Obituary

T. C. (Cuth) Harrison It was with some degree of shock that I heard of the death, at 74, of T. C. (Cuth) Harrison for only last summer I had…

Lyndon McNeil

Belfast wasn’t an obvious hub of motor sport during the 1950s and 1960s, but you could savour your fair share if you had the right attitude. Fred Gallagher had the benefit of a car-mad father – “I’m a Frederick, he was ‘Fred’” – who attended a catalogue of events that had a big influence on his son’s future ambitions. It probably didn’t help that rally talisman Paddy Hopkirk lived just across the road, either.

“I have vague recollections of going to Dundrod when I was small,” Gallagher says, “but my earliest memories would be going to watch races at Kirkistown and Bishopscourt, plus the Circuit of Ireland rally… I looked forward to Easter more than Christmas because it was Circuit of Ireland time. We also attended hillclimbs, autocrosses and autotests – and Dad was quite intrepid. He thought nothing about taking the ferry to Stranraer and then driving to Brands Hatch or wherever, long before there were any motorways. In 1964 he took the family to the Reims 12 Hours in my gran’s Mini – and in 1969 we travelled in his Ford Anglia to the French Grand Prix, at Clermont-Ferrand. There were only 13 starters, but it was still a stunning experience.

“I have very fond memories of the 1962 Motor Six Hours at Brands Hatch. Paddy Hopkirk was sharing a works Mini Cooper S with John Whitmore and we were standing to the outside of Stirlings. I was about 10, waved at Paddy every time he came past – and he’d always wave back. After he handed the car over, John Whitmore gesticulated crazily at us on his first lap, so Paddy obviously briefed him.”

But, why did fate steer Gallagher towards stage rather than track? To hear his tale, we convene at The Anchor Inn in Lower Froyle, Hamphire, where Fred warms up with a glass of Sauvignon Blanc, before switching to Shiraz to accompany haunch of venison with mushroom dauphinoise.

“Even back then,” he says, “the cost of going racing would have been fairly horrendous – rallying was more accessible, plus I had been obsessive about maps for a number of years. My uncle did an event with leading co-driver Terry Harryman, who made the mistake of leaving his Northern Ireland maps on the car’s back seat. I borrowed them and copied his markings before giving them back. I’d return from the Circuit of Ireland and sit in my bedroom, looking at a road map and pretending I was doing a rally. I was a theoretical navigator long before I was an actual navigator.”

Gallagher has sat alongside some of the greats, such as Henri Toivonen, here in the works Opel Ascona in 1982

He got his first taste of competition with a local printer, Raymond McKnight. “I can’t recall how we met,” he says, “but in those days printers earned a fortune and he had a Cortina GT. We did road rallies and even a stage event in which we were seeded last and certainly didn’t pass anybody.”

Studies threatened to disrupt his competitive ambitions when he went to Dundee University to pursue a dentistry degree, but there he befriended a like-minded Canadian and the pair would set off in a Mini most Friday evenings “to watch anything decent that was on during term time”… even if it was 480 miles away at Brands Hatch.

“Rallying started properly after I failed my first-year dentistry exams,” Gallagher says. “I went back to Belfast and worked in a civil engineering office, where I fell in with some people who went rallying every Friday night. I’d go along to navigate with a variety of different drivers. One of the first was Jimmy Ogg, who had a 1098 Mini. I suffered from car sickness on the first events I did. I remember thinking, ‘If I wasn’t ill this wouldn’t be that difficult.’ That clearly isn’t true, but once I overcame the sickness, we were usually in the top six – against some very good people.

“The quickest of the Mini drivers was a guy called Irvine Tannahill, who asked whether I’d like to join him in his Cooper S. He and I hit it off; I was getting better, he was quick, the car was quick and we actually won a Northern Irish Rally Championship event outright against the establishment in their Porsche Carreras and stuff. That was by far the biggest thing that had ever happened to me.”

During this period Gallagher was also taken under the wing of Malcolm Neill, a man he describes as “Northern Irish motor sport royalty. His father had been clerk of the course at the Dundrod TT, very high up in the Ulster Automobile Club and a fairly strong character, a lot of which rubbed off on Malcolm. The Circuit of Ireland was cancelled in 1972, at the height of ‘The Troubles’, and Malcolm decided come what may that the event was going to run the following year. At the time he was a chain-smoker who drank copious amounts of gin and had a 3.0 Ford Capri he drove flat-out everywhere. This was during my ‘gap’ year, before I went back to university, at Aston, to train as an optician. Every Friday night, he would pick me up and we’d go off to Killarney or wherever, recce for the following year’s Circuit and prepare a roadbook. I learned an enormous amount.”

