1970 United States Grand Prix race report

Fittipaldi took his debut win driving for Lotus at Watkins Glen

Motorsport Images

Lotus come-back

Watkins Glen, USA October 4th

Transport from Canada for 24 of the 26 Formula One cars which had been seen at St. Jovite was provided by communal trucks, making quite a change from the gaily-painted transporters in which they are normally carried in Europe. The Ferraris, as always, came on their own lorry, but the 26 arrived safely in the pleasant town of Watkins Glen, situated in the colourful Finger Lakes region of New York State, where the Grand Prix of the United States has now firmly made its home. The race was the tenth in the series to be held at Watkins Glen.

All the teams except the Ferraris were to be housed in the Kendall Tech Center, protected by security guards from the crush of eager Americans anxious to make the most of their only opportunity to see Formula One cars on US territory. Attendances at Watkins Glen have risen steadily over the past decade and this year it reached 100,000 for the first time ever, though this included “hangers-on” such as guests and the press. American track safety regulations and the fact that the crowds tend to come early and camp within the grounds of the circuit present quite a task for the local officials, who cope firmly but fairly without having to resort too often to the help of the unpopular police. Those drivers who had raced in Canada were all due to take part in the Grand Prix, with the addition of several more. The most important additions to the race were the two Lotus 72s of Gold Leaf Team Lotus, returning to the scene after a one-race respite to rally and recover from the sad events at Monza. They brought 72C/R5 for the young Brazilian Emerson Fittipaldi, this now repaired after the practice accident at Monza (its first appearance), plus 72C/R3, the car which has until now been driven by John Miles. Having asked for time to reconsider his position with the team, however, Miles found himself without the drive and in his place was the 29-year-old Swede Reine Wisell. It appears that WiseII will be Fittipaldi’s regular team-mate in future, so the slogan “Gold Leaf Team Lotus, racing for Britain”, which is emblazoned on the side of the Lotus transporter, may well have to be reconsidered.

Other cars brought out direct from Europe were the second Surtees, TS7/002, this being entrusted to Derek Bell, the Formula Two expert who has just finished a long spell on the Le Mans film. It was Bell’s second Grande Epreuve of the year and keeping an eye on him was Tom Wheatcroft, who had loaned one of his two Coswprth engines to the Surtees team for the race. Bringing McLaren numbers up to four was Bonnier in M7C/1, last seen unsuccessfully trying to qualify at Monza and now painted yellow with a white and red stripe. Nevertheless, it was showing its age, this being certainly the hardest used car in the field, having served Hulme throughout the 1968 and 1969 Grand Prix seasons. Two more cars were brought from distant parts of the United States, Volkswagen dealer Pete Lovely bringing his familiar Lotus 49/R11, all the way from Seattle, Washington. This car is still in 1969 49B trim with 15 in. front wheels. The other American was the Texan Formula A driver Gus Hutchison, making his Formula One debut in the 1968 Brabham BT26 which lckx had used early in 1968. The car is eligible for Formula A racing but Hutchison had not used it as such since July, claiming that is it not as fast as the 5-litre Lola T192-Chevrolet which he is now racing in Formula A.

Also making a start in Formula One was twice British hill-climb champion Peter Westbury, who races his own Brabham in Formula Two, assisting the GPDA with matters of circuit security in this sphere: he had been asked to drive the fourth BRM, using 153/04 while Oliver switched to the “spare” 153/06. The latest BRM engine was not in use; it was removed from the newest car before practice and kept in reserve.

These newcomers swelled the number of drivers to 27, three of whom would be disappointed, for the regulations stated quite clearly that 24 cars only would start. The prize money system pioneered by Watkins Glen brought the total purse to just over a quarter of a million dollars (about £100,000), the winner taking $50,000 and the 24th man £6,000, even if his car expired within inches of leaving the starting line. Under this typically American system the drivers were going to have to work hard for their money and the pressure was naturally on the mechanics to make sure that their cars were in tip-top condition to guarantee a finish.

The mechanics all concentrated on general preparation unless engine failure in Canada dictated a change, for as always, they were waiting until after first practice to install the engines which were to be used for the race. On that evening, no fewer than 14 engines were being changed, 13 of them in the Tech Center at the circuit and the remaining one (the flat-12 in Ickx’s 312B/001) at the Chevrolet agent’s garage where the Ferraris are traditionally housed.

