The 1958 Argentine Racing Season: Grand Prix, 1,000km & Formule Libre

Stirling Moss wins the 1958 Argentine Grand Prix, while Ferrari dominates in sports cars

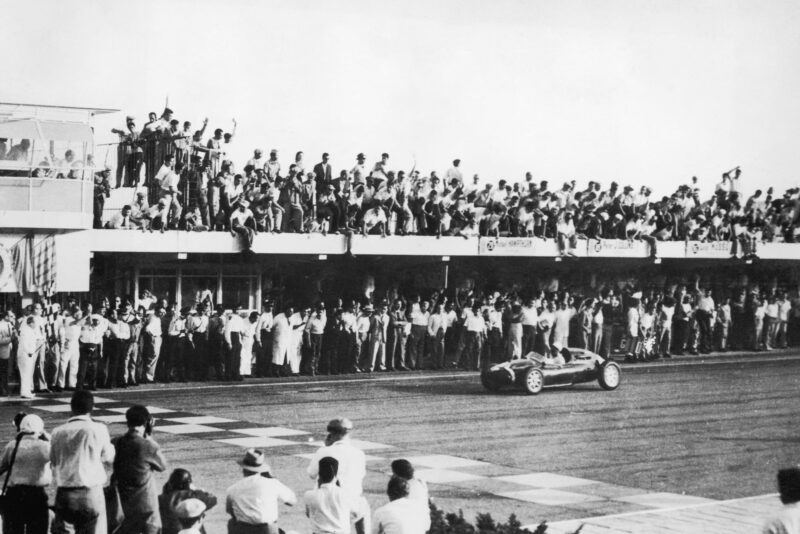

Crowds cheer the victorious Moss

Getty Images

1958 Formula 1 Argentine Grand Prix

At first it looked as though the Italian teams had stolen a march on the British Grand Prix teams, by being ready for the 1958 season and getting to the Argentine in time for the first round of the World Championship. Both Ferrari and Maserati cars took part in the Argentine Grand Prix, while Vanwall and B.R.M. did not, and only a lone Cooper-Climax represented Britain, but, in actual fact, there was only one new car in the brief entry of 10 machines that took part in the race, this being one of the Ferrari entries, the other nine cars all being 1957 machines.

Collins and Musso drove the two V6-cylinder Ferraris that ran at Modena and Casablanca last year, while Hawthorn had the new one; though new in construction it was not new in design, being as the other two, with large-tube ladder-type frame with small-tube superstructure, the new design of chassis not being completed in time for this race. Among numerous small modifications made to the cars since Casablanca, Hawthorn’s model had experimental brakes, which proved to be too powerful, causing frequent wheel-locking, and an aero-screen in place of the normal wrap-round Perspex one. The three lightweight chassis Maserati cars used by the factory team in 1957 had new owners, two of them being bought by Fangio’s Scuderia Sudamericana, and the third by the Australian racing motor-cyclist, Ken Kavannagh. The other three Maseratis in the race were the old ones of Godia and Gould, and a similar old one borrowed by Schell. As Behra was without a car, Kavannagh lent him his car, and delayed his motor-racing debut for a couple of weeks, rather than see a potential winner standing on the track-side. To complete the field of ten there was the R. R. C. Walker Cooper, driven during last season by Brabham; this car being a slightly stronger version of the Formula II chassis, with various modifications to suspension and cockpit cooling, and fitted with a 1,960-c.c. Coventry-Climax engine. With no proper Grand Prix car at his disposal, Moss agreed to drive the little Cooper, and it was rushed to the Argentine at the last moment, the Italian cars having gone from Genoa in mid-December.

Fangio and Menditeguy drove the Sudamericana cars, the World Champion taking his choice after trying both of them, and, apart from alterations to compression-ratios and carburation to suit the straight 130 octane petrol, they were virtually as raced last season by the factory. In spite of the change of fuel, practice lap times were as fast as last year and there was little to choose between Maserati and Ferrari by the time practice had finished, less than one second covering the first five, who were Fangio, Collins, Hawthorn, Behra and Musso.