Gallagher did the Circuit for the first time in 1974, alongside Tannahill, and the following year received a letter from Neill. “He said there was a Swedish privateer coming to do the Circuit, Bengt Lundström, and he wanted a local co-driver, so would I do it? Of course I would! Bengt was a fairly wild Swede, and we crashed within five stages, clearing a hedge and landing upside down in a field. As I crawled out through the front screen, I looked up and my dad was standing there…

“They had a thing called the Sunday Run then, so if you’d retired you could continue at the back and do the classic Kerry stages, which we did. Then Bengt bumped into works Škoda driver John Haugland. Norwegian and Swedish being pretty similar, they started chatting. Although I couldn’t understand, I could feel they were talking about me. John then said to me, ‘I understand you’re a student. D’you get long holidays like they do in Norway? If so, would you like to do some rallies with me..?’

“Come July, I caught the boat to Liverpool, took the train to Harwich, then a ferry from Harwich to Oslo: I had £25 with me, all you were allowed to take out of the country back then – and possibly all I had anyway! John drove the rally car and I drove the recce car, from Oslo to what was then Gottwaldov but is now Zlín. We carried on day and night – the only time we slept was on the ferry from Sweden to Germany. We went through Dresden, where there were still Bailey Bridges on the motorways, even in 1975, because the originals had been bombed. And I’ll never forget sitting at the Czech frontier, which was pretty grey. We recced hard for the Barum Rally and came second – with me reading the notes in Norwegian. That wasn’t the difficult bit, because there were only about 10 words. The toughest thing was the pressure I felt.

“John then asked whether I’d like to do the RAC – so my first world championship event was in a works car and we finished 15th overall and first in class. We got on famously, did Sweden the following year – and all while I was still at university.”

This time he completed his degree and settled down to work for an optician in Ferndown, Dorset – which is where he was when the phone rang shortly before the 1976 RAC. It was John Davenport, British Leyland’s competition manager, whom he had first met while co-driving for Haugland.

Could have been a dentist, was an optician, but Gallagher made his name in rallying

“John asked whether I’d like to partner Tony Pond in a Triumph TR7 in 1977. Talk about cloud nine… He suggested we do the Boucles de Spa, to make sure we got along, and that he’d formalise a contract after that. The next day I got a call from Russell Brookes, who asked if I’d co-drive his works Escort in the British Rally Championship, while he was also going to start the European series and see how that went. Who was I to say ‘no’ to Russell Brookes? He said we should do the Tour of Dean together, in January.

“I couldn’t really turn either of them down, because if I didn’t get on with one it would be my luck that I’d turn down the other. So I went off with Russell on the Tour of Dean and we were lying second when we retired. Then I came home and almost immediately went with Tony to Belgium, where we won – my first international victory, so I was on a real high. When I got back, I picked up that week’s issue of Motoring News… and there was the entry list for the Mintex Rally, in which I was seeded at both three and seven!

“I ended up having an interesting conversation with John, during which I explained that there had been no guarantees so I couldn’t turn anything down. We had a bit of an argument – the only one we ever had. I said, ‘Well, if it’s going to be like this, I’d better go with Russell…’ We both slammed down the phone and at 5.30 I walked out of the office to find John’s Rover SD1 in the car park with the window open. ‘You – get in!’ We drove to the local pub and John said it had all been a great misunderstanding. Russell was working for Land Rover, which at the time was part of British Leyland, and John said he’d had a discussion with Russell and sorted it out, I’d be partnering Tony and here was my contract. So I signed up, which was great except that he hadn’t spoken to Russell, who called me in a fairly upset frame of mind the next day and then didn’t speak to me for about five years – although we eventually got over it.

“With the benefit of hindsight, I didn’t handle the situation very well, though it was 100 per cent the right decision in career terms. I might have won three Circuits and a couple of Scottish Rallies if I’d gone with Russell – I’ve never won an international gravel rally in the UK, while several of my contemporaries have won dozens – but the Tony thing was a first step into the big, wide world. We had a really good 1977 getting to know each other – second on the Mintex, third on Elba – then in 1978 I’d say we got our first big wins, Ypres and the Manx, both of which we dominated.”

Pond was one of the UK’s great unfulfilled hopes, a driver with success in the UK, Europe and South Africa who never quite achieved the anticipated success on the world stage. How did Gallagher rate him?

