What's in a number?

Perhaps it looks like a standard E-type coupé – and it is right now. But it wasn’t always, and after the winter it will look more like its old self. Like an E-type racer, which is how it spent its youth.

In truth this car has always had a tendency to double up, on its jobs, its careers and even its number plate. Sitting outside the BRDC Clubhouse at Silverstone, its deep-red gloss shrugging off the fine smirr of a gloomy day, it’s wearing the number ‘2 BBC’. Which is odd, as nearby is a Land Rover Discovery Sport carrying the same plate. Have we rumbled some nefarious car-cloning scheme?

Here to unscramble the mystery are the car’s latest owner, collector and racer Mark Midgely, and its very first, Robin Sturgess, whose Leicester company has been a Jaguar distributor since the 1940s. He also went racing in the products he was promoting, which is where we came in. For this beautifully restored machine, delivered from the production line to Sturgess in January 1962, was both Robin’s customer demonstrator and his weekend racer. Remember that at this time it wasn’t the norm to modify cars radically for sports and GT racing, although that doesn’t mean that Robin’s prospective customers always knew exactly what was under the bulging bonnet stretching in front of them. It’s the first time he has seen this particular car since a proud customer drove it away from his dealership 55 years ago.

Former life: 2 BBC leads a pack of GT cars in Martini 100 event at Silverstone in 1962 , its last racing season

However, fast as even a standard E-type was, 2 BBC was a step down for Robin.

“I’d raced an XK120 and then in 1958 I bought a C-type, the ex-Mike Salmon, Ecurie Francorchamps car,” he says. “That was a proper racing car.” He nods at the track activity outside the clubhouse: “Used to be able to hire the Club Circuit for testing for £3! I didn’t want to give up the C, but a dealer has to push the current range, not an out-of-date car, so I sold it for £1000. It recently made £5.7m…”

This is actually Robin’s second 2 BBC demo/racer; as coupés were not yet available the first was a roadster which he raced in 1961, including making the first competitive ascent of Shelsley Walsh for an E. His son Chris, who has driven him down from Leicester in the newest 2 BBC, that Discovery, shows me the 1960s stock book with hand-written entries for both cars, as well as two E-types which went to Dick Protheroe, one of their subsidiary dealers and a well-known Jaguar racer. These would in turn become the CUT 7 racers.

Robin retained the 2 BBC number when late in 1961 he ordered the coupé, re-registering the roadster 848 CRY. Some of you will already have twigged about that car’s future fate – crushed by a digger in The Italian Job. Fully restored, that car now belongs to Jaguar expert and author Philip Porter.

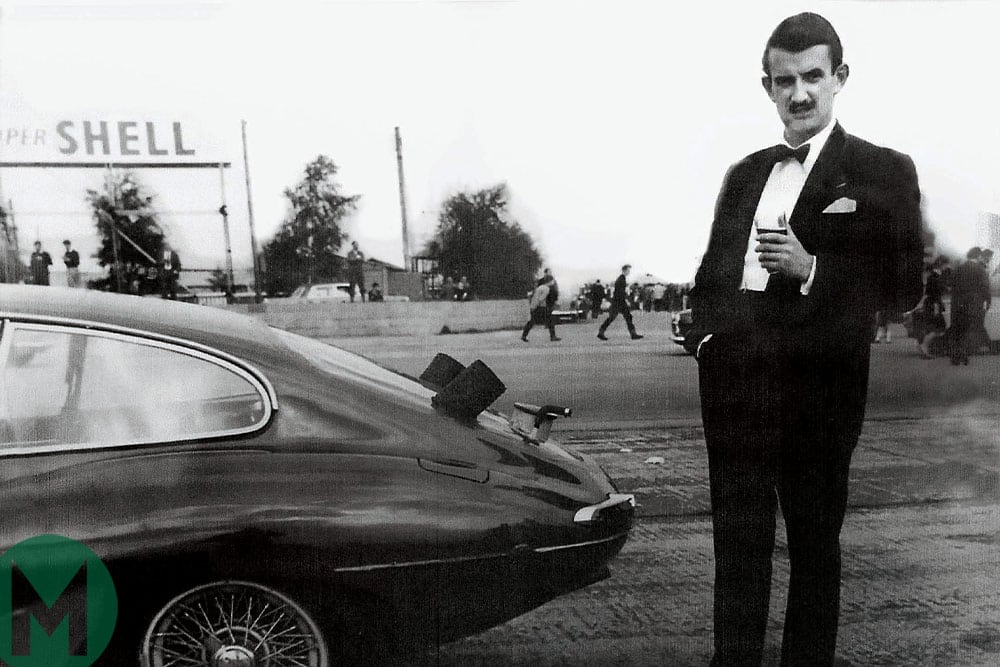

Sturgess in ’62 non- racewear, and reunited with car in favoured race outfit with helmet matched to car colour

NOW 85 and needing a stick to get around, Robin leaves running the firm to his sons Barney and Chris. But he has excellent recall of registering that first roadster: “I tried to get 1 BBC from the local tax office, but they wouldn’t give me it.” He couldn’t know that by 1964 the BBC would have a second TV channel, but he liked the number and has retained it ever since. “I’ve lost count of the number of cars it’s been on,” he smiles. So, it’s just as well the car arrived in a trailer from Duncan Hamilton ROFGO, which brokered the sale, as it’s not road-legal wearing it.

“Lofty England helped with the red car,” Robin continues. “I ordered higher compression, close-ratio gearbox, bigger discs and larger rear wheels, and I had three differentials for different circuits. They hated me in the workshop when I switched from Silverstone ratio to Mallory!” Robin also pitched to Lofty the brave idea of running a SP250, Daimler’s V8 glassfibre sports car, at Le Mans. “I was sure we would finish, but he wasn’t interested.”

