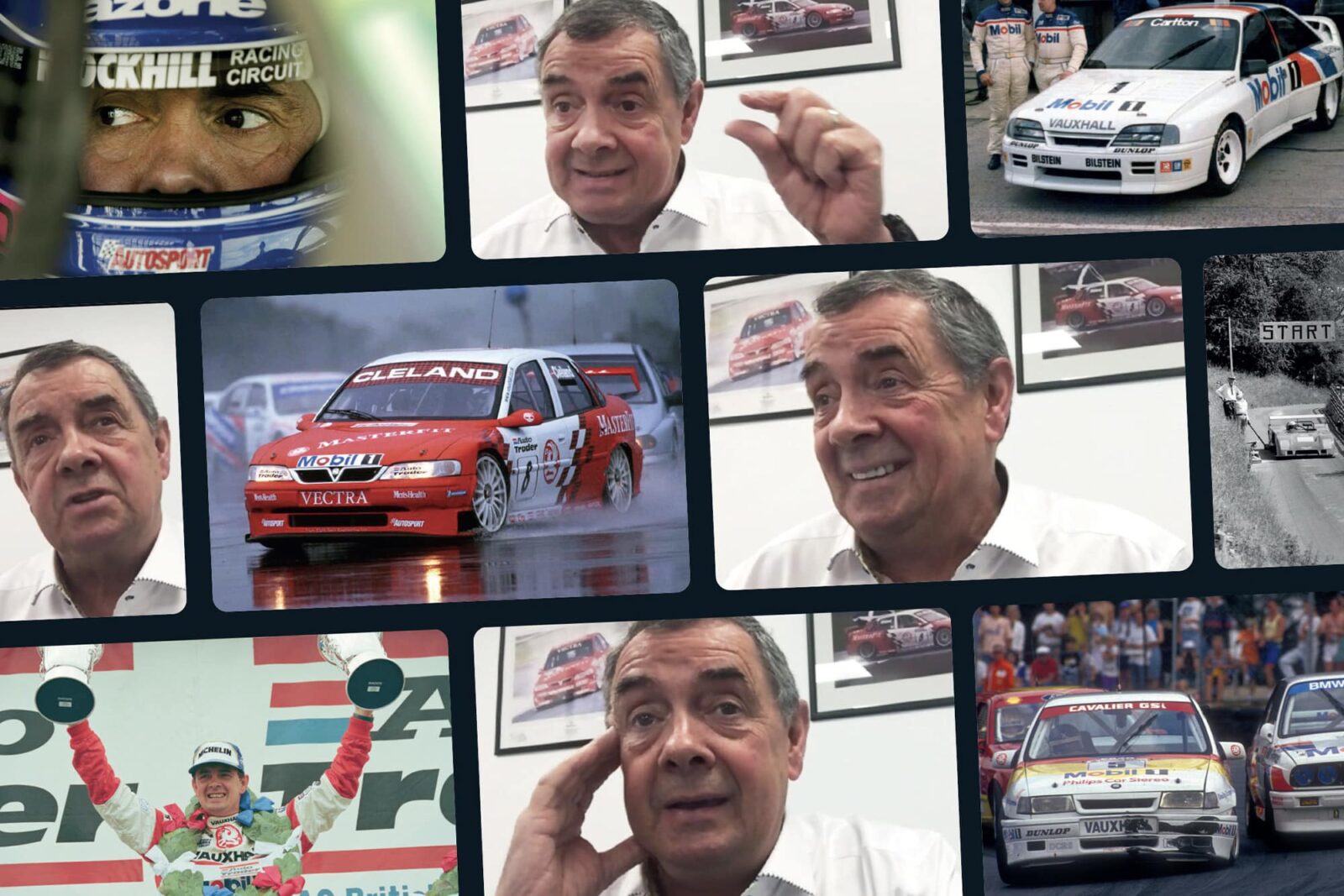

Virtual Lunch With John Cleland

He has beaten ex-Formula 1 stars and Le Mans winners alike, without ever deviating from his roots as a car dealer in the Scottish Borders. John Cleland reminisces with Simon Arron

The best-laid plans… Motor Sport originally intended to catch up with John Cleland in March, but a minor cough triggered a postponement – “My wife put me in quarantine, to be on the safe side” – and pubs and restaurants locked their doors before we’d had the opportunity to reschedule. In the end a compromise was reached: the 67-year- old Scot would become our first ‘virtual’ lunch – we’d have the conversation via the miracle of an internet video call, then buy him the real thing as soon as practicable. “I’ll settle for a sandwich and a bag of crisps while I’m waiting,” he says, before settling down in the office of the Volvo dealership he manages in Galashiels. Conversations such as this usually take place from a distance of about three feet, but in this instance, the degree of separation is closer to 370 miles.

