OUTBOARD RACING

OUTBOARD RACING BY J. H. SHILLAN. (Mr. Shillan is already well-known to many of our readers as a successful exponert of the Elto outtoard motor. He is manager of the…

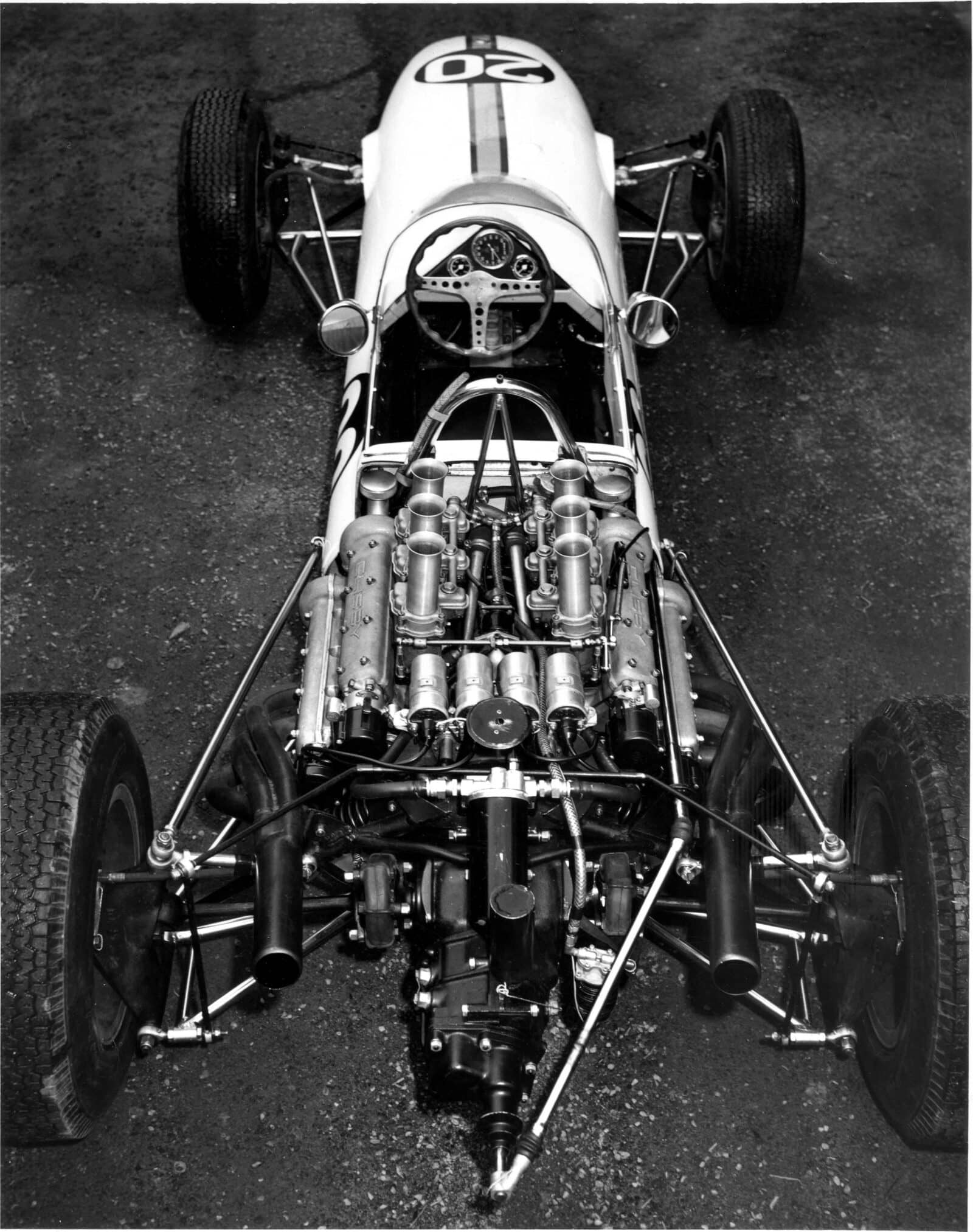

The Elfin-Clisby – Australia’s only entirely homegrown Formula 1 car.

Wildly eccentric yet immensely talented, self-taught engineer Harold William Clisby was responsible for Australia’s greatest racing might-have-been: a Formula 1 engine which could have beaten the Repco V8 to the punch by five years.

