Page 23

Matters of moment, November 1973

Showtime Soliloquy Motor Show time in Frankfurt, Paris and London is an appropriate period for thinking about the state of…

Showtime Soliloquy Motor Show time in Frankfurt, Paris and London is an appropriate period for thinking about the state of…

Matters of Moment 1265 Fixtures for November 1266 United States Grand Prix 1267 Continental Notes 1270 New Safari Rally Route…

Surface Mail: Home £2.80

Only clubs whose secretaries furnished the necessary information prior to the 14th of the preceding month are included in this…

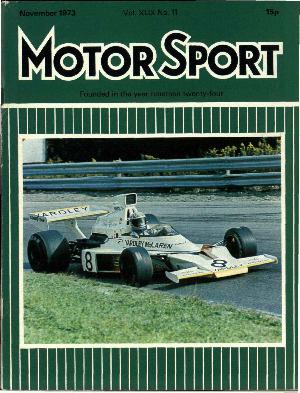

Watkins Glen, U.S.A., October 7th The most arduous year of racing in the history of the World Championship came to…

Ferrari Dino 308 GT4 Anyone who has driven, or even ridden in, a Dino Ferrari 246 G will know that…

At a time when some rallies are changing their dates in order to move away from the disturbing Influence of…

Once again little inspiration was to be gained from the Earls Court Motor Show, overshadowed as it was by the…

What was a great season for the Elf Team Tyrrell organisation came to an unhappy end at Watkins Glen when…

After a professional international career of ten years, three times World Champion John Young Stewart announced his retirement from active racing…

The Editor talks with Walter Hassan, OBE, AMIMechE, until his recent retirement Chief Engineer of Jaguar Cars Ltd., about his…

For the moment the flood of hooks about cars has slowed down but no doubt the tide will flow again…

Grand Prix Models of 173-175, Wading Street, Radlett, Herts, can supply a big plastic kit which makes up into a…

The Honda Civic I find these days that I like little cars very little. The Honda CiVic is an exception…

By the Hon. Alan Clarke 2,000 Continental Miles in a Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost A Rolls-Royce 'Rally' is to me something…

A Section Devoted to Old-Car Matters VSCC Welsh Week-End (Oct. 6th/7th) That excellent institution, the VSCC Welsh Rally and Trial,…

A news-release from Stan Nowak of New York informs us that there was an important break-through in vintage car racing…

Long-distance charity walks, in which the too-young, the old, and fit in-betweeens frequently take part, at best becoming halt and…

Vintage Le Mans Sir, Oh dear, did three nasty gentlemen beat D.S. J.'s old travelling companion Stirling Moss at the…

Sir, Some years ago a "racing" Essex was mentioned in your columns and I enclose a photograph of this car…

A chaotic, crash-strewn IndyCar race in the streets of Sao Paulo on Sunday got its act together in the closing stages to produce a superb three-way battle for the lead…

Circuit Dijon-Prenois only held seven GPs and was criticised by some, but still managed to produce some famous moments in F1 history

A few weeks ago, if you had suggested to Sebastian Vettel he could potentially sign a new deal with Ferrari before the first race of the season, he would likely…

The Aston Martin name will return to F1 next year... and the Mercedes team principal has invested in the company. What does Toto Wolff's stake mean? Mark Hughes has the answer.