An interesting case, Cleland. He was at the hub of a touring car racing boom in 1990s Britain, when manufacturer teams arrived in droves, bringing with them a pedigree cast of tin-top specialists and single-seater or sports car converts. The racing was spectacular, the budgets even more so. In a world of ever greater professionalism, the Scot was something of a throwback. While many of his peers were free to focus on their sporting craft alone, win or lose he would usually be back at his desk at 8.30 on Monday morning – his focus adjusted from racing cars to selling them.

But that’s how his life had always been. “My father Bill was the first member of the family to take an active role in motor sport,” he says. “He was a car dealer during the week, but he was also the RAC’s chief scrutineer in Scotland. When I was six or seven, I’d be bundled into a car and we’d head to Bo’ness, Doune or wherever. I’d wander about while he was doing the scrutineering, so I kind of grew up around motor sport.

“Because he was a Triumph dealer, I was sent to do my apprenticeship in Coventry with British Leyland and did my first competitive event in April 1971 – a Triumph Automobile Association autotest in the company car park, at the wheel of a Herald. It had those silly back wheels that waved around, but it was a means to do something.

“I’d always wanted a kart, but Dad would never buy one. He eventually took one in part-exchange – a gearbox chassis with a Bultaco engine. All I remember about that is being towed up and down the main road, behind a Lotus Cortina, trying to get the thing to start, but we never succeeded!

Where it all began: John makes his racing debut in a Mini at Ingliston in August, 1972

“After finishing my apprenticeship, I went back home, and part of the deal was that Dad would buy me a Mini. I had to find the money to run it and then repay him for the car at the season’s end. That was a hard way to do it, but we always seemed to make a profit. The first proper event I did was in 1972 – a hillclimb at Kinkell, which ran through a caravan park near St Andrews. I’d bring the Mini home, and it had these trumpet things in the rear suspension, so you could raise the ride height, and then we’d bolt on a sump guard and go out the following weekend to do an autocross. Then we’d lower it again, and go off to do another hillclimb or a sprint. That’s how it was for my first two or three years, when Minis cost about £400 apiece, there wasn’t a lot of money in them.”

You might notice that there isn’t much mention of racing. “No,” he says. “As a scrutineer, Dad had seen many accidents, and he’d also been friendly with Jim Clark. I think he had the attitude that getting involved in racing would mean hurting yourself, so I wasn’t doing that as far as he was concerned. It took me virtually the whole of 1972 to convince him that I should enter a race and I did just one, that August at Ingliston, where I finished fourth – again in a Mini.”

Cleland hillcimbed a Chevron B8 in 1973 (bought for £1400 and sold for £2000) – and profits from that were reinvested in an ex-Red Rose Racing Chevron B23 (“Dad gave the seller a Reliant Scimitar and a bag of cash”). The focus, though, remained on speed events, with the dispensation to contest one race per annum. “No matter how good I was in hillclimbs – and with the B23, I’d be up there against the top 10 run-off guys with their DFV-powered single-seaters – he still didn’t want me to race, for safety reasons.”

Cleland in action at Doune in 1974, driving a Chevron B23

Cleland Sr had retired from the full-time car trade at the end of 1972, but decided to resume in ’76 and run a Mitsubishi dealership: for John, that was a trigger to prepare a Colt Lancer for the Scottish Rally Championship. “It was a fairly standard thing, just 1600cc,” he says. “I finished all 10 events, but I might be the only person to have received a letter from the Forestry Commission asking me if I could stop rallying, because I think I was knocking down more trees than they were!

