Ivinghoe: Britain’s lost racing circuit

A few years before Cadwell Park was opened in 1938 as Britain’s answer to the Nürburgring, a far more ambitious plan was hatched to create an undulating circuit near Ivinghoe in Buckinghamshire. Despite much promise, it proved controversial. Ian Wagstaff tells the story

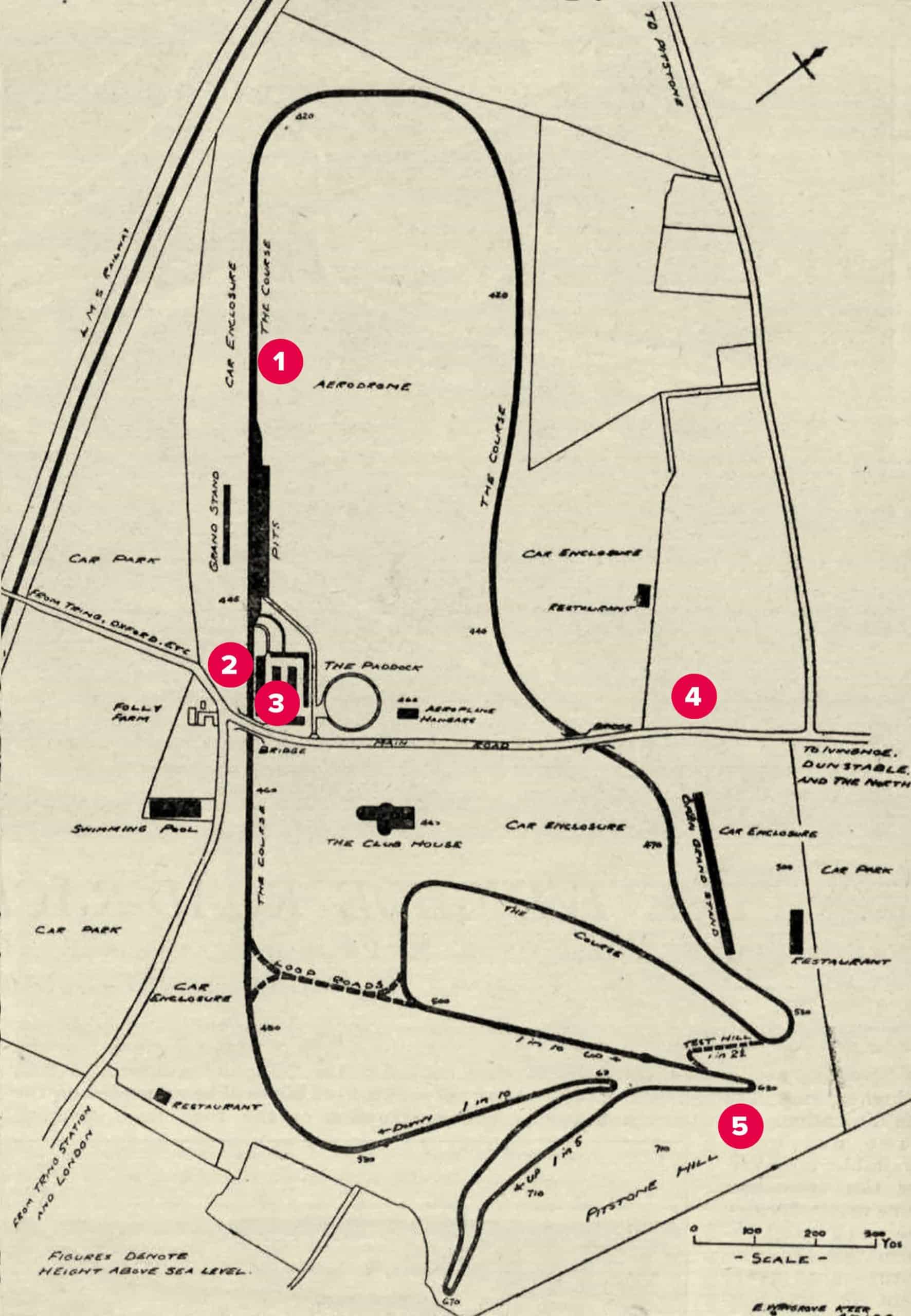

The proposed track layout from the early 1930s

Micky Burn did not realise the controversy and mayhem his words would cause. While his were the words, they were the thoughts of Sir Henry ‘Tim’ Birkin, for Burn was the ghostwriter of Full Throttle, the double Le Mans winner’s autobiography. Birkin thoroughly disliked Brooklands and said so in no uncertain terms. “[It is] without exception the most out-of-date, inadequate and dangerous track in the world.” Burn would later claim that he knew nothing about cars, so may have been unprepared by the furore that this caused at Weybridge.

