Richard Lloyd Racing’s giant-killing Porsche 956

It started in the pub with Richard Lloyd stating an interest in racing a customer Porsche 956. With the assistance of the original RLR team, Adam Towler tells the odds-defying tale of the modified ‘106B2’

Lee Brimble

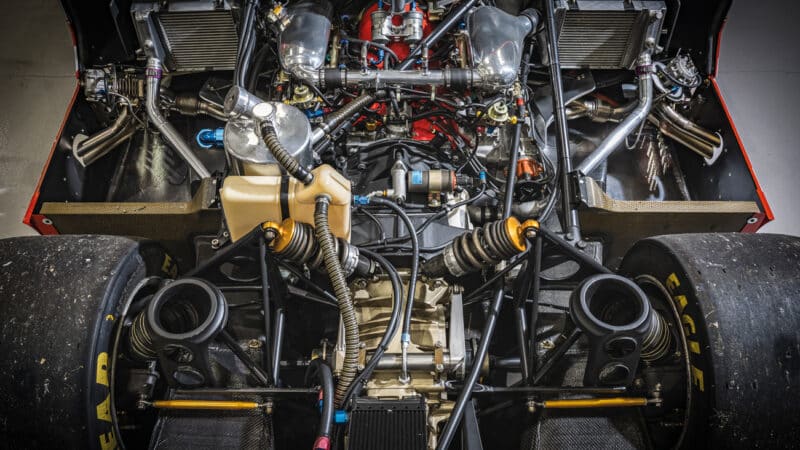

There’s a cheery “Good morning” from over our shoulders and Ian Sanders, the original chief mechanic of the Richard Lloyd Racing Group C team – or GTi Engineering as it was known in 1983 – walks into the Dawn Treader workshop. A smile breaks out across his face as he paces slowly around Porsche 956 chassis number 106B2, his inquisitive eyes flicking from one detail to the next, mechanic’s fingers caressing the instantly recognisable contours of arguably the greatest sports racing car ever built. It’s been more than 35 years since Ian last saw this car in the Silverstone workshops of Richard Lloyd Racing.

The emotive scene is broken by a dose of reality from another former mechanic that’s just wandered in. Wayne Greedy joined Ian at RLR for 1986: “There’s no orange peel, no [paint] flaking off, the white is white,” he shouts. “I remember scraping 14 layers of paint off the engine cover when we used it as a mould [for the 962 engine cover in 1987] – that’s how many times it had been repaired and painted…” Nothing could say more about the reality of a little team battling the factory squads in the world championship, and if there’s one thing you can say about Lloyd’s Group C exploits, it’s that they did exactly that.

Lloyd knew that to beat the factory, he’d need to adapt his 956

McKLEIN

Soon, the rest of our ensemble arrive: renowned designers Peter Stevens and Nigel Stroud, the former a long-standing collaborator of Richard Lloyd and the team’s aerodynamicist in the ’80s, the latter the man behind the unique tub and suspension of the Lloyd Porsches. And Grahame White, Richard’s friend and de facto team principal, in later years CEO of the Historic Sports Car Club. There could have been even more famous names with illustrious CVs, of course, and some who are no longer with us. So just what was it about Richard Lloyd that brought so many extraordinary people together?

Group C racing was quite a step for Richard Lloyd’s GTi Engineering team in 1983. Formed in 1977, when Lloyd started racing a Mark 1 Golf GTi in the British Saloon Car Championship, he campaigned VWs for three seasons with a best of second overall in 1978. In 1980 he’d graduated to Audi 80s, famously with Stirling Moss and a young Martin Brundle behind the wheel, and by 1981 was racing a Porsche 924 GTR in major sports car events. In portents of things to come, the team scored class wins (Brands Hatch in 1981; the Nürburgring in ’82), and had begun to modify its 924 for more speed, intriguing/bemusing the Porsche Motorsport department in the process. Then, from its small premises at Silverstone, it set out for Weissach in early 1983 to collect one of the first batch of customer-spec 956s, the type having already won Le Mans and the inaugural world championship the year before.

Keke Rosberg was keen to drive for Richard Lloyd Racing in the 1983 Nürburgring 1000Kms – run on the Nordschleife

“We were in a pub when Richard said he was going to buy a 956”

“Richard was a family friend anyway,” recalls White fondly. “I’d known him for a long, long time, and raced against him. We were in the pub when he said he was going to buy a 956 to go Group C racing, and I thought, ‘That’s quite brave.’ He said, ‘Do you want to give me a hand?’ It was as casual as that.”

