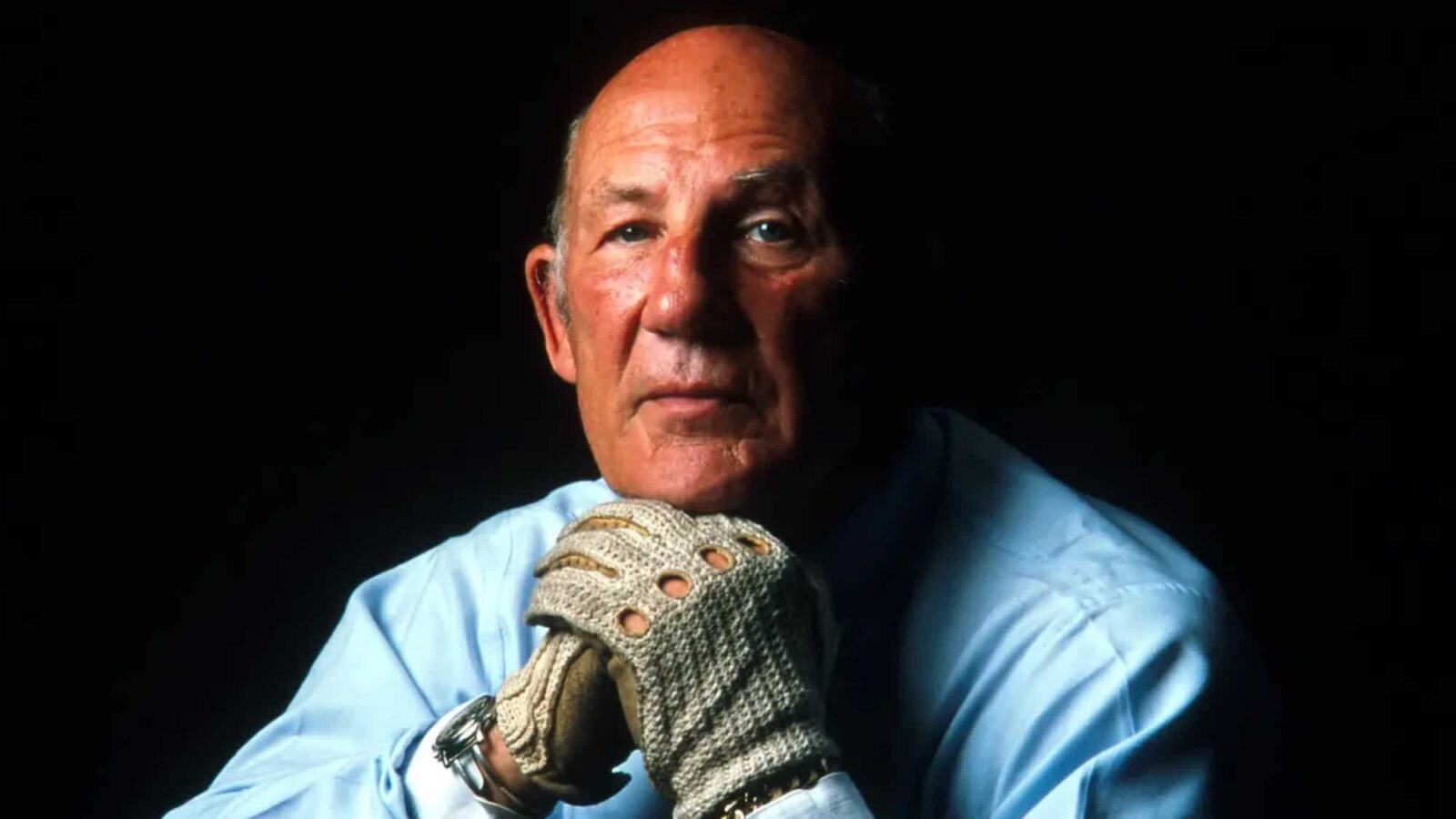

Stirling Moss

It seems incredible that Stirling Moss is 70 years old, it is nothing to the fact that, despite a career lasting for just 15 of them, he's still our greatest sporting institution. Robert Edwards examines the Moss phenomenon and finds much more to the man than simply a fabulous talent.

Charles Best

“One day”, opined a chum in a very world-weary way, “there will be a racing magazine issue which doesn’t mention Stirling Moss.” I.T.M.A. syndrome. It’s That Man Again.

Well, tough, because this issue is not one of them. Stirling Moss is 70 on September 17, and, to the frustration of some in Formula One, he remains one of British motorsport’s most important and durable figures. And of his era, he is most important of all and not entirely because he has spent more of his life just being Stirling Moss than actually doing what it was that made him famous in the first place.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about him is that he has fans who never saw him race. At the Australian Grand Prix two years ago the biggest banner in the crowd simply announced ‘Stirling Moss’. A World Championship Australian Grand Prix was nearly a quarter of a century away when Stirling last raced. Just consider that.

