be needed for 20 years…

Such laments are frequent in John’s talk: “Chrome platers are disappearing, so are stove enamellers. The little engineering firms who used to do short runs for us have died or been absorbed; now firms want runs of thousands. Even glass has changed; it’s all float glass and slightly contaminated with tin. If it gets damp, acid etches a bloom on it.”

Yet John has so much specialised equipment here it’s surprising he needs anyone else. There are pad and screen printers for dial artwork, templates to let heated glass ‘slump’ to the correct convex shape, ultrasonic cleaners, revolution counter checkers, a water heater so when John has refilled a temperature gauge with alcohol he can calibrate the reading. There are machines to test pressure gauge read-outs, a thread maker for the knurled mounting nuts that locate instruments, a blue buzzing Vibrograf machine that checks clock accuracy, a huge magnetising device: “A lot of instruments use coils and magnets so with this I can saturate the magnets and then wind back to the correct level. That came from the Royal Engineers.”

Teacher with no pupils: John Marks would be happy to pass on his lifetime’s knowledge but has not found any takers

Over decades John has harvested useful materials whenever possible and there are stories behind much of it: “When a speedometer company shut down they were going to skip everything; we filled a van with parts for £100. There were tank speedometers in there we sold for £150. When Smiths Industries closed a factory I rescued a lot of spares, and in the 70s I bought a tea chest full of dials for barrage balloon winches. They were Rolls-Royce speedometers – the military always used top-grade stuff. They are perfect for C- and D-type Jaguars.”

Equipment like this would costs thousands in its time, yet John says he bought most of it for peanuts. The irony is that it’s now invaluable to his operation, but to whom else? Is there a collector or company who can see the value of this unique assemblage?

“I did have one asset stripper came to look, but they said ‘sorry, you’re prehistoric’,” John muses. There are a couple of other instrument restoration firms who could, and presumably will in time, utilise this material, but what about John’s 50 years of learning? Who else could find their way around this rich forest of material? John shrugs: “I’ve had a few young people here to train, but they don’t want to stay in this business. There’s no future.”

It’s a sad situation. Apart from cryogenically preserving John Marks for future downloading, it’s hard to see anyone absorbing a tenth of his knowledge before he finally locks the workshop door and gets some time to himself – interrupted no doubt by pleading phone calls from people restoring Isottas, Hispanos and Marendaz Specials…