When the Clisby Industries 1.5-litre V6 finally made it to the track it powered the first and thus-far only all-Australian grand prix car: the Elfin-Clisby Type 100. Sadly by then it was 1965 and the 1.5 F1 formula was coming to a close. The car never made it to Europe or entered an F1 race. Too many other projects got in the way for the Adelaide engineer, including hovercraft, steam engines, an intricate model railway and the daily demands of his compressor manufacturing business.

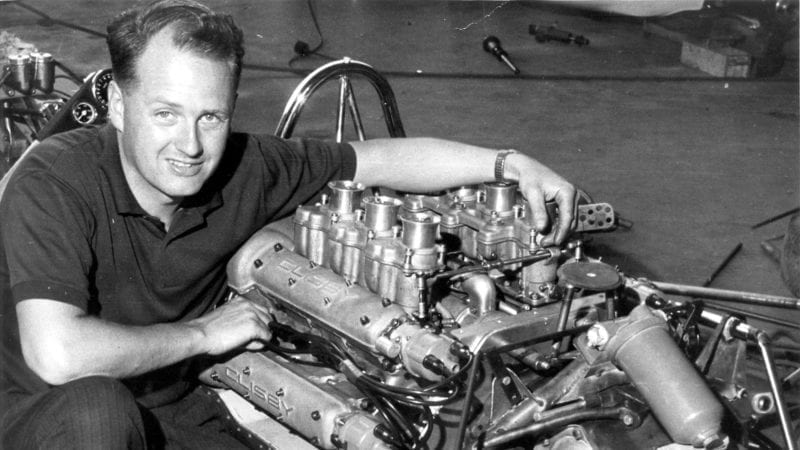

All was not lost. Clisby (below) learned enough in the process to later manufacture the cylinder heads for the Brabham-Repco BT24 that would win the 1967 F1 World Championship.

Now the largely unknown, Elfin-Clisby is coming to the limelight with a full-scale restoration and dreams of a Goodwood Revival appearance.

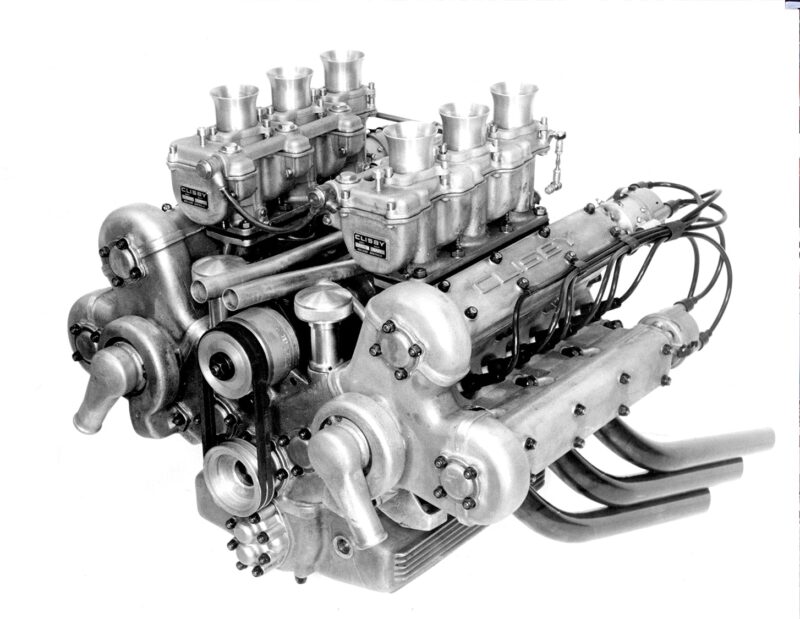

Let’s go back to the day the aluminium 120-degree, quad-cam, two-valve Clisby V6 hit the track. Key team members gathered for the first test of the car at the flat, tight Mallala airfield track 35 miles from Adelaide on Sunday March 14, 1965.

The group surrounding the little white, green and gold-striped car were a tad under the weather. The day before, the engine’s designer was married. The groom’s early start that crisp morning after was perhaps not what the bride anticipated.

Harold looked on paternally as project engineer Kevin Drage fussed around the car making last-minute checks, and the Dunlop tyre pressures were set.