Qualifying

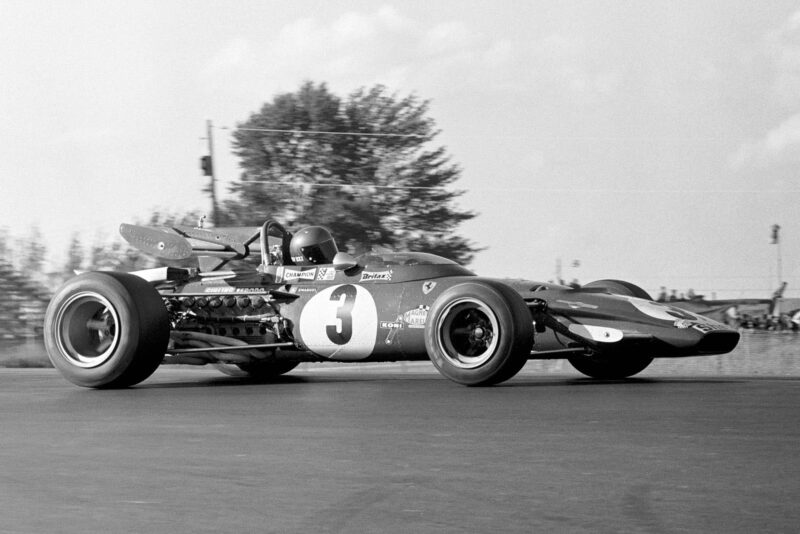

Jacky Ickx

Motorsport Images

First practice on Friday took place between 1 and 5 p.m. in dry and slightly cold conditions. Many of the newcomers to Watkins Glen were surprised to find that a country as vast and wealthy as the USA should have one of the shortest Grand Prix circuits, and several commented also on the narrowness of the track. About half of the surface had been repaired after the catastrophe which struck Watkins Glen during the Manufacturers’ Championship/Can-Am weekend in July, but the circuit was still somewhat bumpy and some of the fresh tarmac very slippery. It rapidly became apparent that although Jochen Rindt’s existing F1 lap record of 1 min. 04.34 sec. was attainable, it would only be a few, if any, who equalled his fastest practice lap in 1969 of 1 min. 03.62 sec. and that Bruce McLaren’s Can-Am qualifying fastest lap (set in 1969) of I min. 02.21 sec. was quite out of reach, even for the latest and most sophisticated of Europe’s single-seaters. With their considerably greater horse-power, the Can-Am cars have an appreciable advantage around Watkins Glen, which is deceptively fast and has a lap speed of over 130 m.p.h. for anyone who can break the I min. 03.6 sec. barrier. Speeds such as this mean that the 2.3-mile track is always full of cars: there are plans not only to widen it but also to extend it within the next twelve months. the money being provided out of the proceeds of the racing by the Watkins Glen Grand Prix Corporation. This organisation, entirely non-profit-making, has always organised the Grand Prix along firm but congenial lines and the tradition was continued this year under the guiding hand of its new Executive President, Mal Currie. One of the first tasks faced this year by Currie was a deputation from the drivers to have removed a rather high kerb on the outside of the slow corner which brings the drivers in front of the pits. Earth-moving machines were at work complying with this request on the morning of first practice. Currie, however, was not so compliant with another request, this being that all 27 drivers should be allowed to start.

Ickx left the others floundering on the first day of practice, gradually reducing his times as he tried some new Firestone tyres, until with an hour to go he was the only driver actually to get under Rindt’s official lap record from 1969. There was more to come from the Ferrari and Ickx, but for the moment his time of 1 min. 03.4 sec. was almost a second faster than that set by Stewart, who had been delayed from using the Tyrrell because there were some alterations to be made to the car as the result of fitting some new front uprights, sent out from England in connection with the new front hubs to replace the components which had cost Stewart the race in Canada.

Stewart, too, was trying some different tyres, in this case some front Dunlops with a very low profile construction. Unlike Ickx’s Firestones, they were not a complete success, largely because both the Tyrrell (and the BRMs, which were also trying them) bottomed on certain parts of the course. Stewart also tried his usual March, setting a time in the early part of the session which would comfortably have qualified him in the top ten, but as soon as the Tyrrell was ready he concentrated on that and hardly bothered with the March. Nevertheless, Amon seemed happy enough with his STP-March, being overall third fastest at 1 min. 04.28 sec., faster for once than Regazzoni’s Ferrari (1 min. 04.3 sec.). Others to set good times were Fittipaldi 1 min. 04.69 sec.) and Hill (1 min. 04.81 sec.), which indicated that the combination of low frontal area and good traction offered by the Lotus 72C would again be of considerable assistance. This was in fact one of Hill’s better performances of the year and during the race he was to show that his happy memories (wins in three consecutive years) outweighed the recollection of the accident during the 1969 race, when he had suffered extensive leg injuries after being thrown from his crashing Lotus 49B.