Björn Waldegård and Gallagher formed a potent partnership at Toyota, which included success on the 1986 Safari Rally

Motorsport Images

“From my perspective,” he says, “Tony was as good as any of the world champions I sat beside, certainly from the driving side. He was a bit of an enigma, though. He had massive self-confidence on one side but on the other he was very insecure. The biggest example would be late 1980, when we knew Triumph was pulling out at the season’s end. There was a national event in Wales, two weeks ahead of the RAC, and Toyota was also doing it. At the service area I got chatting to [Toyota team manager] Henry Liddon, who asked whether Tony and I would like to sign up alongside Björn Waldegård, which I thought sounded pretty special. Tony flew over to Cologne and was offered a full WRC contract, but he turned it down because they wouldn’t build him a right-hand-drive car. I never saw Colin McRae or Richard Burns not wanting to drive because the steering wheel was on the left… Tony would have driven a left-hand-drive car very well – he proved that when he had a run in the Chequered Flag Lancia Stratos – so I think that was a major mistake. We’d have maintained our partnership had he signed and who knows where we might have gone.”

The two also spent 1979 apart, Pond having agreed a deal with Talbot. “I opted not to go with him,” Gallagher says, “because I didn’t have a good feeling about the combination of Tony and [Talbot rally boss] Des O’Dell – and they fell out very early on. John Davenport asked me to stay with Triumph, without a full-time driver, but there was a Chequered Flag TR7 that was mostly driven by Derek Boyd. We did the Galway and had a big accident, which led to me spending two months in hospital. I was still trying to recover when I returned, wanting to know whether I remained brave enough to do it. I went to California to contest La Jornada Trabajosa with John Buffum – we were always likely to win, even if I’d read the notes back to front, and we promptly did. I arrived with a walking stick and went home a week later without it… although it’s difficult to get rid of a walking stick in Los Angeles Airport. Every time I left it somewhere, someone would come running up, ‘Buddy, you left your cane…’” [Gallagher would later partner Buffum on a number of events, the pair winning the 1984 Cyprus Rally in an Audi quattro – to this date the only European championship win ever recorded by an American driver.]

Pond returned to BL in 1980, but his subsequent decision to spurn Toyota left Gallagher potentially on the sidelines – until a chance conversation on the steps of RAC Rally HQ. “Henri Toivonen was walking out as I was walking in,” he says. “We stopped, shook hands, chatted and I asked who’d be co-driving for him in ’81. He wasn’t sure, so I wondered whether he’d consider me and he replied, ‘Absolutely, would you like to do it?’

“We didn’t sit in a car together until the recce for the 1981 Monte… when Michèle Mouton came up alongside in her Audi quattro, challenged us to a drag race and vanished down the road. I guess we’d just seen the future.

“Henri was four years younger than me, but we got on extraordinarily well – that’s been one of the luckiest things in my career, I’ve never been paired with a driver who made me feel I didn’t want to get in the car. We got good results early – fifth in Monte, second in Portugal, second in Sanremo, where we won the unofficial ‘Coupe des Hommes’ behind Michèle and Fabrizia Pons…

“Talbot then pulled out and we went together to Rothmans Opel to do the British Rally Championship. I think it’s fair to say we didn’t feel loved there, the one team in which I’ve never perhaps been fully integrated. We got some decent results – third on the Acropolis and RAC in 1982, victory on the ’83 Manx – and at the end of that season Henri was wanted by everybody. He had offers from Peugeot to drive the 205 T16, from David Richards to do what we thought at the time would be a WRC programme in a Porsche 959, from Cesare Fiorio at Lancia…

“During the Sanremo recce, Henri and I went to Fiorio’s yacht and sat off the coast of Portofino watching the GP of Europe on TV from Brands Hatch. After that we shook hands on a deal to join the team the following year. Henri ended up with contracts to do the WRC with Lancia and the European championship with Rothmans Porsche. David Richards felt that would be too much for one co-driver, that I should do the WRC with Henri and somebody else should do the ERC. Henri agreed, but I didn’t and said, ‘I’m either your co-driver or I’m not.’ We ended up going our separate ways – and given subsequent events [Toivonen and co-driver Sergio Cresto perished in a fiery accident on the 1986 Tour de Corse] that might have saved my life. Who knows?

“My big memory from then is the 1983 1000 Lakes, in an Opel Manta. We were supposed to be outclassed by the quattros and the Lancia 037s, but there were a few stages in the dark – and Henri was either quickest or second fastest on all of them. Years later, after Jari-Matti Latvala set his first quickest WRC stage time on the Monte, he was in a queue with me at Nice Airport. I congratulated him and he replied, ‘Never mind that – tell me about doing the 1000 Lakes with Henri.”

With that partnership dissolved, it was back to chance conversations.