“Back in England we found the brake pads were back to front”

When the RLR crew arrived to collect their awesome new toy they were bewildered to find little in the way of ceremony, the 956 parked in gloomy solitude. Stevens brought along some sticky plastic and hastily applied a livery for the photos that with finessing would go on to become one of the most recognisable of the decade: the red and white of Canon cameras. “We tried it around the Weissach track,” recalls Sanders, “and when we got it back to England we found the brake pads were back to front – metal to disc. They’d built it like it and ran it like it…”

More unpleasant surprises were in store for the team at the first race in Monza where upon arrival it became obvious that Porsche had delivered the car with the Le Mans-spec ‘long-tail’, not the short ‘sprint’ bodywork that the factory cars and German customer teams like Joest Racing were sporting. Was this Anglo-German needle? Maybe not, but it was an initial salvo in a love-hate relationship that would come to define the team’s progress.

From left: Wayne Greedy, Nigel Stroud, Grahame White, Ian Sanders and Peter Stevens back with ‘106B2’ at Dawn Treader Performance’s base

McKLEIN

Monza was a difficult baptism for the team, although a sixth-place finish was at least some reward. Tiff Needell, later to become a full time RLR driver in 1988/89, was brought in at the last minute to partner F1 refugee Jan Lammers. “I made my debut by coming out of the pits and getting to the Curva Grande, only to see my front wheel depart… They were coming off left, right and centre at the time, although the factory cars’ wheels never came off. I drove back to the pits on three wheels.”

The highlight of that first season was two third places, at Silverstone and the Nürburgring, the latter a particularly proud endorsement for a young team, given that incumbent F1 champion Keke Rosberg joined them. The Finn wanted to race on the Nordschleife before it closed to top-level sports cars for good, and there was no room at the inn with the factory, so Lloyd got the nod. Rosberg immediately charmed the team with his no-nonsense attitude.

Lloyd’s Porsche 956 106B2 looks pristine in the famous Canon colours thanks to Patrick Morgan

Lee Brimble

“He loved the Nürburgring,” recalls White, “and he loved that he could do that race. As for the weekend, well, talk about laid-back…he was absolutely charming. He didn’t want anything changed on the car; he didn’t test the car. After qualifying he came in and said: ‘That car will never go round that circuit any quicker than it’s just gone round there.’ He’d wrung its neck. And then he strolled off.

Team-mate Lammers was less enamoured with the situation: “It was like Russian roulette with two bullets – thank god I survived that. And it was a workout – each stint was six/seven laps. It was insane compared to today. With downforce, you change from driving with feeling to driving with commitment, because you know it will stick. At the ’Ring it went one level up from that: the whole lap you had lots of corners where you were committed.”

RLR knew its Porsche engines couldn’t give it the edge over the factory and competing customers. Stroud came up with the idea of an alternative chassis

The team’s results sheet for 1983 included a couple of thirds overall, but in 1984 it really hit its stride, winning at Brands Hatch and coming second at Imola. By now, the driving squad had settled around hot shoes Jonathan Palmer and Lammers. From admitting he was “the spoilt F1 reject” in ’83, the Dutchman grew to love his time with the RLR crew: “Many times I stayed in London or at Richard’s with his lovely kids. I spent many days watching Only Fools and Horses and Fawlty Towers. I’m very grateful.”

Lloyd wanted, and knew, he needed more. Firstly, the works cars were constantly evolving – they would always, inevitably, be one step ahead. Secondly, while co-operation between the factory and the top German-based privateers wasn’t exactly blatant, it was widely understood the relationship was strong. “It was a bit like a closed club – we always wondered what spec the engines were,” recounts White. “Porsche were helpful but no more,” adds Greedy. “That’s how it was. We always got the upgrades last.”

Stroud’s new 106B chassis was competitive – and may have saved the life of Jonathan Palmer

McKLEIN

Lloyd’s engines came from the factory on a pallet and went back there the same way. In effect, he was at the mercy of what Porsche felt he should have: the only way to get an advantage was to improve the car.