It was significant that at this stage Firestone-equipped cars filled five of the top seven places, Dunlop claiming the remaining two, and Goodyear users did not appear until the last three places in the top ten.

At the bottom of the list one noted the names of Bonnier and Westbury faster than Siffert and Beltoise, both of whom had failing engines, and de Adamich right at the bottom of the list following another Alfa Romeo engine disaster.

Before very much of Saturday’s practice had gone by, the skies suddenly blackened and there was a cold drenching rainstorm which brought all activity to a complete halt. When it resumed there were still two hours of practice remaining, but the track, though well drained, seemed reluctant to dry out and everyone was soon sloshing round with rain tyres fitted. Had practice not been extended because of a slightly late start, it seems that all grid times would have been taken from the first day’s times, but in the final quarter-hour some excellent speeds were announced and the practice became very exciting indeed. Nevertheless, Ickx’s time was still the best, despite last-minute efforts from Stewart. The Lotus pit thought that Fittipaldi had beaten Stewart for the second-best place on the front row of the grid, but when the times were announced it was revealed that the youthful Brazilian was a mere five-hundredths of a second slower than the Scot, timed by the complex electronic system. Fittipaldi was the third and last driver to break the 1 min. 04.0 sec. barrier, being permitted by Chapman to do over 220 practice laps, more than twice the race distance, in two days!

Only three drivers managed to crack the 1 min. 04.0 sec. barrier, but indicating the closeness of present Formula One cars and drivers was the fact that during the final hectic 15 minutes of practice when the track was very nearly dry, no fewer than eight drivers set times under I min. 05.0 sec. and a further eight did sub-I min. 06.0 sec. times. Neither of the two Brabhams figured very high on the grid, something of an embarrassment to the British artist who had done an accurate and very attractive painting for the cover of the programme suggesting that Jack Brabham would be leading the race. In fact both Brabhams were out of the hunt, partly because of their tyres but also because the steering was tending to seize on full bump. The problem had first manifested itself at St. Jovite and both cars were fitted with new front lower wishbones (one of which had broken when Brabham was testing Stommelen’s car in Canada) without solving it.

Schenken was a very envious spectator as the two works Lotuses practised almost endlessly: there was only one Cosworth engine for the De Tomaso and his training had to be strictly limited. Nevertheless, his time set on Friday was better than Gethin’s McLaren achieved. The three last qualifiers on the grid were Hutchison in his space-frame Brabham, one hundredth of a second faster than Siffert, who was once again in fuel feed trouble before his smoky engine lost its oil pressure, and Bonnier, who scraped in mainly because Westbury, Lovely and de Adamich had problems which could not be cured in time for those essential last few moments of practice.

Westbury’s engine blew up after it had been over-revved while the driver was getting accustomed to the unfamiliarly long gear-change movements of the BRM, Lovely’s gearbox parted company with the bell-housing (breaking a drive-shaft as it did so) and de Adamich had another bout of his familiar ill-luck, first when the new engine failed on Friday, then on Saturday when an oil line came detached and later in the day a small electrical fire broke out. It was the opinion of many drivers (members of the GPDA and otherwise) that Bonnier would have done much better to stay in Europe with his 2-litre Lola sports car. He must have felt better able to face his fellows having qualified, for later in the afternoon he conducted a GPDA meeting in a room provided in the Tech Center: unfortunately the whole of one wall consisted of a window, through which the Americans “rubber-necked” quite shamelessly. An interesting point which emerged during the weekend was that neither Regazzoni nor Fittipaldi had yet been invited to “join the club” even though it contains some people who are far less likely ever to win a Grande Epreuve.

Race

Fittipaldi leads the field

Motorsport Images

It rained again overnight, but a stiff wind late in the morning swept the showers away. When it abated there was a big black cloud hovering over the circuit and there was the rare sight of mechanics scurrying around with rain tyres and preparing to fit them on the grid. Had the race been started on time, no doubt several people would have made the gamble, later to regret it. In fact the sky was clearing rapidly, so almost everyone started their warm-up laps on dry tyres, the sole exceptions being Regazzoni and Bell, who set off on intermediate Firestone tyres. When the flag dropped, the race was 20 minutes late.