Also there was ‘Mr Elfin’, the company’s founder and main man Garrie Cooper, an Australian cross of Lola’s Eric Broadley and Chevron’s Derek Bennett. Elfin Sports Cars was a family business he ran for 23 years which designed and built more than 250 cars, from grand prix winners to Formula Vees, and Cooper himself raced them at elite level, too. Mallala was Elfin’s home circuit; Cooper had raced and would deliver 19 of his T100 Monos there, named for their monocoque design.

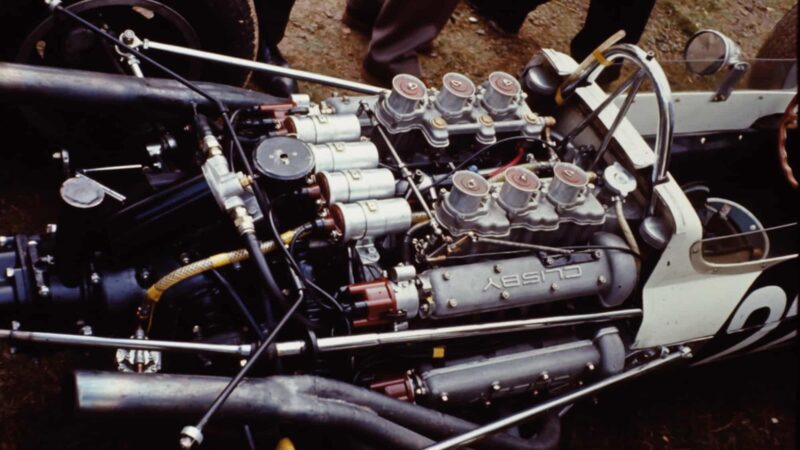

Quad-cam, dry-sumped design was a pure racing engine

Drage, the only member of the group still alive, becomes excited when discussing that day. He passed car owner and driver Andy Brown his helmet so that he could slip into the cockpit, but the wealthy industrialist and thrice Australian Grand Prix racer said, “It’s your engine.” “But it’s your car,” Kevin responded. “No, I insist you drive first.”

It was a wonderful gesture to the man whose persistence ensured the engine was finished and raced long after Harold had moved on to other projects.

Kevin’s hand clasped the throttle linkage of the Clisby triple-choke carburettors, the engine burst into life, and he gently blipped the throttle to 3000rpm before the motor settled to a rhythmic, gentle howl.

Drage slid easily into chassis M6548. First gear engaged with that characteristic ‘clunk’ of a dog box. With a cough and a splutter the car gathered speed towards the right-hander at the end of Mallala’s pit straight, but the national significance of the occasion was lost on Kevin whose nerve ends were jangling with every nuance of the car’s behaviour.

While the gearbox used a Volkswagen case, the five-speed transmission was made by Elfin. That was the amazing thing – the car’s engine, chassis, transaxle and other parts were all manufactured in Australia. Even the aluminium used for the chassis derived from Australian bauxite.

“The engine, chassis and other parts were all made in Australia”

Brown then climbed aboard, and was impressed by the punch of the engine compared with his Ford-powered Elfin Catalina. After completing six laps he pulled in. Kevin recalls, “The engine idled quickly and then suddenly started to vibrate so much that the rose joint on the rear anti-roll bar disintegrated, then the engine stopped. I pulled off a distributor cap. The vibrations had shattered the rotor to powder!”

Another great engineer was present. Eldred Norman, a friend of both Harold and Andy, questioned Harold and determined that while the engine was in static balance, the crank had not been dynamically balanced. “No problem, I’ll see you tomorrow morning,” said Eldred. “Just have the crank drawing ready for me to look at.”

“Sure enough, Norman called at the factory, a converted stately home, and worked out where balance weights were needed,” Drage affectionately recalls. “We modified the pulley to drive the dry-sump pump and we rebalanced the flywheel. I never got a photo of the jig-borer located in one of the big rooms underneath a huge chandelier, but the sight of it always gave me a chuckle.”