“Every time we got near asphalt, it was great – I was there, on the pace, catching people hand over fist, but in the forests, I was pretty s**t. It became quite obvious that I wasn’t really cut out to be a rally driver, but it was the only way I’d been able to do any events. I did get some class wins, though.”

With his dad switching loyalties from Mitsubishi to Opel, John’s next competitive project was a Kadett GT/E, again primarily for the hills, but a change in attitude was just around the corner. “I think Dad realised that I could drive cars of the kind I was using, and when I did the odd race I wasn’t getting involved in any scuffles, so he was prepared to let me do a bit more. Whereas he was initially against the idea of me racing, he would go on to be my biggest fan and push to find things for me to drive.”

Cleland began to star in production saloons in the early ’80s, racing against Gerry Marshall, Tony Lanfranchi and other national racing royalty. “This was my real introduction to the circuits,” he says. “I was up against guys who had done millions of years of racing, and I learned a lot. There was a lot of close competition, a preamble I suppose, to what we’d later see in touring cars – door mirrors would disappear, bumpers would hang off – but it was an interesting learning experience. For 1980, we’d prepared an Ascona i2000 – a 2-litre, two-door saloon. Opel assured us that they’d get permission to homologate the car, but they didn’t. I won my third race in it at Mallory Park, but Gerry Marshall protested and I got thrown out. I then went to Ireland and bought a Commodore from Frank O’Rourke, whom I’d met over there when racing the Kadett, and spent the next two seasons in that. I won a few races and set a few lap records. I remember going to Thruxton for the first time in 1980, and Gerry telling me that I’d be lucky to qualify in the top 12, given my lack of track experience. I promptly stuck it on pole, which shut him up. It was my kind of track, fast and flowing, though I ended up only fifth in the race.”

He would remain in production saloons for the first part of the decade, graduating from the Commodore to a Monza. In 1982 and ’83 he shared a Monza with Lanfranchi in the Willhire 24 Hours at Snetterton, Cleland’s future BTCC rival Steve Soper alongside them on both occasions. “That was the first time I’d met Steve,” he says. “and I found it useful to be able to measure myself against a pro like that. I proved to be pretty competitive, but at no stage did it ever occur to me that I could make a living out of this. I was a car dealer who enjoyed raising a bit of sponsorship to do what I wanted to do at weekends. Every Monday, I’d be back in the office again selling cars. I should maybe have stuck at it properly… That said, I always wanted to keep the dealership going because I knew it would be important to me one day when I didn’t have any motor sport, but I didn’t know when that was going to be. At that stage I’d still been paying for everything myself, but in 1984 I formed part of a three-car production saloon team with Gerry and Tony – and the following season I got a bit of money from Opel, which was a leg-up to doing a bit more with them.”

Cleland (right) with ex-F5000 racer Steve Thompson at Mallory. The duo drove the ‘Senator’ in its first test in the UK

It was a brash decade for the sport. Formula 1 was in its turbocharged pomp, John Webb – then head of MCD, which controlled Brands Hatch and its affiliated circuits – had introduced Thundersports, which allowed relatively recent Can-Am cars and suchlike to be set loose around Oulton Park and Snetterton, and Thundersaloons fulfilled a similar role in the world of tin- tops. It was here that Cleland moved in 1986, sharing Peter Brock’s ’84 Bathurst 1000-winning Holden Commodore V8 (rebranded as a Vauxhall Senator for the domestic market) with experienced saloon racer Vince Woodman. Running in official GM Vauxhall Dealer Sport colours, they won the title before switching to a V8-powered Vauxhall Carlton with Kevlar body panels and an estimated 600bhp. Reliability problems capped their ambitions in ’87, but one year on they were champions again.

“Vince had a fine reputation,” Cleland says, “but I was capable of outpacing him most of the time. I shared the Carlton with Derek Bell for one race at Donington, too, and was every bit as quick as he was. I should have realised that I could go on to do something a bit different, but it honestly never occurred. If I’d got in the Commodore and Vince had been two seconds faster than me, I’d have had to step back and say, ‘OK, fine, I get that. I’m clearly useless at this.’ But it was proof that I could do it.