The start was clean, Stewart seizing the lead from Rodriguez, but Fittipaldi made a very poor getaway, ruining the advantage of his excellent practice time, and by the time they started the second lap the Lotus was down in eighth place immediately behind Oliver, who was tailing the TS7 of Surtees, Amon and the two Ferraris., lckx lying third ahead of Regazzoni. After only five laps, Fittipaldi was up to seventh, Surtees becoming the first to make a stop, a permanent one, with a loose flywheel. Oliver passed Amon on lap 12 and although Fittipaldi maintained station behind the March he didn’t threaten to pass. It seemed that Stewart’s apparent lack of practice speed was merely a smoke screen, or possibly it’s because the Tyrrell is much more manageable than anything else when its tanks are full, for as in Canada he was simply streaking away. Rodriguez’s grip on second place was prised open by Ickx after 16 laps and one lap later the Mexican had to let Regazzoni through, but there was no doubt that the combination of Stewart and Tyrrell-Cosworth was as irresistible as that of Rindt and Lotus 72 had been at Zandvoort.

Hill was not far behind Fittipaldi, tailed by IHulme, Wisell and Bell. Pescarolo was holding up Brabham (again!), then came Peterson, shortly to be passed by Siffert, next a lowly-placed Beltoise, Cevert, ahead of a trio comprising Gethin, Stommelen and Schenken. Eaton’s BRM engine expired after 11 laps (when the Canadian had just overtaken Peterson), so the remaining runners were Hutchison and Bonnier. The American completed 14 laps before pulling out with a loose petrol tank, but Bonnier made a series of stops and restarts, once again earning some unfavourable comments from his fellow drivers. Oliver joined Eaton in retirement, for the same reason, a broken engine, on lap 15.

Frank Williams’ Schenken retired at half distance with suspension failure

Motorsport Images

A large faction of Ferrari supporters had greeted Ickx’s move into second place with cheers, but when they groaned on lap 37 it was for Regazzoni. The Swiss made an initial stop to have a tyre replaced and quickly followed it up with two more, the first to replace the Dinoplex “black box” part of the ignition system and later to have parts of the exhaust system removed. The first stop moved Amon into fourth place behind Rodriguez’s BRM and elevated Fittipaldi into fifth. Shortly before half-distance Amon (like Regazzoni) came into the pits to have a worn-out front tyre replaced, dropping the leading March well back. ‘Wisell was now lying behind Fittipaldi, Hill having made a stop to have a fuel leak repaired. The cockpit of the Lotus was awash with fuel, so Rob Walker arranged for John Surtees to change clothing in the pits with Hill. The sight of two former World Champions stripping stark naked (Hill insisted on underwear as well as coveralls) relieved to some extent the two drivers’ misfortunes. Hill continued in the race for more than 30 laps before his Lotus halted out on the circuit with a broken clutch.

At half distance, 54 laps, Stewart was almost half a lap ahead of Ickx with Rodriguez third and Fittipaldi about to be lapped. Three laps after the Tyrrell had swept past the Brazilian’s Lotus, Fittipaldi found that he was third, for Ickx’s Ferrari had started to leak fuel out of a union on the outside of the car, losing ten places while it was repaired at the pits. Wisell was no longer troubled by Bell for fourth place, Hulme was dropping back with a sickening engine and Amon was next. His team-mate Siffert had made a stop to complain of a similar tyre problem, restarting after a new one had been fitted. Brabham had spun, backwards, to a halt directly in front of the pits on lap 32, his gearbox not working properly: although it was a strictly irregular move, his mechanics administered help on the circuit, beyond the protection of the pit rail, and he resumed even farther down the field than before. Schenken had got the better of Stommelen and Gethin for a brief period before a weld broke in the rear subframe and he had to retire.