For a change the weather was reasonably cool for the race on January 19th, and all ten competitors came to the line, but only nine got away for Collins broke a drive-shaft as he let the clutch in. Although Hawthorn led at the start the Ferrari was not happy, for it had too much understeer for the comparatively slow Buenos Aires Autodrome circuit, with its sharp corners, and it was not long before Fangio took his Maserati into the lead and Behra harried Hawthorn. After a slow start in the little Cooper, Moss began to drive really hard and caught Behra and Hawthorn, while Musso in the other Ferrari was only just managing to keep up. Menditeguy spun on lap three and dropped back with Schell, Godia and Gould, the also-rans. After only 30 of the 80 laps had been run Hawthorn’s car was losing its oil pressure, so he stopped to see if the level was low, but it was not so he carried on and hoped the engine would not blow-up. After a record lap, on 130 octane be it noted, Fangio lost a tyre tread and stopped for a new pair of rear wheels, and this dropped him from the lead with a 16-sec. advantage over Moss, who was in second place, to fourth place. Moss was now leading and by half-distance was 53 sec. ahead of Fangio, whose Maserati was showing signs of tiring, as was Behra’s car, for though they would appear to go very fast on straight petrol there was a certain amount of overheating, which is not surprising remembering the cooling qualities of alcohol, and that they were originally designed as alcohol engines, while the V6 Ferrari engine and the Climax engine were designed specifically for petrol.

Moss’s tyres last to take victory in Buenos Aires

Getty Images

With his fingers crossed and not looking at the oil-pressure gauge, Hawthorn began to make up for his time lost at the pits, but, though he caught and passed Behra and Fangio, he could not quite catch Musso. With the tyres of the Cooper wearing pretty thin Moss eased his pace very considerably, for a pit-stop was out of the question, having bolt-on wheels. Musso was not aware that the Cooper tyres were only just going to last out and made no serious attempt to press Moss, a fact indicated by Hawthorn lapping a lot faster than Musso, though too far back to be a menace to Moss. Even though this little Cooper, with canvas showing on both rear wheels, was in the sights of the Ferrari, Musso seemed more content with a certain second place than having-a-go for first place, so that Moss ran out the winner of the 1958 Argentine Grand Prix, which the new F.I.A. regulations luckily permitted to be reduced from 100 laps to 80 laps, 300 kilometres of racing being considered long enough for a Grand Prix in these “milk-and-water” days of motor racing.

1958 Argentine 1,000-kilometre Sports Car Race

The following Sunday, January 26th, the Argentine 1,000-kilometre Sports-Car Race took place, to the new F.I.A. Formula limiting such events to cars of a maximum of 3-litres capacity. The entry was very mediocre, the only serious factory contenders being the Ferrari team, with three new V12 Testa Rossa cars, all with the new 2,953-c.c. engine based on the Europa model and four-speed gearbox in unit with the engine. Two of the cars had de Dion rear axles, the third being an experimental car with a normal rigid one-piece rear axle. Collins and Hill were in one de Dion car, and Hawthorn and von Trips in the other, the third Scuderia Ferrari car being taken by Musso and Gendebien. More by way of making some interest to the race than a serious rival to the Maranello cars, Fangio entered with Godia in the Spaniard’s 300S Maserati, and Moss and Behra had a similar car, from the Sudamericana stable; this, unfortunately, broke rather severely in practice, but the Porsche team came to the rescue and lent them the works Spyder with enlarged 1,585-c.c. engine. For the rest, the entry was a motley collection, making up 28 cars, including Trintignant/Picard (Ferrari Europa), Barth/Mieres (factory Spyder Porsche 1500), de Tomaso/Miss Haskell (Osca 1500), and two production Testa Rossa Ferrari 3-litres, one owned by the American Ferrari agent von Neumann, the other by a Venezuelan driver, Drogo.

The event was an obvious Ferrari benefit, in which they should have finished 1-2-3, but Musso spoilt their chances on the opening lap by crashing his car. As a result his co-driver Gendebien partnered with von Trips, as Hawthorn was suffering from sunburnt legs and preferred not to drive unless absolutely necessary. Fangio realised he had little hope of challenging the Ferrari team, for even if he could have kept the 3-litre Maserati with his rivals, it was unlikely that Godia would have been able to maintain the pace. In consequence he “played bears” in an attempt to enliven the opening laps, and spun off on a corner and wrote off the front end of the Maserati in a most impressive manner. There was no opposition whatsoever to the two new Ferraris and their pit-stops and driver changes were very leisurely, oil being poured from tins, for example, and a rather monotonous race slowly ticked off the hours. It so happens that the speed of the race was not all that slow, and, by reason of the new 3-litre being a first-class car, Hill was able to set up a fastest lap that was also a record for the circuit, beating that made by Collins in 1956 with a 4.9-litre Ferrari. On paper, the new F.I.A. rules were vindicated, as in the Grand Prix, for the 3-litre Ferraris were more than fast enough.