“At about this time, I was also watching the BTCC quite closely. It still had the multi- class system then, and the champion often used one of the smaller cars – as Bill McGovern had done when it was still the British Saloon Car Championship, ditto Chris Hodgetts more recently. I pounded the guys at Vauxhall to do something with the Astra GTE. They were rallying the car, so already had the gearbox, engine and suspension, and they were doing pretty well in those days, with Malcolm Wilson and Louise Aitken- Walker. All they had to do was hone it a bit, give it to somebody like Dave Cook [the race preparation specialist who had built the Carlton, among other things] and they could theoretically beat the VW Golfs and so on in that class to win the championship. Initially, the response was negative, but I was very persistent, and eventually, they relented.”

This was long before the three-races-in-a day, 30-per-season format that has become the championship’s staple. There were 13 standalone events and Cleland won his class 11 times – though the destiny of the 1989 title was undecided until the Silverstone finale.

“It ended up being a straight fight between James Weaver and I – the first sign that I’d spend much of my touring car life battling against BMWs. Although I came out on top [both drivers won their class that day, Cleland taking the title by one point], and held the trophy that Jim Clark had won back in 1964, I felt a bit as though I’d cheated because I’d usually finished about 15th overall. I’d been there running two thirds of the way down the field, racking up points, but I couldn’t see how that was right.”

The championship slimmed down to two classes in 1990, with the new 2-litre category [Super Touring, as it would become known] forming the support act as the Ford Sierra RS500s performed their flame-belching swansong, and Cleland was part of the Vauxhall factory team, taking his Cavalier to fifth overall, second in class behind Frank Sytner’s BMW M3. When the single-class structure was implemented the following season, Cleland took four wins, more than any other driver, but Will Hoy’s superior consistency earned him top spot over the campaign’s course. “I loved racing Will,” Cleland says, “and had massive respect for him, as I did for many of the others over the years. We had some fantastic battles, side by side, and I knew I could trust him. I wouldn’t have climbed in a car with some of them for a lift to the pub.”

BTCC infamy: Soper and Cleland clash in ’92 title decider at Silverstone, but later became close friends after an MSA tribunal

Jakob Ebrey

It’s hard to believe 28 years have passed since, but the 1992 BTCC season remains a popular conversational trigger. The tale has been recounted many times, but Cleland was in the title fight throughout the year until being eliminated from contention late in the Silverstone finale, after a collision with Steve Soper – team-mate to title rival Tim Harvey.

“I’d had a huge shunt during testing at Donington Park, breaking my sternum and my lower back,” he says. “I still had to do Donington and Silverstone to challenge for the championship – and had I not been leading it all year, I’d probably have gone home and taken three months off to recuperate. Despite the pain, there was no way I was giving up. I was lying in a Derby hospital for a couple of days, while they worked out what to do, and my mobile rang. It was Keith Greene, who’d be running the new Renault team in 1993. He asked whether I’d be interested in partnering Alain Menu, but at that stage, nobody knew what the Renaults would be like, and I had a good offer on the table from Vauxhall, so I declined.

“I turned down a drive in the car that beat me to the title!”

“What very few people know is that I’d also been offered a seat in a Vic Lee BMW for 1992, effectively what became Tim’s car. Vic pestered the life out of me during the winter of 1991 – I don’t like what he did [Lee was later convicted of drug trafficking], but I admired him as a team owner. But I’d have been alongside Steve Soper, and he was BMW’s man, so it seemed logical that he’d be their favoured driver. Vic assured me that I’d be given equal treatment, but eventually, I decided not to do it… and thus turned down a drive in the car that beat me to the title!

“I always thought it had been Vic trying to get me in his BMW – it was many, many years after that, when Steve and I were having a conversation, that he informed me that it had been BMW in Munich who’d wanted me. Had I known that at the time, I would have taken the deal. Vauxhall was great in touring cars, but BMW was a global motor sport player and Steve went on to do Le Mans, for instance. Perhaps I could have done something similar, but I didn’t know the impetus was coming from BMW.

“In that final race, I knew exactly where I was and what I had to do. I was running behind Will and Tim, and that was fine for me in championship terms. It was all going swimmingly because Tim flicked Will off at Copse and Steve had been binned during the early stages, so I wasn’t expecting to see him again, but then he reappeared on the scene. As soon as he got between Tim and I, it was no good for me. When I re-passed him at Brooklands, I thought it was quite a good move, I know it looked dramatic [the Cavalier was well up on two wheels at the critical moment], but I didn’t squeeze Steve onto the gravel at the exit. My mistake was to allow him enough space, and as I turned into the next right-hander, biff. That was it.

