Page 13

Matters of moment, October 1964

The show Another S.M.M.T. London Motor Exhibition opens at Earls Court on October 21st. Allis is an-annual happening which signals…

The show Another S.M.M.T. London Motor Exhibition opens at Earls Court on October 21st. Allis is an-annual happening which signals…

The Constructors' and Drivers' World Championships will be competed for over eleven events in 1965 (see page 805). The first…

In our September issue we gave the positions in the Championship as far as Craigantlet, where Peter Westbury had once…

Following up last year's “demonstration" at Brighton, when Americans Mickey Thompson and Dante Duce came over to show the potentialities…

Nineteen sixty-three was a vintage year for new cars as the Motor Show saw the British debut of such cars…

With regard to the unquestionable victory by Surtees for Ferrari, with the V8-engined car, I can only refer to my…

The trend of fitting large capacity American push-rod V8 engines in European style chassis, both single-seater and sports-racing has come…

I must start this month's notes with a postscript to my remarks in the last issue of Motor Sport concerning…

Just as we close for Press the results of the Tour de France were announced. In the Touring category the…

Former Mercedes-Benz Formula One racing driver, Hans Hermann of Stuttgart, will be rejoining the Mercedes team for the eighth Argentine…

A useful aerosol-applied spray paint is now on the market, which, apart from the obvious household applications, is handy for…

The British Drag Racing Association started their festival of accelerative speed at Blackbushe aerodrome in Surrey, on September 19th, and…

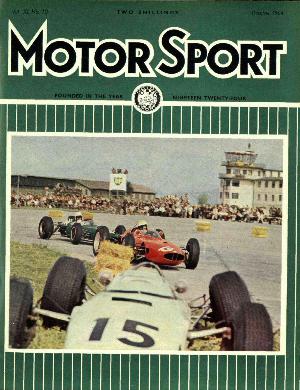

A close race September 19th Despite an almost complete lack of pre-race publicity, a good crowd turned up at Oulton…

This year there were no arguments or discussions about how the Italian Grand Prix was to be run, for right…

Eagle-eyed students of results will have noticed that Surtees had his rear suspension collapse while he was on lap eight,…

Usually this feature is made up of extracts from old books, in which references to cars, preferably biographical but sometimes…

"Alfa Romeo—A History," by Peter Hull and Roy Slater. 513 pp. 8½ in. x 5¾ in. (Cassell & Co. Ltd.,…

Whatever your opinion of dragsters, the 1st British International Drag Festival, sponsored by The People, has provided something entirely new…

The outstanding recent car miniature is a fine 1910 38-h.p. Daimler tourer in the new "Corgi Classic" series. It is…

In perfect September weather the Goodwood season came to a close on September 12th. As we journeyed to the last…

There is surely nothing better than having eight fast motorcycles and eight fast riders on the MotoGP grid. But it’s not always that simple, as Ducati management found out at Sepang

Jorge Lorenzo will race at this season’s MotoGP Catalunya Grand Prix, seven months after announcing his retirement from motorcycle racing. The three-time MotoGP champion will take Yamaha’s wildcard entry for…

The Jakarta ePrix has been postponed due to coronavirus, becoming the third Formula E event affected by the outbreak. The race was due to be held on June 6, but…

Competition: enter now to win