At home, I was a bit of a stickler for manners and courtesy. There was only one time I got the slightest bit cross with Justin. He was being such a prat over something, that I picked him up by his collar, pushed him against the wall, and told him to start getting himself together.

His mother was pleased that he had an artistic side but, at the same time, he thrived on speed, riding in motocross and competing in the British downhill ski championship in Wengen [Switzerland], crossing paths with the likes of Davina Galica.

He started racing much younger than me. I remember his first go on a circuit, which was at the Nürburgring, and I was driving a journalist around the circuit in my little Porsche 924 Carrera GTS. After a lap, the journalist had what he needed, and I asked Justin if he wanted to drive a lap. He drove it perfectly; I remember it so well, I hardly had to tell him anything and he had the lines and I knew, “Oh God, this is bad news…”

We were going to send him to the Jim Russell driving school, but then I possibly went a bit wrong and decided to coach him myself. We chose Bert Ray Formula Ford when possibly we ought to have gone with Van Diemen. My thinking was “I’ve been racing in Formula 3, Formula 2, even Formula 1; I’ve been at Ferrari, and I’ve had my first Le Mans win so surely I’m as good a person to teach him as any instructor?”

However, experience counts. By which I mean experience running a team, experience of raising money. So those that had better support from their team, or financially or in terms of management went on to get further up the ladder, even if they were no better a driver than Justin.

I only came to realise this in hindsight. And I think he should have done two seasons in Vauxhall Lotus rather than just one, because the first attempt you’re learning the car, the tracks, the team, and in the second year, you’re firing on all cylinders. On reflection, it was a bit of a mistake, but money was tight, and I was busy with my racing.

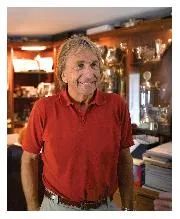

Achieving everything I did nearly didn’t happen. As I said, people talk about the good years, but they forget how much was bad. Grovelling around to keep your career alive. I had tea with Jimmy Clark the night before his fatal accident…

Ironically, when Jimmy died, it seemed to open up everything. Suddenly I had Enzo Ferrari wanting me, Colin Chapman, Cooper was onto me, and John Wyer was knocking on my door for Le Mans. How many drivers get four offers like that today – and I had to make decisions all on my own, without a manager or anyone like that? Yet by 1979, I was ready to quit racing and go back to working on the farm because I couldn’t get a drive.

To think Justin saw some of what I was going through and still wanted to go racing. People would say to me, and later to him, “When are you going to stop being a playboy and get a proper job, become an accountant?”

Justin Bell

Dad was a normal dad when he was at home. He’d take me to school or judo lessons, like any parent, and was hot on things like table manners and being courteous.

Communication was different then. From the family’s perspective, Mum raised us and was the disciplinarian. On the other hand, Dad’s gipsy-like life of travel meant once he left, we wouldn’t speak much. He’d call, but I remember him saying: “This is costing 50p a minute! I can’t speak long”. Back then that would’ve been extravagant. In the holidays we would go to races with Dad. I remember being woken in the middle of the night by my grandmother and being told someone was here to take me to Le Mans because they’d put the car on pole. It was when he raced with Renault, led most of it, and retired with engine trouble. [Derek drove a Renault-Alpine A442 with Jean-Pierre Jabouille in 1977.]

“I possibly went a bit wrong and decided to coach Justin myself”

The era they lived in was so savage. I can remember more than once dad sat on the edge of the bed in tears, mum consoling him, or going off to a funeral – he certainly went to a few. But I went through that too, saying goodbye to people like poor old Paul Warwick. [The younger brother of Derek died in 1991 after part of the front suspension on his Reynard F3000 car failed at Oulton Park.]

I was the creative one in the family. When I told Dad I wanted to try racing, I was doing a degree, and he said: “How the hell are we going to tell your mum?”

I hadn’t driven a kart when I decided I wanted a go at Formula Ford. Dad had me work on the farm, picking potatoes. I remember Tommy Payne would drive the tractor another 100 yards every time I’d gathered an armful with bleeding fingers and I’d say: “You bastard!”

My first single-seater experience was disappointing. We just drove up and down in a straight line and went around a few cones. I could see the circuit peeling off into the distance, and thought: “What the hell?”