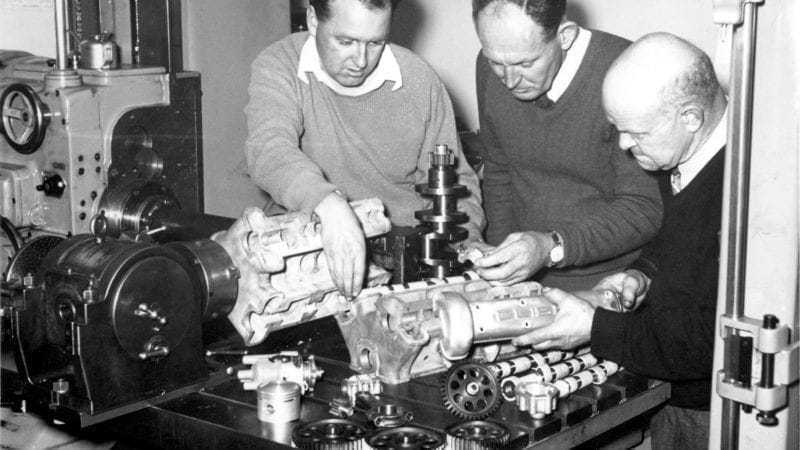

The creators – Harold Clisby, Kevin Drage and Alec Bailey with part-assembled V6

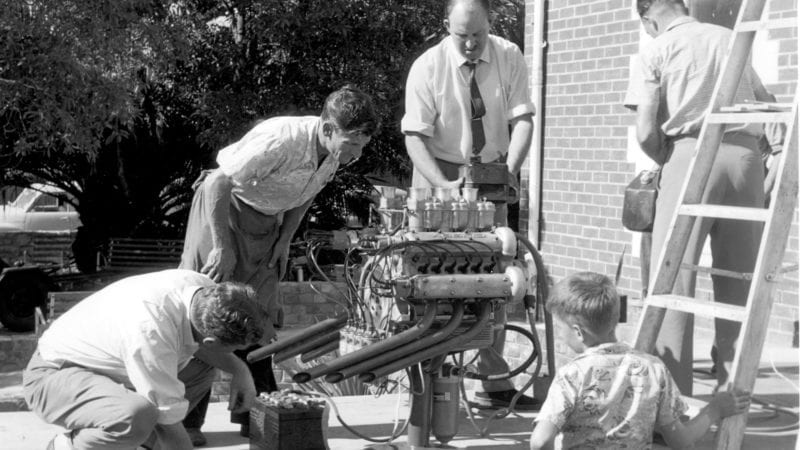

the very first firing up of the engine behind the factory, with Harold Clisby on throttles, Kevin Drage kneeling, and total-loss block cooling by means of garden hose!

The team discusses how to assemble the brand-new engine components

While work proceeded in Adelaide on the V6, in Melbourne Repco’s F1/Tasman V8 fired its first shot in anger on March 26, 1965. Highly respected motor-cycle/automotive engineer and author Phil Irving commenced his engine, expedited by the use of an aluminium Oldsmobile F-85 production block in early 1964, whereas Harold got things going on his bespoke unit aboard a ship back from Europe in October 1960. Fired up by visits to Coventry Climax, BRM and Ferrari, Clisby had decided to build an F1 engine. How hard can it be, after all?

While a 1.5-litre V6 was state of the art in 1961, it was a dinosaur in 1965. Ferrari had won the 1961 F1 titles by catching other teams napping, having built its first Formula 2 1.5-litre V6 in 1956-57. By late 1961 Coventry Climax and BRM had V8s which dominated in 1962. Colin Chapman raised the bar with his super-stiff and slinky first modern monocoque Lotus 25, while Honda and Ferrari raced 12-cylinder cars. None of this mattered to Clisby, who marched to the beat of his own drum; his factory cellar was full of part-completed projects.

