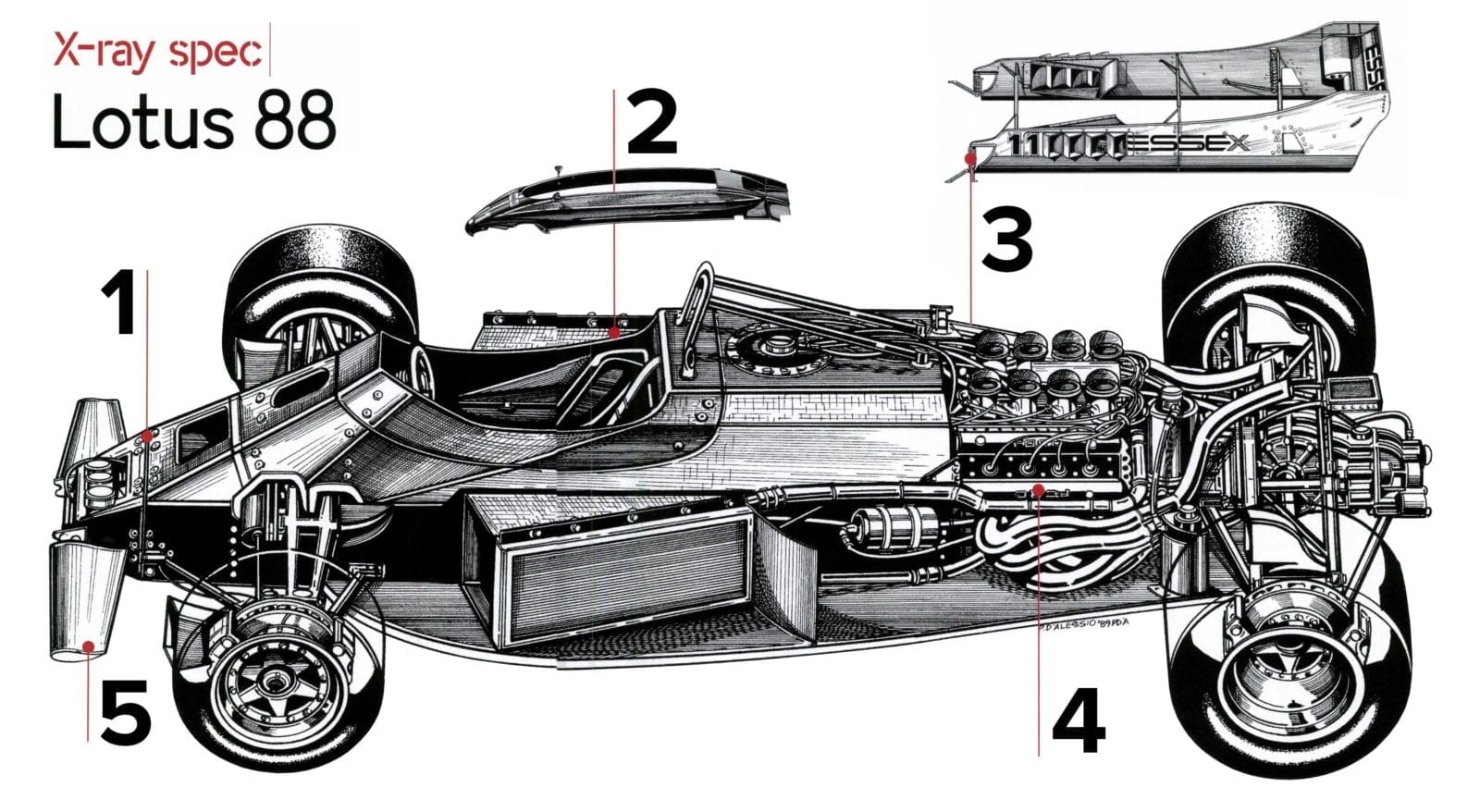

Lotus actually conceived two means of overcoming this. Plan B was active suspension, introduced on the 92 in 1983. Plan A was the 88, which acknowledged the conflicting suspension requirements by incorporating two separate chassis and suspension systems. At its heart was a conventional tub carrying suspension tuned to the needs of the driver. Surrounding this like a gift-wrap box was another chassis that carried the rear wing and the undertray, through which the bulk of the aerodynamic forces would act. This was carried on the wishbones via soft springs that, once the car began to develop significant downforce, would compress on to hard end-stops, lowering the undertray to the optimum height above the track and conveying the aerodynamic forces to where they were needed — the tyres.

