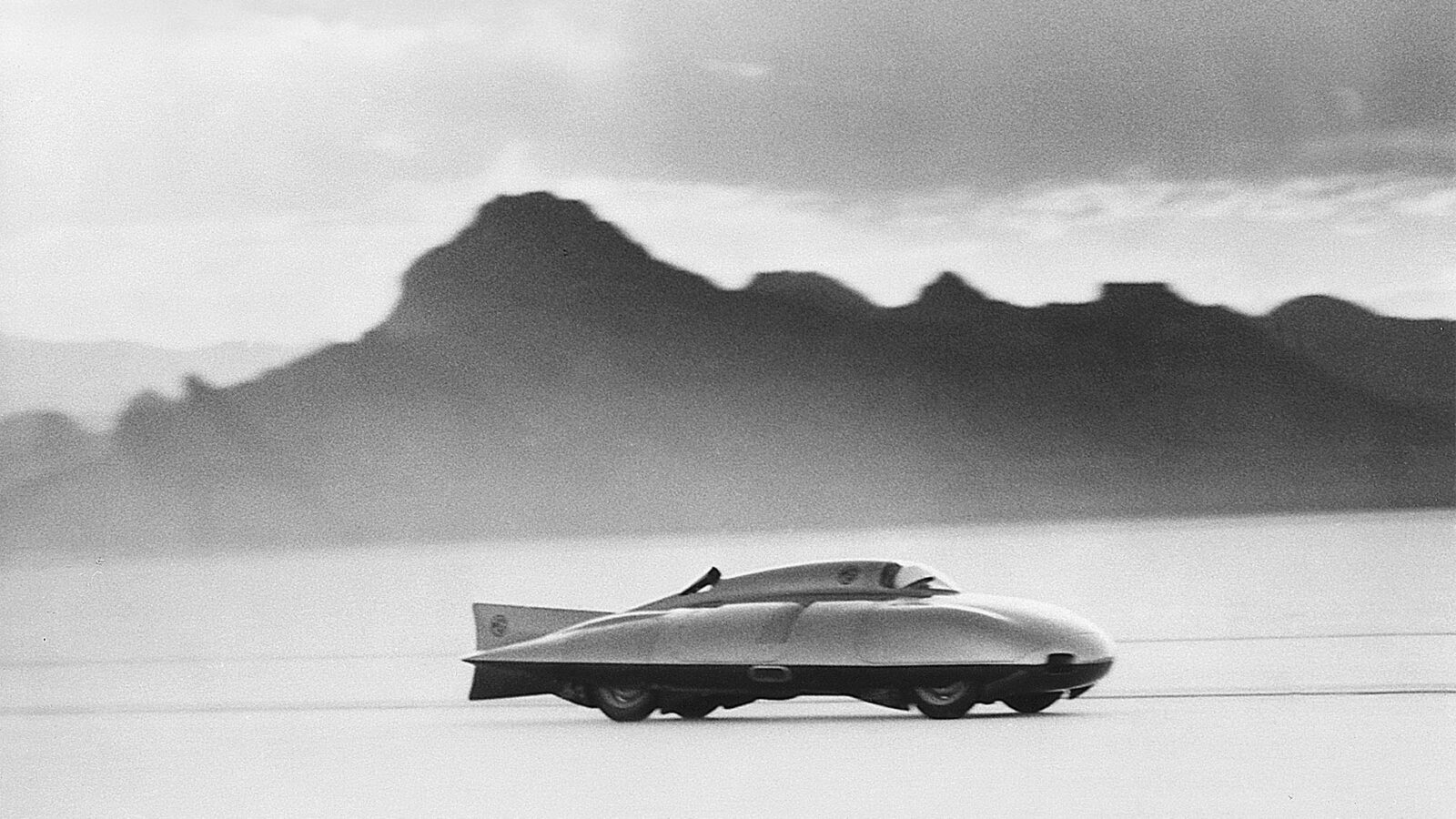

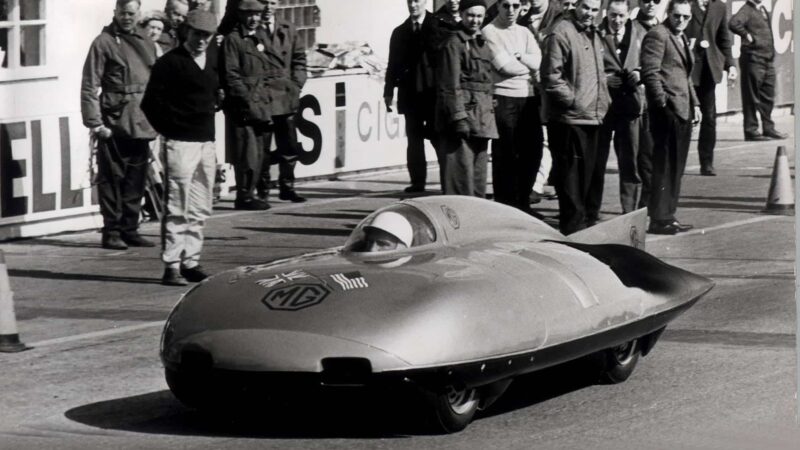

Apparently its drivers didn’t have any great concerns in this regard, otherwise Stirling Moss would not have been able to set his 1957 record (245.64mph for the flying kilometre, 245.11mph for the mile) in a short timescale between racing commitments, and Phil Hill would not have been happy at the tail being removed for his runs in 1959, which culminated in a best of 254.91mph for the kilometre and 254.53mph for the mile.