While the C-type always travelled on a trailer, Robin drove 2 BBC to all its meetings – and in 1962 there were 22 events, though none very far from Leicester. After all, if he did win on Sunday he had to be back in the showroom to sell on Monday. Thus it was Silverstone, Snetterton, Mallory or Oulton, plus odd sprints and hillclimbs. But while he’s modest about his own efforts – “I was a club racer, nothing more” – he did win on some of those days. Chris gives me a list of that busy season’s results and ‘First Overall’ figures often among the BRSCC and JDC meetings. One of the few entries labelled ‘NIL’ is a BRDC International meet here at Silverstone.

“‘THEY WOULDN’T GIVE ME 1 BBC. NOW I’VE LOST COUNT OF THE NUMBER OF CARS THAT 2 BBC PLATE HAS BEEN ON!”

“That was one of my highlights,” says Robin, despite the outcome (it turns out that ‘NIL’ doesn’t mean DNF, it just means ‘not on the podium’. That’s competitive spirit.). “I’d won three races on the trot and John Eason-Gibson [from the RAC] rang me up and said ‘would you like to drive at Silverstone? We’ll pay you £50!’ Well, that was a bonus. Club racers like me did get free oil and petrol and brakes from the suppliers but starting money was a novelty.”

Although this was still a GT race, Sturgess was suddenly mixing with a different class of driver – including Grand Prix aces. Graham Hill, Jim Clark and Mike Salmon in Aston Martins faced the 250 Ferraris of Mike Parkes and Innes Ireland, while among rival E-types were David Hobbs and Roy Salvadori in John Coombs’ entry. Was this daunting?

“I wasn’t afraid to mix with the big boys, no,” Robin says. “Everyone raced cleanly although they were way ahead. In fact, I’m not sure Graham Hill didn’t lap me.” It was no disgrace that he finished down this field while Mike Parkes took the win – and the Scalextric Trophy! – in his GTO.

The only consistent problem for the Sturgess car, ably maintained by his own workforce, was that perennial E-type weakness, those rear brake discs: mounted either side of the diff they get very hot very quickly on the racetrack. Having wrapped up that year’s Snetterton GT championship, Robin entered for the Autosport 3-hour race at the Norfolk track and although it was at the cool end of September he knew those brakes would overheat if he didn’t take steps. “We fitted a 40-gallon fuel tank and also air scoops underneath feeding air to the discs, with exits through the Perspex rear window we’d installed. It wasn’t enough: the discs were glowing red and the fluid boiled, so I rolled gently into the pits and we tried to bleed them. But the fluid caught fire, and my mechanic Wally squirted a Pyrex on it and gassed himself!”

Extinguisher gas was a real health risk at the time, so after Robin had taken Wally to the First Aid post, he ran back, jumped in the car and set off, praying the brakes had cooled a bit.

“We were in the next pit to Mike Parkes and his GTO,” he recalls. “They had all the kit and I just had these two Welshmen. Anyway, I finished, but a long way back.”

It was becoming obvious at this point that radical modifications would be necessary to keep up with the dedicated teams, and this was supposed to be a customer demonstrator. Until those brake vents arrived Robin was still taking prospects out in it, without mentioning the gas-flowed head and high-lift cams. “It really used to go, even on SU [carbs],but I rather downplayed the performance,” he smiles. “Still, we sold several E-types because of the racing.”

There was another factor why Robin began to wind back the racing after this busy season. “Too many people were being written off. Six of us were at a gathering one year; a year on there were only three of us. My wife didn’t want me to go on racing either.”

Today only big rear wheels hint at racing past, but plastic window, brake vents and big tank, below, will soon return

We know safety wasn’t a priority then, which extended to racewear: “I always raced in plimsolls, salmon trousers tucked into my socks, and green jumper.” Which, barring the plimsolls, is what he is wearing today, and he has brought along his racing helmet from those days, a Herbert Johnson model painted Carmine Red to match the car.

So 2 BBC was retired, the plastic window and brake vents removed, and sold (minus the numberplate, which Robin kept). Robin did race again into 1964 in Formula Libre with a Lotus-Cosworth 22 single-seater, but business and family pressure meant that couldn’t last. With Jaguar, Rover and Singer franchises plus a go-faster accessories operation, things were expanding. What, I ask, was the build quality like on these British mainstays? “Lovely,” he grins. “Lots of expensive repairs!” It wasn’t the end of Jaguar excitement though: for many years Robin has had a Lynx D-type.

THE E-TYPE ITSELF went stateside to live a quiet life, where a client of Hamilton ROFGO noticed it in a private collection. Though it wasn’t for sale he kept asking and finally it returned to the UK last July. New owner Mark Midgley is researching the time overseas: “It disappeared over the horizon for nearly 55 years” he says. Though clearly restored in the last decade or so, the tags and numbers all align, and Mark, who also races HWM 1 and a Shapecraft Lotus 26R, is eager to see it back on the track.

“It will return to Snetterton 3 Hours spec,” he says. “The idea is to sympathetically restore and prepare it to as close to period as possible within the FIA specs, incorporating the Perspex rear window, air-cooling ducts and Le Mans filler as per the period pictures.” It helps that the car retains the close-ratio ’box and big wheels Sturgess fitted. And of course it will, for racing only, wear that 2 BBC number. It would be nice if in a Pre-63 event it found itself against another famous plate, CUT 7. But there’s one period mod that won’t return. “I had a kill switch for the brake lights!” says Robin. “I got away with it. The steward just said ‘We knew you had one, you bugger!”