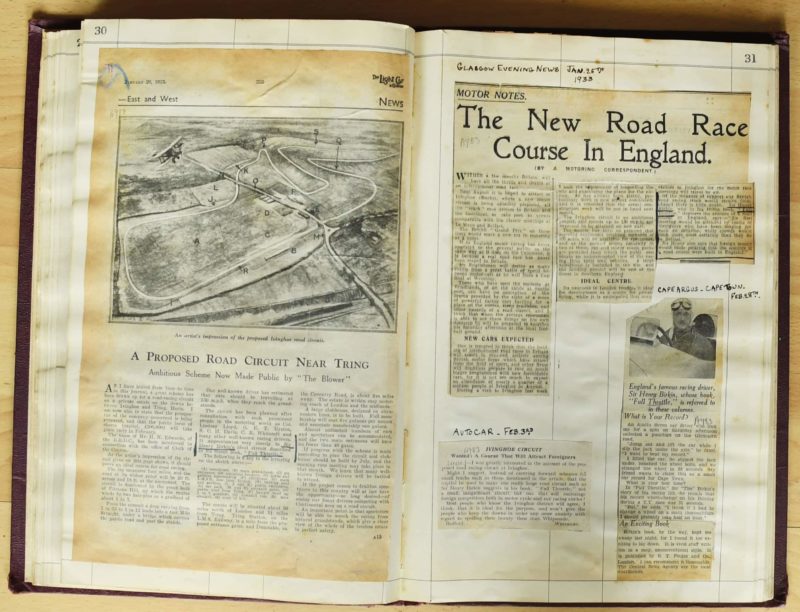

What Birkin wanted was a road circuit such as could be found on the continent. The Light Car magazine, in reporting a new venture early in 1933, thought it had found the solution. In describing “a proposed road circuit near Tring” it said, “it approximates very closely to the baronet’s ideal circuit described in his recent book”. Burn underlined the quote, cut out the page and stuck it into a thick cuttings tome that he was making of the book’s reviews. This also showed that the Glasgow Evening News connected the news of the proposed circuit to Birkin’s wish and visualised a “British Grand Prix”, while The Autocar reader ‘Whiskers’ made the link. “May I suggest, instead of carrying forward schemes for small tracks… that the capital be used to make one really large road circuit such as Sir Henry Birkin suggests in his book.”

