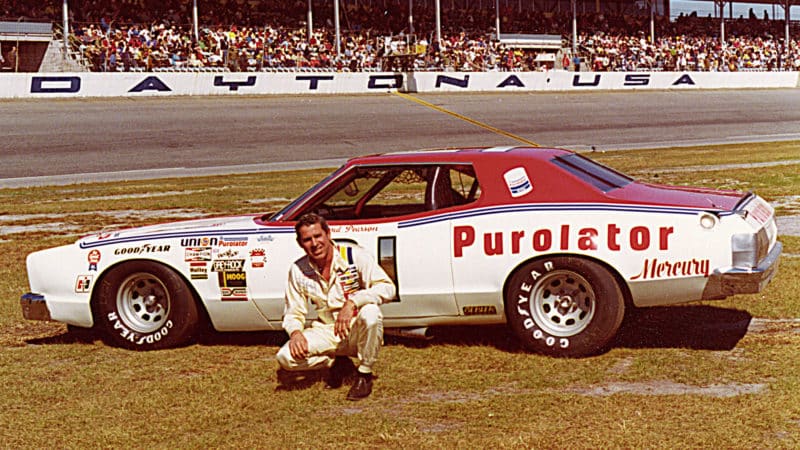

The following Monday afternoon I sat in the press box above the steaming black asphalt cauldron of Darlington Raceway and waited for the ‘Silver Fox’ to claim his inevitable crown. In the post-race interview, Pearson stood at the press box window with the ‘Old Lady in Black’ – as the treacherous ribbon of asphalt was known – for a backdrop. The broad white teeth and the creamy Purolator driving suit stood in sharp contrast to a face burned red by driving into the late afternoon sun. Again, the charisma was palpable as Pearson discussed, laughed and cut up while responding to questions from writers about one of the most accomplished stock car seasons on record. It was clear that winning suited him.

By the time the 1976 season had ended, Pearson had won 10 races in 22 starts. It was the second time in four seasons that the candy apple red-and-white Wood Brothers Mercury had blown away fields seemingly at will. But this season was special because of Pearson’s victory over Petty at Daytona, in what many regard as the greatest finish, if not race, in NASCAR history (see panel).

Once the chequered flag had fallen on that much discussed ‘500’, it was Pearson who made his way to the press box afterward to tell his side of the victory. But as usual, he took the quiet and subtle route despite the tumultuous ending to the race, saying that Petty had apologised to him after their wreck just 400 yards from the finish line and that he would be happy to “run beside him at high speed any time.” Pearson never did say just what caused the famous crash, only implying that Petty’s apology was explanation enough.

The reporters that day – I had yet to land my job covering the races – learned once again what I would learn later that year in Darlington: Pearson would talk a fair amount, but rarely say much that was quotable. He never did like to address controversial issues either, or questions regarding how he won so many darn races, or anything that might make him seem egotistical. He was far too proud, and too private, to have his ego paraded through newspapers by his own voice.

Pearson and Petty (right) managed to keeps things cordial off-track, even if it was sometimes less so on the black stuff

NASCAR

On the track, Pearson’s driving style was similarly quotidian. His lines were consistent, smooth, uninterrupted arcs. His tactics were to hold his cards until the final miles when a race and the money — were on the line. If not for his fame and the familiar 21 writ in gold on his car, one might have felt like Pearson came out of nowhere to win races. This was particularly tile year in, year out at Darlington, where he earned his reputation on a notorious wrecking yard of a crooked oval by winning 10 times.

This same immaculate driving style meant Pearson earned what remains a record 64 poles on superspeedways, or tracks one mile or longer. He holds another record unlikely to be broken for most consecutive poles at one track, having earned 11 straight at the Charlotte Motor Speedway and 14 all together. But perhaps it is an unofficial record that speaks most about Pearson’s ability to concentrate behind the wheel: in 574 career starts in NASCAR’s premier division, not once was he injured seriously enough to require a trip to hospital.

This skill at avoiding accidents or confrontations on the track, as well as controversy off it, sustained Pearson over the course of what is one of the most remarkable careers in NASCAR history. Intensely proud and private, the small-town South Carolinian’s lack of lust for the limelight means that he is often overlooked as perhaps the greatest driver in the sport’s history.