“This might sound familiar,” he says, “but in our hotel bar at the 1983 RAC Henry Liddon mentioned this youngster Toyota would be running – Juha Kankkunen. He asked me to call when Christmas was over, but probably wasn’t expecting me to phone at 9.01 on Boxing Day… Henry ran an incredibly good outfit, we had a great couple of years – and I won the Safari at my first attempt, in 1985. The previous year they hadn’t allowed Juha and I to do the event because we didn’t have any experience.

“We were seeded at 21 and Motor Sport’s rally reporter Gerry Phillips went to check the odds at a local bookmaker, saw that Kankkunen/Gallagher were 500/1 and put about £100 on us… On the flight out Juha and I were sat in economy and knew Henry was up in business, so we wandered to see him. He was stretched out with his gin and tonic so we gave him a bit of friendly stick. He said, ‘Tell you what, if you two newcomers get to the finish you will fly back in business’ and as we were walking away, he added, ‘And of course if you win, you’ll fly back in first…’

“We knew that Shekhar Mehta nearly always finished in the top three. With all due respect to Shekhar, Juha was a quicker driver and the Celica Turbo was a better car than his Nissan 240RS. We decided that if we went at Shekhar’s pace, then put in a sprint near the end, we’d probably beat him. We were 10th when we arrived in Mombasa, seventh when we got to Nairobi the first time, fifth at Mount Kenya and then third behind the Opels of Rauno Aaltonen and Erwin Weber when we got back to Nairobi. The final section started at eight in the evening and finished the following midday. We were asked to up our pace a bit – and nearly went off twice, so we both agreed we’d be happy with third.”

That became first when both Opels hit trouble – and despite a broken rear damper adding a frisson of unwanted tension, they held on. “When we got back to the airport, Henry and the man from Swissair were there with two first-class boarding passes.”

Gallagher had the chance to go with Kankkunen to Peugeot in ’86, but felt comfortable with Toyota and decided to stay put. “Ford offered me a place alongside Stig Blomqvist in a works RS200 for exactly double the salary Toyota was proposing,” he says. “I telexed Toyota, telling them I couldn’t afford to turn down such a chance – and Henry replied to let me know he’d match it.”

Gallagher entered what would be the final phase of his mainstream WRC career alongside 1979 world champion Björn Waldegård, the duo winning the Safari and the Ivory Coast in 1986 – and the Safari again in 1990, by which time their commitments to Toyota were scaled down. “Things quietened after 1988,” he says. “Toyota kept Björn for the Safari and a few other bits, but in 1991 we were told we’d also be doing the RAC – and when the entry list came out, we weren’t on it. I got a bit nervous about that, but they kept insisting we’d have a car for the 1992 Safari. In the end Björn was offered a Lancia deal instead, which ended unfortunately. We came out of this long gravel section onto asphalt and into a time control. We had about 50sec for a free service and didn’t need to refuel, but we thought we might as well do it. We sat there with the engine ticking over and one of the mechanics let a drop of fuel spill onto a hot brake disc, which ignited and caused him to drop the whole jerrycan. Whoosh…”

He doesn’t name the individual, but adds, “I’m fairly sure I know who it was and he’s now an F1 team principal…”

Gallagher was also by then carving a fresh niche in the FIA Cross-Country Rally World Cup.

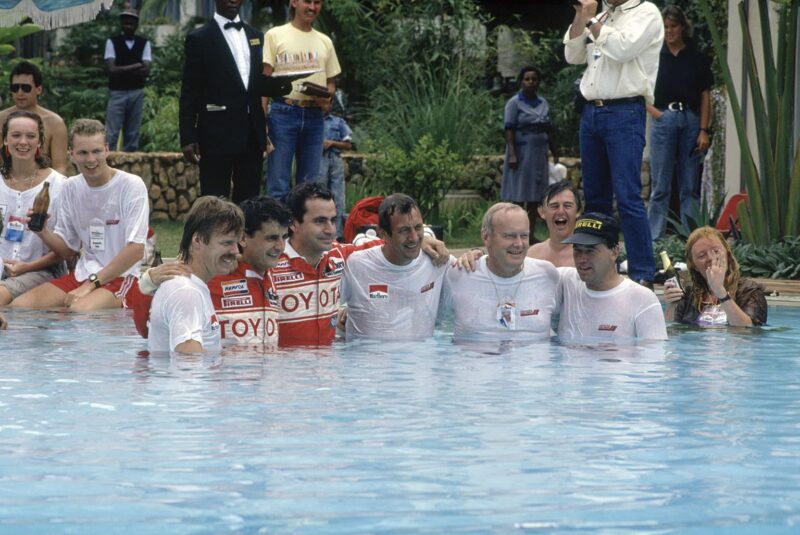

The Toyota team cools off to celebrate 1990 Safari victory, from left Mikael Ericsson, Luis Moya, Carlos Sainz, Claes Billstam, Björn Waldegård and Fred Gallagher