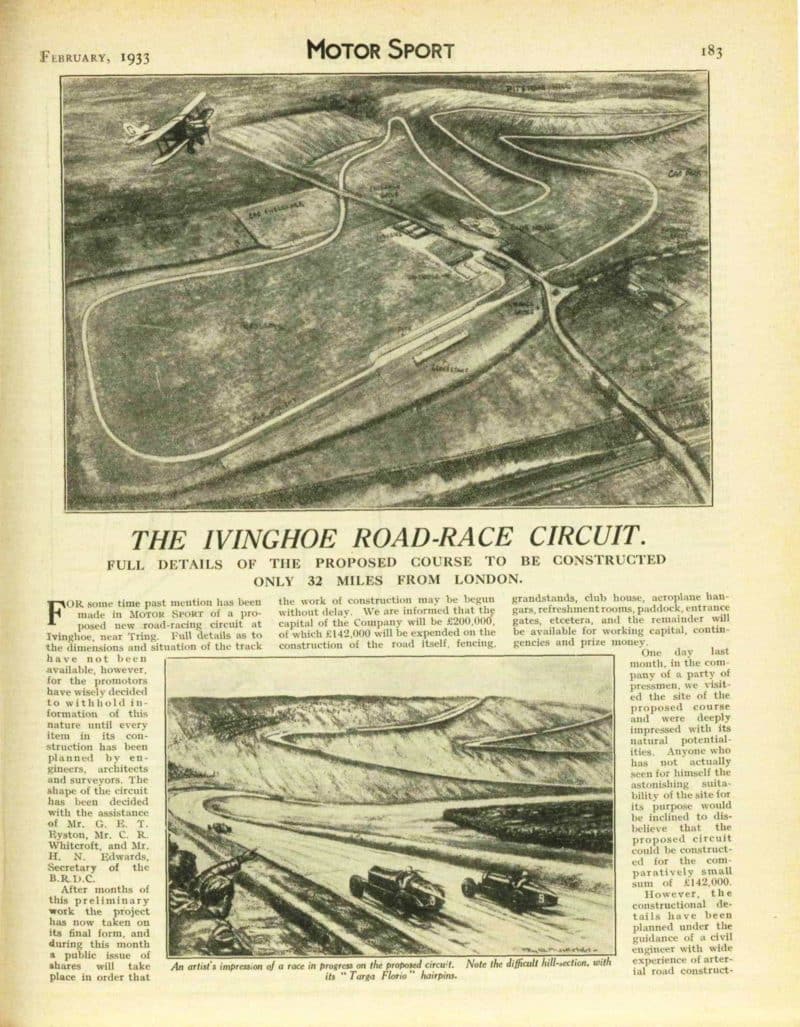

The natural topography of the site could have made for an excellent racing circuit.

Unfortunately for Whiskers and for British motor racing there were those who disagreed, in particular HE Howard, the chairman of The Hampden Association for the Preservation of Rural Buckinghamshire.

Rumours of a circuit just north of Tring began to emerge in the early 1930s. Writing as ‘The Blower’ in The Light Car, September 1932, Rodney Walkerley said he had been shown over a site “among the Dunstable Downs”. He reckoned that he could not divulge exactly where it was but did refer to it being near Tring and to a beautiful hill with the course snaking to its top before a descent to the grandstands with cars achieving 150mph. If any of his readers wanted to know more, he could put them in touch with those behind the project.

A month later, in Motor Sport, the anonymous ‘Boanerges’ said that he and Cecil Kimber had been “looking over the extraordinarily interesting site of the proposed road circuit in Hertfordshire, and finished up at a very comfortable hostelry at Ivinghoe”. There the pair had indulged in a race of ‘jumping beans’ before the MG founder showed off his popular ‘penny-and-the-glass trick’.

1. The main 130-150mph straight would have stretched out in the distance from here before curving around an aerodrome

Ian Wagstaff

2. The entrance to the track next to Folly Farm. The track would have run parallel to the road to the right of the photo with the grandstand to the far right of what is now a roundabout

Ian Wagstaff

3. This is where a bridge would have been built to take the B488 over the main straight

Ian Wagstaff

4. The only structural evidence that a motor racing circuit was planned for the area – what was once The Silver Birch café

Ian Wagstaff

5. The view from Pitstone Hill with the remains of a cement works in sight rather than a motor racing circuit

Ian Wagstaff

In November, Walkerley said that he knew more about this “excellent” scheme, even when it would have its first race meeting, but was not permitted to say anything. However, he was going to have “Lunch With a Man” and hoped soon to be able to tell more. Full plans were exposed to the press during a visit to the site on January 31 by a party of “impressed” journalists. A number of racing drivers also visited it and gave it their seal of approval.

Motor Sport said that the plans had been held back by the promoters until “every item in its construction has been planned by engineers, architects and surveyors”. The shape of the circuit had been agreed with the help of future Land Speed Record holder George Eyston, the secretary of the BRDC, HN Edwards, who was expected to be the clerk of the course, and CR Whitcroft. A public issue of shares was going to take place in the February. Construction was then expected to begin. The capital was to be £200,000 of which £142,000 would be expended on the construction of the (concrete) road, fencing, grandstands (for 10,000 spectators), a purpose-built club house (with an annual membership fee of five guineas), aeroplane hangars, refreshment rooms as well as paddock and entrance gates. The remainder would be available for working capital, contingencies and prize money.

“What the pressmen saw was an ideal 435-acre site for a track”

What the pressmen saw was an ideal 435-acre site. The hard chalk subsoil of the Chilterns meant a minimum of foundation would be needed for buildings and roads while there were no trees to be removed. Tring station, on the LMS railway, was a mile away leading to a vision of spectators streaming in from London.

Five alternative circuits were planned, the main being four miles long. Corners would range from fast sweeping curves to tight hairpins with a maximum uphill gradient of 1-in-5 and a downhill section of 1-in-10, “the great bulk” of Pitstone Hill being included in the site.

From the summit the road would drop down to a mile-long straight, under a bridge that carried the public road and past the grandstand before curving back in an easterly direction towards the hill. The width of the road would vary from 60ft opposite the stand to provide space for pit work to 18ft on the hill section.

Sir Henry Birkin’s derogatory words about Brooklands sparked a search for a new circuit

Excellent visibility was promised. Spectators would also have easy access to the circuit with 3000 cars able to pass through the 40 entrance gates every hour with 75 acres of outside car parks also being provided by the site.