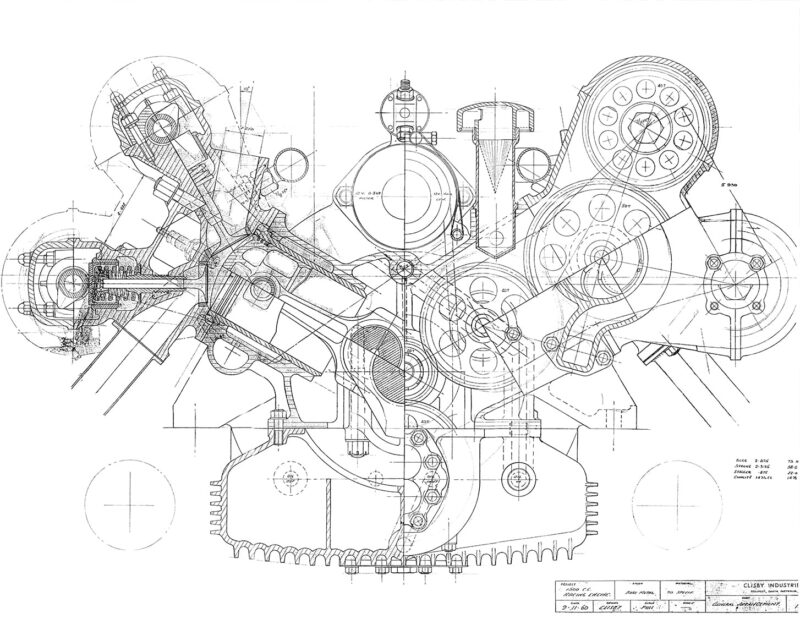

“Harold didn’t have much formal education, but he was a brilliant intuitive engineer,” says Drage. “He had an innate feel for it, excellent recall and was a great draughtsman – he drew the whole engine.” Alec Bailey did most of the complex machining with Kevin as project engineer.

“A Dunlop blew at high speed removing the rear suspension”

Harold’s projects were a journey. Designing and building them in-house was what mattered most to him, rather than getting an engine onto the grid quickly. Production of the steel crankshaft was a case in point.

“Harold was careful with his pennies,” Drage observes drily, “and would rather do something in-house than go outside. De Havilland in Sydney could have nitrided the crank but Harold built a nitriding furnace and increased our foundry capacity to cast internally instead. We lost heaps of time like this. We had no deadline and had routine projects to complete. This was a big part of the reason for the V6’s long gestation period.”

Clisby Industries was small, too: the headcount was only 17, churning out 100 compressors a week among whatever else took the imaginative owner’s fancy.

“Even simple things became problematic. The wide engine precluded the use of tripledowndraft Webers, but a pair of Weber triples made for Ferrari’s 120-degree V6 would suffice. We ordered them and received a letter from Ferrari’s lawyers claiming proprietary rights to the carbs and 120-degree V6 layout! It didn’t worry Harold, though. We designed and cast carburettors which used Weber jets and air-bleeds, but that exercise also took plenty of time.”

Kevin Drage fettling the new motor during an early test at Mallala experimenting with tall intake trumpets

Roll-out of completed car at the Elfin factory following engine installation in modified T100 monocoque

Ready for first test at Elfin, Edwardstown with temporary stack exhaust, showing the Elfin Mono’s pushrod suspension

Press interest started in the April 1961 issue of Australian Motor Sports and Automobiles. Sports Car Graphic in the US followed and Britain’s Motor Racing in December 1962. In Motor Sport in 1963, Denis Jenkinson suggested that Jack Brabham “might be patriotically inspired to try a Clisby V6”, but Drage downplays that. “I’m certain Harold had a phone discussion with Tom Hawkes about using the engine in his proposed Ausper F1 car,” says Kevin, “but I’m equally sure he never spoke to Jack Brabham about its use.”

Drage discussed with four-time Australian Grand Prix winner Lex Davison funding an Elfin Mono, but simultaneously Andy Brown spoke to Harold, leaving Drage with the embarrassing task of “telling Lex we could not proceed with him”.

In Calder paddock, showing how the compact V6 fitted neatly into a space originally designed for a four

Harold lost interest as time marched on, though not before scheming a two-stroke 3-litre F1 engine, but at Elfin, Cooper was making progress modifying the monocoque and rear suspension to accept the engine. The potent little combination was finally ready and entered for the April Mallala Easter meeting.

A staggering crowd of 20,500 turned up, with plenty making the trip just to see the exotic home-town Elfin-Clisby. Andy warmed up the spectators by blipping the throttle to 5000rpm but the 20-lap feature proved a fizzer when Brown had a Dunlop blow at high speed on the curved Back Straight, removing the Elfin’s rear suspension in the process.

With the car repaired, the small equipe headed for the short one-mile Calder circuit on Melbourne’s outskirts for a round of the Lucas-Davison 1½ Litre Championship on May 23. Brown qualified well, mid-grid alongside future Brabham racer and F1 points-scorer Tim Schenken’s Lotus 18. Despite pouring rain and resultant gentler throttle applications the engine developed a misfire.

“We then ran the engine on Jack Hunnam’s Melbourne dyno and the misfire was traced to coolant leaking through porous head castings – a major problem we had to solve,” Drage ruefully recalls. “We rebuilt the engine with new heads and set off to Mallala in June but the Elfin’s South Australian Road Racing Championship meeting was over before it started when it popped an oil-line in practice. It was a massive disappointment; luck seemed to be against us.”