Not many people receive sacks of unsolicited gifts on their birthdays, or whose address the Royal Mail does not need to know. “Stirling Moss, England” has been known to reach him. Presents, many simple and hand-made, regularly turn up, sent in tribute to a man who has simply, and not entirely as a result of his own efforts since his early retirement, become an icon.

When Churchill was asked how it felt to be eighty-five, he replied: “considering the alternative, wonderful.” It is the kind of crass question which demands an ironic answer, but the reason for its being posed was that Churchill was one of the most important men of his generation, and in a sporting context, so is Stirling Moss.

Why is he important? Well, he occupies centre-stage in our interests because of a bemusing variety of characteristics. He was a professional, always, but believed he needed an edge to succeed, despite the opinions of those around him that he did not require special brakes, the latest cylinder head, this chassis, those shock absorbers. Those who know say this was merely a manifestation of a lack of self-confidence on his part and that, with cruel irony, he matured years in a tiny space of time after he crashed. In a sense, Moss was right; progress is all, but so were they. The truth can be examined only in retrospect.

Because we adore this sport, we know the view of those who know is probably true, and while the realisation makes us blush for our own lower-fburth enthusiasm fbr anything with five wheels and an engine, it does not stop us marvelling at a man who did more by example to make this country aware of its own shortcomings than anyone else in sport, except arguably Denis Compton.

For this is what sports stars do, and Stirling, like Compton, was undeniably a star. He exuded an air of being in control, even if he wasn’t. Like Compton, he appeared to have all the time in the world to do his job and his audience, beset by the difficulties of economic crisis, rationing and postwar gloom, applauded him. He was the boy wonder, beloved of fiction and rare at any level.

Despite his competitive nature, he was capable of great acts of sportsmanship; his support of Mike Hawthorn at the stewards’ enquiry in Portugal in 1958 is the best-known example, (although there are others) because it probably cost him the World Championship. His unsolicited sense of charity in buying and equipping an adapted van for a polio victim represented an even more radical attempt to level the playing field.

This is not the place to go through those great Moss races, we are all aware of them, or indeed the dreadful mishaps which befell him, as they are now part of the sport’s folk memory, particularly those at Goodwood and Spa, but it is appropriate to look at those aspects of him which to set him apart, put him in that special category reserved for icons.

Stirling was ahead of his time in several ways; racing was his core business and whereas several contemporaries used it to promote other activities, be they the car trade or otherwise, he did not. He sought product endorsements, for example, and the combined efforts of his father Alfred and his manager Ken Gregory put him within the commercial ken of several companies, particularly BP which were to be vital to their plans and, as it turned out, to his own.

That this approach to the business of racing caused eyebrows to be raised is a matter of record, but then so is Stirling’s resume. He is, by volume, Britain’s most successful racing driver, and thus by derivation probably her most successful sportsman.

All the usual measures apply. More people saw Stirling at work than any other Brit; the 1955 Mile Miglia, for example might well qualify as the best-attended sporting event which had taken place on the face of the planet, and he won it, in a record time which was never beaten. More’s the pity so few got the chance. Something like nine million people actually watched at least part of it; without the aid of television. They turned out to see it. That it was free was not the point. This was, after all, Italy.

But it was his professionalism which set him apart not merely his mastery of a motor car, but his intuitive (and very modem) grasp of the power of sponsorship and public relations. In that sense, given his occupation now, he could even be said to be a PR man who raced for a while. This was well illustrated by deciding to drive for Maserati in ’56 on the advice of a panel of journalists. That they were flattered reflects not so much a manipulative cleverness on his part (although it was a very clever thing to do) but more a total lack of confidence on their part (and his) concerning the suitability of any British machinery available for him to drive. Difficult to criticise a decision in which they had been so instrumental…

His relationship with his manager Ken Gregory was unique for the times as well; nowadays all drivers, even those of modest talent, have commercial managers, or those who at least so call themselves, but in the ’50s it was a rarity. Denis Compton had one too, of course, and also endorsed products. It would have been pointless for Stirling to endorse Brylcreem, of course, but Lucozade was another matter.

Moss was also probably the first sports personality to be commercially important in the sense his sponsors started to consider him as economically significant, never more so than at the time of the de-merger of the Shell-Mex BP marketing operation. Moss literally became the face of BP; became identified with them (and they with him) to an unprecedented degree. In that sense, his simple commercial importance, way ahead of its time, has seldom been matched, or even approached. He almost became a brand in himself.

Another modem note was the fact he was more or less teetotal; none of this “my body is a temple” nonsense, but for the more mundane reason of the nephritis which had also, to his frustration, barred him from National Service. In an age when drivers were strong rather than fit (and sometimes quite squiffy) his abstinence was a major asset.