Sixty laps passed with Stewart leading handsomely, then 70. At 76, though, there was plainly something wrong with the dark blue Tyrrell for although it sounded healthy enough one bank of cylinders was smoking heavily. A plastic “tie-wrap” securing an oil line had melted from the heat of the exhaust and the rubber itself had burned through on a hot exhaust pipe. Tyrrell thought that a piston might have broken up and put out a signal to Stewart to switch on the pump which returns oil from the catch tank to the dry-sump tank, but the situation did not improve and after 82 laps of leading the race without any sort of challenge, Stewart had to stop on the circuit with no oil remaining for lubrication, much of it being on the track. It was the last of the Tyrrell challenge, for Cevert had left the race in a distinctly exciting manner when a rear wheel fell off, the result of a hub failure. Early in the race he had made one stop to have the hub on the other side replaced! While Stewart slowed, Fittipaldi and Wisell had been able to unlap themselves. The two Lotus 72s lay a threatening second and third behind Rodriguez’s sole remaining BRM, but were themselves safe from any pressure which might be offered by Amon (who had passed Bell). It was Ickx who gave the race its principal interest as he ripped through the back markers to make up for lost time, relegating Bell on lap 95.

When Rodriguez had led the race from laps 82 until lap 100 (with only eight more remaining) it seemed for the second time this year that luck might just be on the side of Bourne, but it was not to be. The Mexican started his 101st lap in the pit lane, rolling in for fuel with a dead engine. It seemed incredible after St. Jovite that BRM should let such a thing happen again, but happened it had and there was the red, white and gold Lotus 72 of an incredulous Fittipardi going by into the lead of the richest race of the year. Rapid pitwork got Rodriguez back into the race just in time to prevent Gold Leaf Team Lotus making a completely clean sweep of it and Fittipaldi reeled off the remaining eight laps to take his first Grand Prix victory. Wisell was indeed happy with third place, but Ickx took Amon’s fourth place away from him with two laps left. It was not enough to keep Ickx in the hunt for the World Championship, which now goes to the late Jochen Rindt. Few would disagree that it was appropriate that a member of Team Lotus should have prevented Ickx from keeping in the Championship running.

Fittipaldi receives the trophy on the podium

Motorsport Images

When Motor Sport initiated its Formula Three Championship earlier this year, pictures of the four most prominent Formula Three drivers were published as an introduction to the Formula for readers. These four were Peterson, Schenken, Fittipaldi and Wisell: all four have now become established members of the Formula One scene, Wisell being the last to join. While we mourn those we have lost, we must welcome these newcomers and their obvious talents.

M. G. D.

Results:

12th Grand Prix of the United States – Formula One – 108 laps – 400 kilometres – Dry

1st:E. Fittipaldi (Lotus 72C/R5) …………………. 1 hr. 57 min. 32.79 sec. – 204.05 k.p.h.

2nd:P. Rodriguez (BRM 153/05) ………………… 1 hr. 58 min. 09.18 sec.

3rd:R. Wisell (Lotus 72C/R3) …………………….. 1 hr. 58 min. 17.96 sec.

4th:J. Ickx (Ferrari 312B/001) ……………………. 1 lap behind

5th:C. Amon (March 701/1) ………………………. 1 lap behind

6th:D. Bell (Surtees TS7/002) ……………………. 1 lap behind

7th:D. Hulme (McLaren M14A/2) ………………… 2 laps behind

8th:H. Pescarolo (Matra-Simca MS120/02) …… 3 laps behind

9th:J. Siffert (March 701/5) ………………………. 3 laps behind

10th:J. Brabham (Brabham BT33/2) …………… 3 laps behind

11th:R. Peterson (March 701/8) ………………… 4 laps behind

12th:R. Stommelen (Brabham BT33/3) ……….. 4 laps behind

13th:G. Regazzoni (Ferrari 312B/004) …………. 7 laps behind

14th:P. Gethin (McLaren M14A/1) ……………… 8 laps behind

Fastest lap:J. Ickx (Ferrari 312B/001), on lap 105, in 1 min. 02.74 sec. – 212.39 k.p.h. (new Formula One record).

Retirements:J. Surtees (Surtees TS7/001), loose flywheel on lap 7.

G. Eaton (BRM153/03), engine, on lap 11.

J. Oliver (BRM 153/06), engine, on lap 15.

G. Hutchison (Brabham BT26/3), loose fuel tank, on lap 22.

J-P. Beltoise (Matra-Simca MS120/03), handling, on lap 28.

J. Bonnier (McLaren M7C/1), assorted troubles, on lap 51

T. Schenken (De Tomaso 505/38/3), broken sub-frame, on lap 62.

F. Cevert (March 701/7), lost rear wheel, on lap 63.

G. Hill (Lotus 72/R4), clutch, on lap 73.

J. Stewart (Tyrrell 001), oil leak, on lap 83.

24 starters – 14 finishers.