It was expected that the track would create much-needed work opportunities not only for local inhabitants (unemployment was high) but for the British motor industry as well as the construction sector, the latter expected to provide 700 workers.

“Motor Sport was upset by the lack of genuine assistance from leading racing personalities”

Such was the confidence of the circuit’s backers that everything would be in place by July that a fixture was placed in the international calendar for August 19 with many foreign drivers likely to be invited. A national opening meeting was also planned for the month before.

There was much enthusiasm for the future of road racing in Britain. The estate roads of Donington Park had first been used for motor cycles two years previously and now a permanent track had been built. A proposal had been made for a circuit in the grounds of Gopsall Park, Leicestershire with an international date there fixed for September 30. Permission had also been secured from Brighton Council for a lease to be taken on downland near Portslade. Additionally, there was a scheme for a track at Burton-on-Trent with almost the whole of Drakelowe Park purchased “for a motor racing centre”.

An artist’s impression of how grand prix racing could have looked at Ivinghoe

By April, there was concern that the Brighton proposal was suffering from the objections of the locals, while there was no more news concerning Gopsall Park. Motor Sport was upset about the lack of genuine assistance forthcoming from leading racing personalities despite what they had to say at club dinners. However, it reported that Ivinghoe “is still likely to become a reality”. The Buckinghamshire branch of the Council for the Preservation of Rural England did not see it that way.

However, the land had been purchased and a café, known as The Silver Birch, was actually constructed north of the circuit on the B488, specifically to cater for the expected crowds. Despite what would or would not happen, it opened for business and would serve customers for many years despite its isolated nature. “I have long wondered why it was there,” says Jude Glenister, a present inhabitant of Folly Farm, next to where the entrance would have been, and now a bed and breakfast. The Silver Birch has latterly become a private residence but it still remains as the sole structural evidence that an Ivinghoe circuit was ever planned. A killjoy opposition was about to have its way.

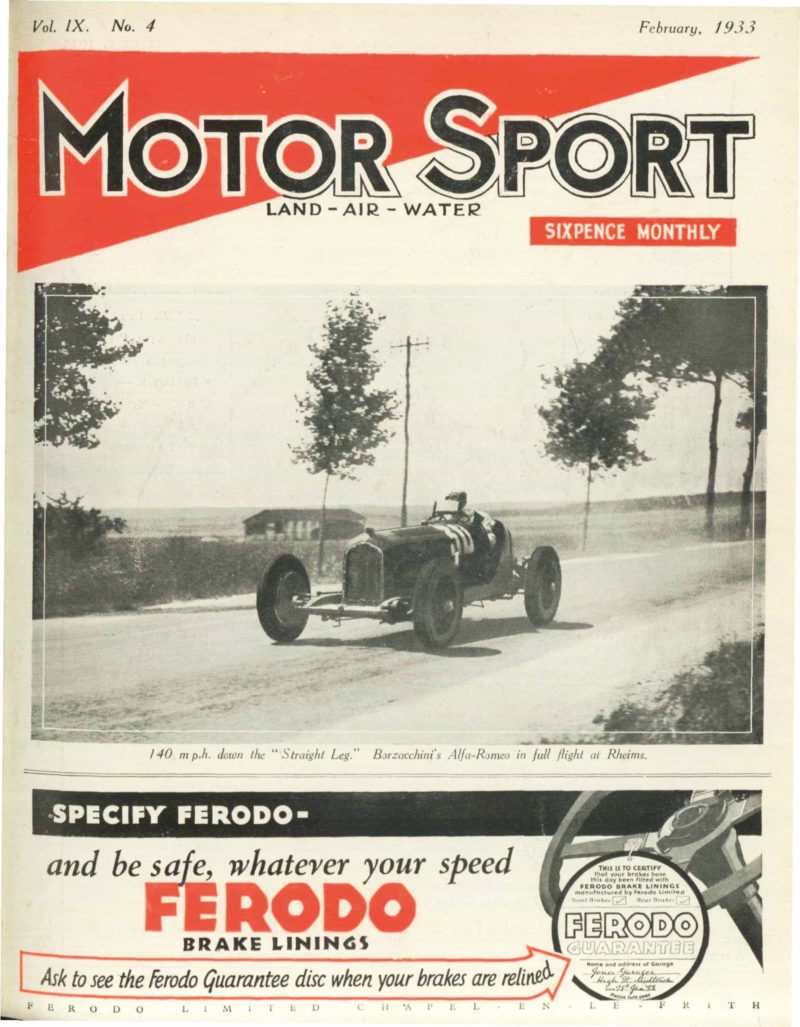

Motor Sport’s February 1933 magazine

Motor Sport’s reporting from February 1933.