A maximum time limit was put on the period a driver could spend at the wheel and, due to miscalculations, the Ferrari team had to be shuffled around just before the end of the race, and this allowed the Porsche of Moss/Behra, which was being driven pretty hard and going splendidly for a small-engined car, to get on to the same lap as the leaders, so that the two works Ferraris and the Porsche finished comparatively close in a rather uninspiring race.

1958 Formule Libre Buenos Aires Grand Prix

To complete the Argentine season a Formule Libre event was held on February 2nd, on a slightly slower circuit in the Autodrome, and was called the Buenos Aires Grand Prix. The Ferrari team had by this time received a fourth car, this being a brand new one with small-diameter tubing space frame, no fuel tank in the cockpit, but a large tail tank running right up into the headrest. The V6 engine, like those in the other three cars, had a large double-bodied 12-cylinder magneto mounted on the rear of the left-hand inlet camshaft. The other three cars were those used in the Argentine Grand Prix, Hawthorn’s model having the standard brakes refitted. The race was run in two 30-lap Heats, the addition of times giving the final classification, and with Collins, Hawthorn and Musso as the main strength of the team, the new car was to be driven by von Trips in Heat 1 and Phil Hill in Heat 2, in order to give them both some Grand Prix practice. Fangio and Menditeguy were in the same pair of lightweight Maseratis, and Kavannagh had his car back for this race, though it was not very fit as some parts had been “borrowed” to make one or the Sudamericana cars more healthy. The Scuderia Centro-Sud had their two old cars running and, rather than be a spectator, Behra drove one, while Roberto Mieres drove the other. Bonnier was in the process of buying Godia’s Maserati, so the Spaniard was to drive it in Heat 1 and the Swede in Heat 2. Gould was still with his own car, and Gonzalez, the well-known Argentinian, as distinct from the not-so-well-known Gonzalez from Venezuela, drove his Ferrari 625 fitted with a Chevrolet V8 engine. Moss was again in the Rob Walker Cooper and the rest of the field was made up from South Americans with Yankeee-engined “hotrods.”

The start was due at 4 p.m. and at the time it was raining, but, with all the cars on the grid. Behra and Menditeguy had not arrived. It appeared that they thought the start was at 4.30 p.m., so there was a certain amount of pandemonium with two cars being driverless. Practically as the flag was falling, Godia was put into Menditeguy’s car, Bonnier into Godia’s, and Scarlatti was found in the pits and popped into Behra’s car, and everyone rushed off to the first corner. One of the ” hot-rodders,” with more steam than brakes, clouted the little Cooper and sent it flying off the circuit, rather bent and out of the race, and Collins once again broke a drive-shaft as he left the line. This was Hawthorn’s day and he got away in the lead, followed by Fangio, who had a 3-litre engine in his car, and von Trips and Musso. Hawthorn was in fine form and simply ran away with the Heat, finishing well ahead of Fangio, while Musso came home in third place. After the start Behra and Menditeguy arrived and there was a great deal of flagging-in and cars being given hank to their rightful drivers. Although driving an old Maserati, Behra really enjoyed himself and finished fourth. Kavannagh did only a few laps in his first Grand Prix for his car was not really in first-class condition, and von Trips had a spectacular crash while going down a straight, the new light Ferrari being a bit “twitchy” in the wet and spinning off. It was very badly wrecked and the German driver was lucky to get away unhurt, but it meant that Hill did not get a drive in Heat 2.

The first Heat grid positions had been decided on practice times and Heat 2 was in the order of finishing Heat 1, so that Hawthorn was well placed and all he had to do was to sit on Fangio’s tail and he was a certain winner of the overall event. After Collins’ two broken drive-shafts, Hawthorn left the start very gently, but it was not gently enough and one of his broke, putting him out of the race. The reason for all these breakages was that they were originally designed for Formula II, with only 150 b.h.p. going through them, and the safety factor was not great enough for 260 b.h.p. Clearly, there will be a lot of splined-shaft manufacturing going on at Maranello before the next Grand Prix. With Hawthorn out and Collins and Musso spectators from Heat 1, Fangio had no opposition and won Heat 2 comfortably, which gave him the General Classification. Ferrari hopes were left with Musso, but he could not keep Menditeguy at bay, and for once the wild Argentinian sportsman did not spin, and finished second in Heat 2.

This final event had been a very muddled one, but at least it left the three competing makes with a victory each: Cooper in the Argentine G.P., Ferrari in the sports-car race and Maserati in the Buenos Aires G.P.; so they should have all returned to Europe equally contented.