Ferrari 312P book review: flawed favourite

The 312P turned heads but unreliability made it a curiosity, says Gordon Cruickshank

The 312P was fragile, but it was put through its paces in the 1969 Nürburgring 1000Kms

Motorsport Images

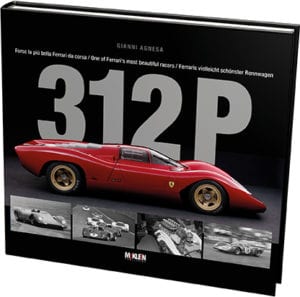

The first thing you need to know is that this book is about the Ferrari 312P, not the Ferrari 312P. They have different engines. It’s no wonder that the wider world decided to add ‘B’ for boxer to the later flat-12 car, even though 312PB was not its official moniker. Here, we are only concerned with the 1969 V12 cars, and even though there were only three built and they raced for mere months, this hefty book in its slip case extends to 264 pages and as many photos.

Author Agnesa subtitles it “one of Ferrari’s most beautiful racers” and the line stands up proudly in a tough field. What’s pleasing to hear is that Enzo himself disliked the various performance-improving wings and flaps that at times spoilt its elegant lines – maybe it’s in Italian blood not just to appreciate beauty but to feel it matters.

Certainly it was the look of the car which hooked Agnesa all the way back in 1969, and though he doesn’t say when he started the book, it must have been a while ago as it includes reminiscences from drivers Chris Amon and Tony ‘A to Z’ Adamowicz, both some years dead.

Scrabbling for speed, two 312Ps were altered to coupés for the 1969 Le Mans 24 Hours

Motorsport Images

Despite working from the island of Sardinia he has managed to to speak to many significant people including the car’s designer Giacomo Caliri, who reveals much including that he incorporated aero lessons from his previous design, the Can-Am 612, which is why there’s an obvious resemblance. Rushed testing at a snowy Monza indicated that the sleek profile, kept clean to maximise top speed, was losing out in balance and downforce, so a chilled Peter Schetty was sent out again and again trying various aero add-ons. There’s a great shot of mechanics taping sheets of aluminium in place with snow lining the pitlane, a prime example of what makes this a feast for anyone who loves this period of sports car racing. Considering the three cars built entered so few races (and rarely finished – this was a luckless machine), there’s a wealth of fine images, of assembling, testing, racing and even of the filming of the Le Mans movie where one car featured briefly. That section includes an interview with Erich Glavitza, one of the driver-actors, who laments not buying the car at the time for its $30,000 asking price. Not quite sure if he need have included the bit about imagining stroking it and wishing it goodnight though…

“The author subtitles it one of Ferrari’s most beautiful racers and the line stands up proudly”

With its triple-language text (for us, Italy and Germany), sudden diversions into driver biographies, and wonderful whole- or double-page photos constantly arriving it can be a mite confusing to follow the tale, though in truth it would be a rapid read if condensed together. Following early promise and a slew of pole positions, the pretty machines constantly failed to deliver in what was effectively a single season as works entries, with second place at Sebring and Spa their best offerings in a spread of DNFs. A single car also made it here, coming fourth in the BOAC 500 at Brands Hatch with even more winglets attached to cope with understeer over the track’s undulations – which prompted Enzo to demand “What are those wings doing on the car?”. The winglets disappeared after that, although variations found their way back for the final works outing, a Can-Am race at Bridgehampton, USA – which was well out of view of the boss.

In an anxious search for extra speed, two cars entered Le Mans in 1969 transformed into coupés, and Agnesa carefully details the modifications needed to put a roof over the car’s head – including smashing four Dino 206SP screens while cutting them down. And, later in the paddock, engineer Caliri re-purposed a pair of Simca rear lights into brake cooling scoops; it’s the sort of detail people like me, more interested in the machinery than the results, will revel in. So be warned – if that’s not you, try another book.

Not that the author skimps the races. Each gets a lavishly illustrated chapter of its own, including pit panics and sad shots of crumpled bodywork leaning against walls. But the truth is that the project never fulfilled its promise. It was always going to be tough to turn essentially Formula 1 elements into a long-distance racer, and so it proved. Beset by a variety of difficulties from tyres to engines, the 312P never stood its ground against those pesky Porche 908s, while Ferrari was also throwing itself into creating the big-engined 512S to square up to the mighty 917. That effort would displace the smaller car from the squad for 1970, so two were sold to Luigi Chinetti Jr in the US while the third was used as a layout mule for the 512 before turning into Pinifarina’s ‘512 Special’ show car.

As ‘Coco’ Chinetti himself describes to Agnesa, the NART outfit managed to keep the sidelined design afloat for 1971 with much work, including giving it a square-cut body reminiscent of the works PBs, and later radically reworking it into what Agnesa calls “practically a new car” despite retaining the chassis number, to run at Le Mans in 1973 with one sad outing the following season before retirement.

You could point to some missing voices here, notably Mario Andretti who, with Amon, achieved a hard-fought second at Sebring, or David Piper who drove one at Le Mans in 1969, or David Franklin who has raced the one restored car in historics. There are a few translation quirks, nor is it cheap, but with its bold layout and McKlein’s fine quality imagery it’s a pleasure – as long as you like that sort of thing.