“Afterwards, the Motor Sports Association [now Motorsport UK] wanted to hang somebody out to dry. We were summoned to a tribunal and had to employ barristers. The night before, I phoned Steve at home and said, ‘Listen, this is silly. They want someone’s licence, and I suspect it will be yours because, let’s face it, you drove into me.’ I suggested we went in and said the same thing, that it had been an unavoidable racing accident. Initially, he said he didn’t trust me, so I agreed to talk first so long as he backed me up. We made our statements and Win Percy, the driving standards advisor, had steam coming out of his ears. As a professional racer, he knew what we were up to, but the case was dismissed with nobody to blame, just a racing incident.

“It put the BTCC on the front page of everything, heightened the championship’s profile, and whether I won or lost the title doesn’t matter now. Without that I’d have been a triple champion, but who gives a f***? It’s history.”

Cleland and Soper subsequently became good friends – and remain so.

Cleland finished fourth in each of the following two seasons, during the second of which Vauxhall’s cars were run for the first time by Ray Mallock Ltd. “Ray took over the Vauxhall deal from Dave Cook, and I’m sure he wanted his own drivers in there,” Cleland says. “I think he regarded me as a joker because that’s how I was in the paddock, so I had to convince him that I was serious and that I’d drive the socks off the thing when I got in. Perhaps it went against me that people perceived me that way, but during my time in touring cars, I received offers from every manufacturer other than Honda and Peugeot, the latter of whom I wouldn’t have driven for anyway.

“I was doing this because I was enjoying it. Even when Vauxhall was paying me pretty good money, it was still a bit of fun. As soon as I climbed in the car, though, I had only one target. If you wanted to put something on my tombstone, it would be ‘Never give up’. That was my ethos. It didn’t matter where I was on the grid; anything could happen in front, so I could still win. That was my mentality.”

With the Vectra on the horizon, 1995 would be the Cavalier’s final season, and it proved to be some swansong. “After I drove the new version for the first time, I told the team to wash it, put it in the truck and take it to the first race… and that I’d be able to win the championship,” Cleland says. “That’s how confident I felt.”

It was justified. He won the opening race of the year at Donington Park, added five more victories and finished on the podium in 18 of the 25 races to clinch his second BTCC crown. “At the end of the year,” he says, “Audi team manager John Wickham called to see whether I’d be interested in teaming up with Frank Biela in ’96. I told him I’d love to, but that I was halfway through a two-year deal. If we wanted to get messy, I had no doubt that Audi’s solicitors could extract me, but I’m a man of my word and couldn’t un-shake somebody’s hand. Frank went on to win Le Mans with Audi what, five times? He’s a few years younger than me, but who’s to say I might not have had a crack at the race if I’d signed that deal? It’s one of the things I never did. I went there with a mate in 1976, no special passes, just punters with a tent, and spent 24 hours being a motor sport buff. It never occurred to me that it was something I might want to do. I went back there for the first time a couple of years ago, to drive an E-type in the Classic. I walked a full lap on the Friday, then did a lap and a half in the E-type before the poor old thing threw a con-rod, but that brief experience made me realise what a mistake I’d made by never chasing that race.”

There would be podium finishes with the new Vectra in 1996, but the heights of the previous campaign would never be repeated. Indeed, Cleland would add just one more BTCC victory to his CV, at Donington Park in 1998, when he came through the field to beat occasional Ford Mondeo driver Nigel Mansell in a wet-dry race. “If I could revisit one event,” he says, “that would probably be it. For as long as my arse points south, Nigel wasn’t winning that race. We couldn’t have an F1 and Indycar champion coming in to kick our backsides, that was never happening. I did pass him cleanly, but if it got to the point that I’d had to use force… He was never going to win that race, trust me.”