Later, to be considered to be in dad’s world was an affirmation. He’s the most-liked human I’ve ever met, so it felt quite good when people wanted to talk to me, and I started to find my voice. But I’d argue that for people like me, Paul Stewart, David Brabham, we were more aware of the ultimate cost of racing over someone who fancied giving it a go. They hadn’t seen friends die, or their parents argue about dad being away, all that crap.

Where we’re similar is everything he’s ever done has been instinctual. So it was hard for him to explain to me how I should drive a Formula Ford. I moved quickly, switching up a category every year from Formula Ford to Vauxhall Lotus, and then I made a mistake when I should have stayed in Vauxhall Lotus for a second year, after finishing third in the championship, and then gone for the win. We also ran our own team; I was doing payroll at the age of 19 when I should have just been focusing on driving. It’s a lesson I’ll take with me to my grave, unfortunately.

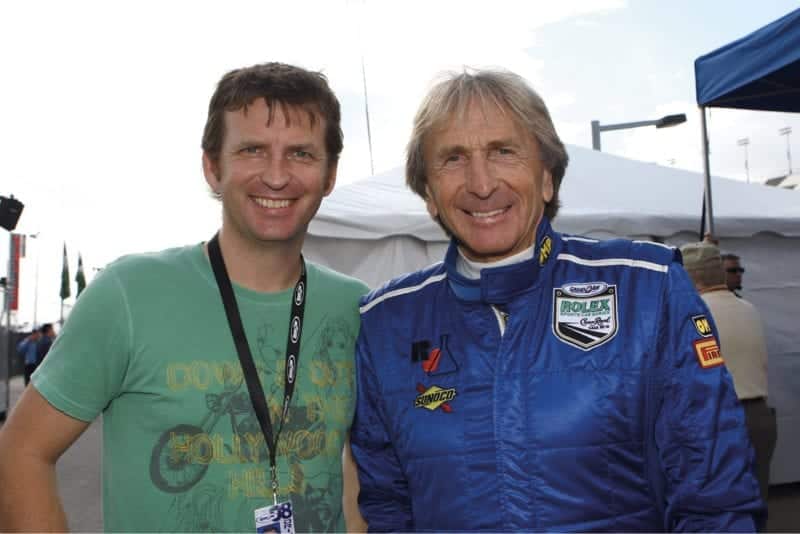

Then the money ran out, so I went to the States and won the Barber Saab championship. The prize money was fantastic for the time – you won $12,500 and to do a race cost $7500.

At that point, my cadence fell apart. I never had a strategy, it was all very reactive. I tried Indy Lights, which was a bit of a dump, just as British Touring Cars was blowing up. A lucky break came my way, though. After racing at Le Mans in 1992 with my dad and Tiff Needell, in a Porsche 962 which blew my mind, a friend hooked me up with a drive in a Viper Roadster at Le Mans with René Arnoux. It handled like a cheap leather sofa with an engine and a wing on it. However, it got me connected to Dodge, and I realised sports cars was the way I should go.

Then came Moody Fayed, and racing in the Harrods-sponsored McLaren F1 GTR with Andy Wallace. He was electrically fast at that point, and we raced it at Le Mans with dad, losing out on a win because of clutch trouble.

Justin headed to the States in a bid to emulate Derek’s successful sports car career

LAT

I didn’t quite work out all the elements of what I needed. I should have been fitter, more focused, and I kept forgetting to pay myself out of any deals I made.

When the Dodge factory drive came along it was the nirvana for any driver. Oreca transformed the Viper, and in 1997 I took the FIA GT2 championship. It led to a Chevrolet drive, and I could see 10 years of racing for Chevy. I pushed to drive in the number one Corvette, but there was a personality clash, which I wasn’t aware of, and at the end of the season I was dropped without any notice or explanation. I had never experienced a feeling of rejection and loss like that.

When I was racing, rightly or wrongly, I think dad always felt he had to justify me being there, or kind of make an excuse for me. He was so proud when I did well, obviously, but I think he carried the burden of me being his son more than I did with him being my father. I think he realises today that he probably didn’t prepare me terribly well for a career in motor racing, but at the same time he prepared me very well as a man for life.

I threw myself into my television career, and I think that today dad will happily tell anyone that I am the best at what I do on television. He knows that that’s who I am, and I’m pretty good at it and have that inner confidence in my abilities and that I know what I’m doing. It’s taken me a while, but I’ve finally found it.