The machine finally started an Australian Drivers’ Championship round at Mallala on October 11. Bib Stillwell won that race in his Brabham-Climax while Andy had the engine lock solid on the main straight after only eight laps, gyrating from side to side and coming to rest gently in the dusty infield. With that, the single engine built was set aside.

Once Clisby’s interest had switched to new projects, it was Drage’s efforts that saw the V6 through

“Any chance of contesting ANF 1½-litre events was firmly scuttled when CAMS [Confederation of Australian Motor Sport] told Harold the engine wasn’t welcome among the twin-cam Lotus fours. It was impossible to increase the engine’s capacity much, so a Tasman motor wasn’t feasible either.”

It wasn’t an ignominious end for Clisby’s racing connection: there’s an F1 epilogue through Clisby’s role in the Brabham-Repco BT24 ‘740’ V8’s 1967 championship wins.

On regular trips to Melbourne, Drage called on Phil Irving. In mid-1966 he swung past Repco-Brabham Engines Pty Ltd to find Phil had left after a disagreement with Frank Hallam, RBE’s boss. “After Hallam conducted my factory tour, I showed him some quadcam Ford heads we made. He wanted timelines to cast their 1967 heads, and ours were less than Sterling Metals in the UK who had made the 1966 heads, so we got the chance. I was over the moon!”

Clisbys produced Repco’s 30, 40, 50 and 60 Series heads, over 100 in all, which played their part in winning the manufacturers’ and drivers’ championships for Brabham and Denny Hulme in 1967. Repco’s 1967 titles would not have occurred without what Clisby had learned in preceding years.

Only known shot of Elfin-Clisby racing: Andy Brown, Calder Raceway, May 1965 – before misfire

The Clisby V6 engine was housed at the Sporting Car Club of South Australia. On one occasion, before giving a presentation to members, Harold started it up among the Victorian oak-panelled splendour – imagine a works Stratos firing up in your local pub! The Elfin chassis was fitted with a Cosworth- Ford engine and raced on.

“Various enthusiasts dreamed of reuniting the car and engine until Adelaide’s Peter Bail obtained Clisby family support to use the V6 on loan, which allowed the chassis purchase from its long-term owner,” recalls the car’s current custodian, Australian Elfin enthusiast and racer James Calder. “The engine agreement was later rescinded, so in 2015 Peter sold the project to me.”

Detective work over a decade allowed Melbourne-domiciled James to purchase unused engine components auctioned when Clisby Industries was sold. These comprised an unmachined block, heads, gear-case, camcovers, crankshaft and rods as well as patterns and moulds. Calder has progressed the chassis and engine ancillaries with the assistance of Drage, who is as sharp as a tack and “still on the right side of the turf”, as he puts it, at 85 years of age.

The task is huge, with teenage kids and growing global business distractions, but James is determined. “The dream is for Australian Gold Star champion John Bowe to run the Elfin-Clisby in the Goodwood Revival meeting soon,” James says with a huge smile – clearly delighted at the prospect of the car running again after 55 years.

The Elfin-Clisby is a footnote in Formula 1 history, but the Repco 740 engine was a world champion. There is a familial link between two engines conceived and built more than 450 miles apart, and of that, Harold Clisby, Alec Bailey and Kevin Drage were, and are, very proud.

Harold Clisby was born in Adelaide in 1912. At age seven he was given a Meccano set and a lathe to keep him out of the workshop – and a life of engineering was away.

In 1938, having built his first cars, he left the family business and joined Litchfield Engineering, which made model aircraft engines like those he had been building and selling.

In World War II, a General Motors-Holden senior engineer noticed the self-constructed gas producer on Clisby’s car and offered him a job. He progressed to project engineer.

Post-war he saw an opportunity to build air compressors, products that Clisby Engineering constructs to this day.

Harold Clisby aboard his self-built Douglas-engined hillclimb special in 1952

Harold first raced an MG TC at Nuriootpa in 1949. He helped lay out Collingrove Hillclimb, then built the Clisby-Douglas Spl in three weeks to contest its first meeting, winning his class and setting a record in the process.

He built his own ‘castle’ in the Adelaide Hills (above) with a model railway traversing its grounds, and there were two hovercraft, and much more…