Triple Eight had assumed responsibility for running the works Vectras in 1997, and the ’99 season would be Cleland’s last. “My contract was with Vauxhall, rather than Triple Eight,” he says, “I think Roland [Dane, team principal] wanted younger drivers. When Yvan Muller joined in ’99, it was really the start of his journey to becoming a multiple touring car world champion. Yvan had astonishing car control, but we spent plenty of time alongside each other on the grid, sometimes him ahead, sometimes me, but it became apparent that Roland saw Yvan as the future, which I understood. I could still hack it, but there were other things going on in my life at that time.

“I’d been in the BTCC for many seasons, and at the same time my father wasn’t very well [Bill died in 2000]; he had always looked after the business when I’d been away racing, but now I had increasing responsibilities, so it seemed a sensible time to stop.”

Cleland made just two starts in single-seaters, here in a Pilbeam at Doune in 1994

He would dabble with the British GT series in 2000 – “ I could probably have done a bit more of that, if I’d put my mind to it properly” – and carried on making his annual pilgrimage to Bathurst, finishing a career- best second in 2001 (see sidebar), but his time in the BTCC spotlight was over. Since 2013, he’s been back at the wheel of his 1997 Vectra in historic events. “I didn’t really want to buy it back,” he says. “I hated the f***ing thing when it was new. I did look at acquiring my ’95 Cavalier, but the owner wanted £100,000, and I didn’t think it was worth that! My son Jamie found the Vectra on Facebook and liaised with the owner, without telling me initially, but we ended up going to look at it. I recognised it as soon as I saw it, a car I’d first driven at Knockhill in 1997. Derek Warwick and Peter Brock shared it at Bathurst that year, and Brocky put it on its roof during practice. The marks from that are still visible, even today, so it’s very original. We’ve had it for about five years, and I’ve won more trophies with it than I did when Triple Eight was running it!”

Cleland didn’t like the ’97 Vectra in period but, after reuniting with it through Facebook, historic success soon followed

He plans to continue racing when possible, and is looking at restoring an Opel Monza, which has sat in his garage since it broke while he was sharing it with Jeremy Rossiter in the ’81 Tourist Trophy at Silverstone.

“I still love driving,” he says, “and look back very fondly at my time in touring cars. I’m not sure whether the camaraderie is quite the same now as it was for me, but we used to go out for some fantastic dinners, drivers and media folk all together. Alan Gow would join us – and he used to smoke at that stage, so would often leave the room.

“On one occasion, he’d left his jacket over a chair, so I pinched a credit card from his wallet. I subsequently volunteered to pay for dinner, obviously. Alan tried to stop me, but I insisted. It was in the days before you needed a pin number, so I just signed it as Alan Gow – I think it was for £800. We then went to play snooker, and Paul Radisich got the job of putting the card back.

“About two weeks later Gow called me, and when I picked up he swore at me for about 10 minutes without repeating himself. F*** was he angry. I promised we’d repay him, but he didn’t want that. He just told me I’d suffer at Snetterton, the next race, and I think I was summoned to the weighbridge about 18 times over the weekend. Every time I was pulled in, he’d be standing in front of the weighbridge with a big smile on his face.”

CV: John Cleland

Cleland spent his entire BTCC career with Vauxhall, despite rival offers

Jakob Ebrey

Born: 15/7/52, Wishaw, Scotland

- 1971-74 Cleland begins in autocross, rallycross, sprints and rallycross

- 1976 Scottish Rally Championship in a Mitsubishi Colt Lancer

- 1978 Drives in the Scottish Hillclimb Championship, racing an Opel Kadett GT/E

- 1979-85 Begins to make his mark in saloon racing with a variety of Opels/Vauxhalls

- 1986-88 Thundersaloons, Vauxhall Senator/Carlton; becomes champion twice with Vince Woodman

- 1989 Makes BTCC debut in Vauxhall Astra GTE and is crowned champion

- 1990-95 Drives Vauxhall Cavalier to 16 wins in the BTCC, and is champion in ’95

- 1993 Bathurst 1000 debut with Peter Brock in a Holde

- 1996-99 BTCC career begins to draw to a close, and makes selected British GT appearances in 2000

- 2001 Second at Bathurst 1000 with Brad Jones

- 2005 Final Bathurst 1000, is seventh with Dale Brede

- 2006-present Historic racing in various cars (including his 1997 Vauxhall Vectra, since 2013)