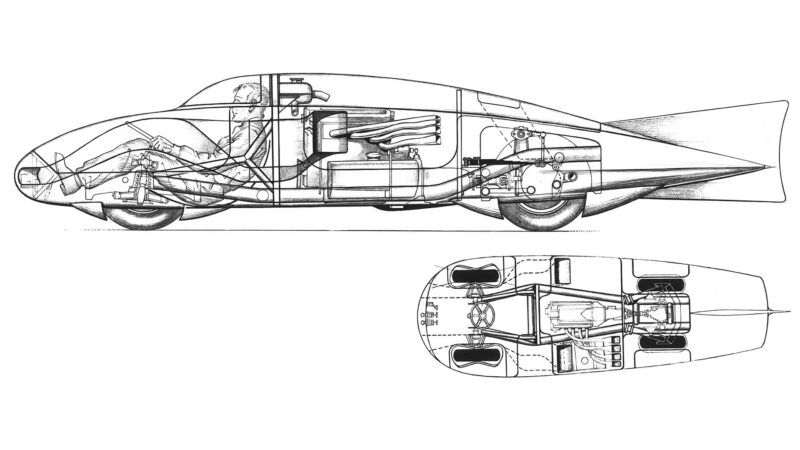

Just how efficient the EX181 was at cleaving the air is not clear. If we accept a frontal area said to be 10 per cent less than the EX179’s 11.8 sq ft then figures of 145bhp for 200mph and 240bhp for 245mph suggest a drag coefficient of about 0.24 – too high for a body form like this, which ought to be capable of 0.15-0.20. So these figures probably include transmission losses and/or rolling resistance.

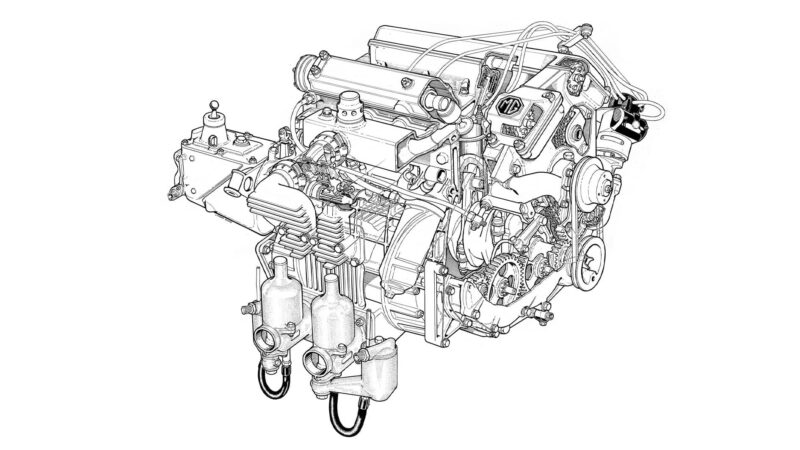

A factor contributing to Hill’s higher speed in 1959 was the fitment of an engine bored out from 1489 to 1506cc, which MG deployed to exceed the 1500cc limit of class F and so place the car in class E (up to 2000cc), thereby increasing its tally of records rather than supplanting those it already held. Most obvious of the many differences between the road-going engine and its record-breaking cousin was that the latter sported a massive Shorrock supercharger, driven by spur gear from the front of an extended crankshaft, which sucked air and fuel mixture through a pair of 2.5in SU carburettors. Blown at 32psi the 1957 engine reportedly delivered some 290bhp at 7300rpm – 195bhp/litre – and 516lb ft of torque at 5600rpm, with the spare engine capable of a little more because of a slightly higher compression ratio.

Profile based on aerofoil

Developed by Eddie Maher, the supercharged twin-cam four-pot had a prodigious appetite for the equal parts petrol/benzol/methanol that was its diet, as Basil Wales – who worked on the engine as an apprentice at the Morris Engines Experimental Department in Coventry – recalls. “We had to put in a special fuel supply that we could replicate in the car. Almost by chance this ended up as a compressed air bottle, with a reducing valve, to pressurise the fuel tank. We put some needles in the twin SUs, started up the engine and it promptly backfired. We lifted the dashpot and it ran a bit better, showing that it needed a richer mixture. So we took the needles out of the carburettors, put them in a lathe, filed them down and tried again. We had to go through this process quite a few times before we could get the engine running properly. Then we got some pretty good results from it early on.”