As he explains here, Wright remains adamant that the 88 was strictly legal. “The rules banned cars with no suspension, but they hadn’t thought of two suspensions,” he says. “To be honest I think the soft springs were a bit flaky. The rules tried to ban aero forces being fed directly into the unsprung masses, and we were undoubtedly doing that. But if you look at the cars which were allowed for the rest of the year, which dropped down to a lower ride height as they came out of the pits, I don’t think the 88 was any more illegal than those.” But the other teams, scared that Chapman had moved the goalposts once again, connived in its downfall. A complex but practicable design solution was lost, and so too was F1 ‘s foremost original thinker.

Lotus 88: The road to inspiration

By Peter Wright

“The 88 came about when I was thinking of how to apply ground-effect to road cars, where there aren’t any rules. I came up with an undertray hinged on either side of a central keel and fixed at the outer ends to the bottom wishbones. This way you could keep a consistent gap to the road. Chapman sent Martin Ogilvie and I upstairs to design a racing car based on this approach. We came up with the 86, which used the aluminium tub from the 81. We built a carbon-fibre and Nomex honeycomb body around this, with skirts, and in testing it showed a lot of promise. When FISA banned skirts, we realised that we had the solution to the new rules. Chapman being Chapman got terribly excited, and off we went.”

1

“Martin Ogilvie and I were testing how stiff the honeycomb was when it broke the inner skin failed and it folded up.” says Wright. “Martin suggested we build the monocoque like that — cut the inner skin, fold it, put a bandage inside and we had a wonderful corner joint. The carbon monocoque was built out of a large, flat sheet. Chapman said the only truly flat thing you can buy is plate glass, and ordered some, but we didn’t have a good release agent and we had to chip the early mouldings off. We got through a few sheets of glass before we found a suitable release agent. We found that crash strength was similar to an aluminium structure, but were worried about the carbon turning to powder, which is why we came up with the woven-in Kevlar although I don’t think it contributed much.”

2

“The first monocoque wasn’t really stiff enough around the cockpit area, so a structural engineer who worked with Chapman on the boats was hauled in to fix it. He put a heavy cuff around the cockpit aperture. and we also put diagonal wraps around it. These made a big difference. McLaren’s solution was more elegant but of course they didn’t make it — Hercules did it in the US — and it took much longer. Ours took four months from concept to first monocoque. And with it being a hand layup, it was cheap and you could easily modify it. Those monocoques are still going strong, being raced by Classic Team Lotus. They were very robust.”

3

“We realised that the first chassis’s suspension needed something with a large offset and a very low rate, so we used gas struts. Once you overcame the preload only a little more speed was needed to use up all the travel. Most of the initial tests involved standing out by hairpins to see if the outer chassis would come up on slow corners. To prevent this we put in very high rebound damping so that it would come down quite easily but take a long time to rise up again. The idea was that it would stay up to the end of the pit road but remain down through the slowest hairpins. Whether we achieved that or not I wouldn’t like to say because we didn’t test it at enough places.”

4

“Cosworth did us a special engine for the 88, relocating some of the pumps down the side. We needed the space because we had a body that was floating around the engine. It was probably the first time an engine had been designed for aerodynamic requirements, so it was the beginning of a trend. When we tested it originally at Jarama in the 86 we had such copious oil leaks that the mechanics called the car the Torrey Canyon, but that was fixed. Chapman would have had to persuade Keith Duckworth to make the changes, so I expect Keith knew all about the car’s design.”

5

“The only aerodynamic element attached to the second, inner, chassis was the front wings. There was an awful lot of front downforce from the body so the front wings were more trim devices than anything. The forces they generated were quite small and they didn’t interact particularly strongly with the ground, so it was acceptable to put them there.”