The Autocar published a letter from the aforementioned Mr Howard. Motor Sport quoted from it but declined to include it in full. “Hoity-toity,” wrote Walkerley in The Light Car having been handed the letter by an editor with a “very grave” countenance. ‘The Blower’ had been one of the journalists who had visited the site back in January, returning to wax lyrical about the “fumes of racing oil [being] as perfume and the howl of a blown engine sweeter than the sound of Philomel, the nightingale”.

Said Mr Howard, “The Hampden Association has about a dozen arguments against the proposal to construct a motor race track near Ivinghoe, and will gladly put them all before any of your readers who apply for them.”

He complained that few jobs would be created and the countryside spoilt. Birkin responded: “It is silly to assume that a road course must spoil the view.” Walkerley went as far as to say that this particular area of downland was “very dull”.

It was not just the motor sport fraternity that could see the benefits. Writing to The Autocar, MK Hughes quoted the local Wing Rural Council: “We are fully alive to the necessity for preserving the beauty of the district. Nevertheless, there must be strong reasons for hindering development or interfering with the possibility of work being found for the unemployed.”

George Eyston had input on the track layout.

Getty images

Newspaper clippings on Ivinghoe from 1933

Another correspondent, DJC Gamble, referred to Howard’s “extraordinary statements”. Howard hit back at Gamble, who responded in kind. “Mr Howard, it seems, has thoroughly misunderstood me,” he wrote. Gamble’s cousin then joined in. As far as he was concerned, Howard’s stance simply reflected “the policy of too many people to-day, that of standing still and making no progress”.

By now, readers were out for Howard’s blood. “I am of the opinion that… Howard’s letter merely shows that he is trying to make much of a feeble argument,” wrote one. “It is apparently impossible to convince him that the circuit is not going to be a hideous blot on the landscape,” said another. Lewis Dunbar pointed out that he was a member of Rural Preservation Society and probably knew the area as well as Howard but felt that “we can quite well spare the site for the proposed course without in any way detracting from the beauties of the district”.

And so the letters came in. One reckoned that the proposed track would help the development of the road car. Another wrote that he was not suggesting Howard was “unpatriotic, but could he not consider the prosperity of his country rather than a few acres of rural Buckinghamshire?”

Pitstone Windmill has stood since 1627, and could have overlooked a race track, rather than a cement works.

Ian Wagstaff

There was a chance that Howard was losing his argument. The track was favourably discussed at a meeting of the Buckinghamshire County Council where one councillor stated “he had not met one resident who was in opposition to the scheme”. Walkerley understood that the council was “whole-hearted in their support of the scheme, and the promoters are doing all they can to make the circuit a centre of attraction rather than an object of repulsion”. The Motor reported that, while there had been no news issued recently, excellent progress was said to have been made and tenders for the work issued.

“The idea of having a sort of Nürburgring put in Buckinghamshire seems too good to be true”

Further down the line, the same magazine admitted that “a lot of people” were wondering what was happening but assured its readers that, despite what others had said about a lot of local opposition, a public prospectus was likely to be issued in the September. However, correspondence petered away. It seems likely that insufficient investors could be found and it became necessary to find another purchaser of the land, a cement manufacturer.

In 1937, Tunnel Cement began production on a 500-acre site. It can hardly have been what Howard had been looking for, and it was demolished in 1999. Today, Pitstone Hill is a nature reserve.

You can still drive up the B488 from Tring, stop at the roundabout by Folly Farm, enter the field at the far side of the road and find yourself in what would have been the proposed Ivinghoe circuit paddock. Better still, you can stand on the top of Pitstone Hill and dream of Bernd Rosemeyer racing around its slopes.

Bernd Rosemeyer in full flow at Donington Park in 1937. But should the big-hitters of the era have been racing elsewhere?

Getty Images

“The idea of having a sort of Nürburgring put down in the middle of Buckinghamshire seems too good to be true,” wrote Walkerley. Turned out, it was.

Today, the town of Tring is probably best known, if at all, by motor sport enthusiasts as the one-time site of a pig farm owned by a Harley Street dentist. There can be little doubt that the pig breeder’s son, Sir Stirling Moss, would have approved of having a circuit on his doorstep.