Motorsport Images

“In 1990, Björn had been asked to do the Dakar in a Peugeot,” he says. “He came back and said he needed a WRC-type co-driver, so could I do it? We signed with Citroën at the end of 1990 – and I was there until the programme ended in 1997. I didn’t do every event, but most of them. People assume there’s a similarity between the Safari and Dakar, but Björn and I felt totally at home on the former – and after my first win I was always confident I’d be able to challenge for victory. I never went into a desert event with anything other than a bit of trepidation.”

After Waldegård retired at the end of 1992, Gallagher spent a few seasons alongside double WRC champion Timo Salonen – “An incredibly calm character, who always smoked – even on the stages. He’d give me two packets, and I had to hand them over as required. He threw the butts out of the window and they always ended up in the air intake mesh, so the mechanics could tell how many he’d smoked.”

They won their first event together, the 1993 Pharaohs Rally, plus the 1994 Baja Aragon, but never finished better than fifth on the Dakar, in 1995. The following year Gallagher partnered Philippe Wambergue on the event – and finished second. “I don’t have many regrets,” he says, “but it would have been nice to have a Dakar victory. In the dunes that year, the steering wheel snapped around and dislocated Philippe’s thumb, which cost a lot of time. He had it relocated while sitting in the car – I had to unplug my headset at that point.”

Citroën offered a limited programme of events for its cross-country swansong in 1997, but… “Due to some misunderstanding with his co-driver,” Gallagher says, “Ari Vatanen had a massive accident in Italy, at the first round. He phoned me on the Monday and told me I needed to be his co-driver. Ari had a reputation for being a bit difficult – and also for crashing quite a bit – and I was now almost 45, so thought, ‘I don’t really need this.’ He called me every day for a week – and on the Friday Citroën rally boss Guy Fréquelin phoned and gave me this great spiel – I was almost in tears by the end of it – and said if I was worried about Ari’s driving, just to let him know and I could stop. But Ari and I got along famously – we won the title and never even had anything approaching a moment. We ended up chatting about what we could have done if we’d forged a partnership years earlier.”

They would team up again with Ford for the 1998 Safari, after Vatanen was recruited to replace the injured Bruno Thiry. “I hadn’t done a WRC event since the 1992 Safari, so felt a bit rusty,” he says. “We were second by the end, though [Ford rally chief] Malcolm Wilson asked us to clock in 26min early at the final control to let Kankkunen through, but we were still on the podium.”

That led to a full season with Ford in 1999, his final WRC campaign. Some years later, the AKK – Finnish motor sport’s governing body – made him a rare non-Finn (“I believe there are three of us”) to have received one of its gold medals for services to the nation.

Gallagher is still active as an administrator and organiser – including a long stint as clerk of the course on Britain’s WRC round.

Gallagher and several colleagues have now set up Rally the Globe, which runs endurance rallies for vintage and classic cars. It hosts its maiden event – the Carrera Iberia – later this year. And he also continues to participate, as both navigator and driver on historic and vintage events – alongside McLaren design & development director Neil Oatley, among others, or at the wheel of a 1939 Lancia Aprilia.

Does competition still give him a buzz?

“It does,” he says, “but then I don’t know much else, because motor sport has filled every aspect of my life to such a great degree.”

He has covered quite some ground these past 45 years; those early family road trips served him well.

Born: 16/4/52, Belfast, Northern Ireland

1975 First WRC start with John Haugland (Škoda) on RAC Rally; class win

1977-80 Factory Triumph co-driver, with Tony Pond

1981 Joins Talbot with Henri Toivonen

1982-83 With Toivonen at Opel; wins Manx International

1984 Moves to Toyota with Juha Kankkunen

1985 First WRC wins – Safari and Ivory Coast

1986 Stays at Toyota to co-drive Björn Waldegård; wins Safari and Ivory Coast

1990 Third Safari victory – the second with Waldegård l 1991 Joins Citroën for FIA Cross-Country World Cup

1993-1995 Partners Timo Salonen at Citroën

1996 2nd on Dakar Rally (Philippe Wambergue)

1997 FIA Cross-Country champion, with Ari Vatanen

1999 Final WRC campaign

2008 Receives AKK Gold Medal for services to Finnish motor sport