It was a hallmark of Stirling’s reputation that his mere presence on a grid could boost sales; he was popular with fans because he waved at them and organisers liked that rather a lot. He and his team had a simple doctrine; value for money. He repaid his financial supporters with the full coin of his mind and with an urgency which reflected the brutal truth that all this could end almost at any time with a single lapse of concentration. And end, of course, it did. ,/p>

So Stirling became a very modern racing driver indeed and has been so recognised by his more modern counterparts; an unavoidable spectacle in the entrance of Stirling’s extraordinary house is a picture presented to him by the late Ayrton Senna. “With respect.”

Of all the words written about Moss, the following passage of purple prose perhaps encapsulates the esteem in which he was held in his prime, even by those who didn’t go motor racing, for he mattered to them as well:

“It’s because he was a knight in armour, rushing out to do battle in foreign lands, and coming back, sometimes with the prize and sometimes without it; sometimes blood on his shield and sometimes not but always in a hurry to have another go at the heathen.”

Stirling actually had a suit of armour at the age of seven; his father Alfred made it for him, from tinplate and solder, and not for reasons of economy, either. Alfred, like his son, was a man of his hands; he was an inventor, an improver, and reckoned that he could often do a better job than the professionals, In this he was probably right, and it is a trait Stirling inherited, expressed by buying expensive luggage and rebuilding it so it works better; or, more famously, designing his own house.

He went so far as to seek advantage on the track by attempting modifications to his cars which were not always necessary, (and not always wise), and in this he rather differed from his father. When Alfred Moss raced in America in the 1920s (twice at Indianapolis, a thing his son never did), the car to have was a Frontenac-Ford, the Reynard of its day, designed by Louis Chevrolet Few attempted to improve them. In obtaining one (they were highly sought after) Alfred was not above the odd small deception, contriving to ‘lose’ a letter of introduction in Chevrolet’s outer office and persuading the unsuspecting secretary to retype it with suitable embellishments.

But Alfred was a rigorously honest man in every other respect; a plain dealer and a generous friend. He passed on many of these attributes to his children, but it was clear early on that an appreciation of motor cars was not necessarily one of them.

For petrolheads, it’s hard to comprehend that a driver of Moss’s calibre might not actually appreciate cars, but surely it is also clear that given how a racer is supposed to drive his vehicle, then he looks to it for totally different things from the mere car fan. No-one who has heard the tortured shriek of metal within a few revs of becoming scrap need be in any doubt that the cruel and unusual treatment which a racer hands out to a car rather implies that to care about cars, to be sentimental about them, is folly. Perhaps to a racer, a road car is merely an item of white goods. Stirling regularly drove a Lotus Elite road car, and praised it, even though it was clear that the frightful accident which befell him at Spa in 1960 was caused by a wheel dropping off the Lotus 18 he was driving. Not the car’s fault, merely the manufacturer’s.

Artists, I have noticed, are unemotional about their works, even though intimately connected with them. The economic function they play in the artist’s life, governing all aspects of it, is perhaps even a cause to resent their output, and any appreciation which they may feel is confined not to their past but to their future efforts. For them, the work is for selling. That is its economic function.

Stirling Moss, who was undoubtedly an artist, has said he has never driven a perfect lap. Many who saw him work disagree, and some would even say it was not his place to pass an opinion – he should let others be the best judge of that They are wrong, of course, because the pleasure we obtain from watching a Moss, Senna, Ali or Nureyev at work is knowing that at that moment they are giving of their best, and that the inconsistency from which the rest of us suffer is apparently unknown to them. That is our perception and we should really try to hold onto it, not solely for our sakes, but for theirs, too.

The beguiling honesty of a man says “I might well have finished the Mille Miglia without Denis Jenkinson, but I couldn’t have won it” is rather at odds with the “My game was great today – my ground-shots (or left jab, tee-shot or blatant rule infringement) were very strong and it felt good.” Quite apart from the linguistic abuse such statements encourage, there is the whiff of bullshit about them. The post-Grand Prix press conference is a classic of this atonal genre. “The package was very strong.” Gaghh!

If you listen to a truly classy racing driver, it is clear there is confusion in his mind as to what all the fuss is about, particularly now, when the risk of injury is so modest and the machinery so varied in ability. Many interpret this as being merely a gripe about money, and that is a large part of the bewilderment, but more than this, there is a genuine sense of wonder that so many seem get so much out of what seems so very little. Stirling has summed it up for me as “a great occasion, but not a sport.”

For the man who did more than many to turn F1 into what it is today, this is an attitude which seems superficially disingenuous and unworthy of him, but when pressed he will repeat it and we can only assume that he means it. For the man who bears so many scars on his body and in his memories, it is an attitude which is most breathtaking, for Stirling’s love of the thing which nearly killed him still beams through. It goes a long way toward accounting for why he is a national treasure and will, I maintain, remain so.

So, happy birthday Stirling. Considering the alternative, it really is very good to have you still with us.