“It didn’t brake very well, not enough front end, it wasn’t stiff enough…”

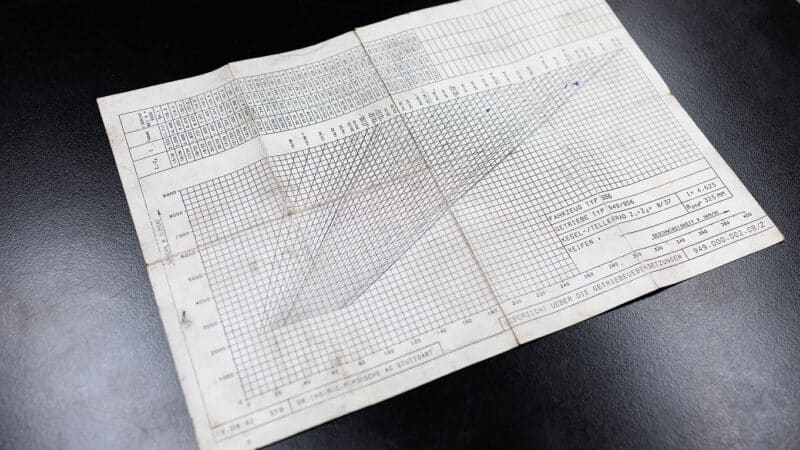

Enter Nigel Stroud, formerly of Lotus, ATS and others, then working as a consultant. “Richard wanted to beat the works car with something different,” says Stroud today, clutching a sheaf of his original technical drawings. “JP [Palmer] had been on to him about how bad the car was – it didn’t brake very well, not enough front end, it wasn’t stiff enough… typical driver moans and groans. We measured up the best we could and came up with a design for a chassis, and I’d previously used honeycomb on single-seaters and felt it was the right way. We weren’t into carbon then, otherwise we would have done it. It wasn’t seriously considered or in budget.” The result was a new honeycomb alloy tub that was stiffer than the works cars – particularly important in what was a ground-effect car – and also safer too.

Original technical drawings

McKLEIN

“I felt at the front, the suspension needed to have a system to adjust the rising rate, as it was a ground-effect car, so that’s why we went to pull-rod, but we tried to keep as much [of the Porsche] as possible; for the front brakes we had twin calipers, rather than single, with different uprights.”

After its Brands victory Lloyd sold 106 to the Brun team and christened his new car ‘106B’, while Stevens had been busy too, developing a split rear wing and nose wing as well, along with a revised underbody. It was immediately quick, claiming second place at the Imola 1000Kms, and the team entered 1985 on a high. It would be a year of drama.

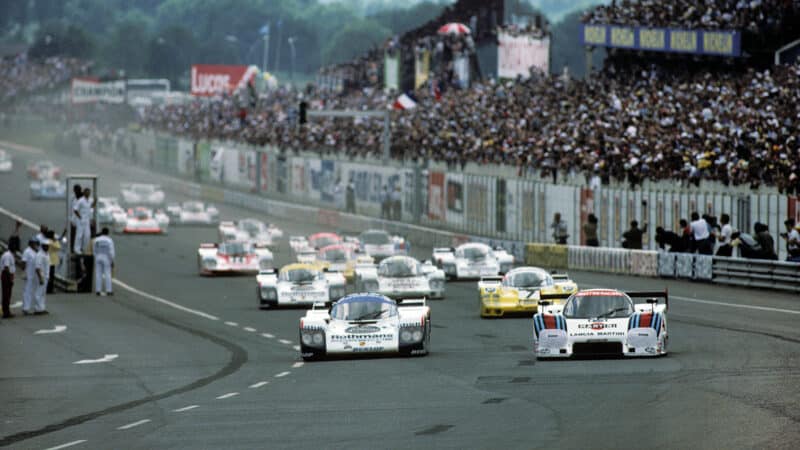

The stats say that the team, now known as Richard Lloyd Racing, scored three fifth-place finishes and a brilliant second overall at Le Mans. Yet it was also a season where the vulnerability of a 956 driver was cruelly exposed, firstly at the poorly supported Mosport round when Kremer’s Manfred Winkelhock succumbed to head injuries after hitting the wall at Turn 2. Then at Spa Palmer had a suspected failure of the right front tyre going into the Pouhon corner, and hit the wall. The tub crumpled, to such an extent that the gearlever hit Palmer in the eye, and it took some time to remove him from the crumpled remains of the Porsche. Even worse, in the race Brun’s Stefan Bellof was killed attempting to pass the works 962C of Jacky Ickx at Eau Rouge.

Then as now for stunning 106B2

“I wouldn’t say I was scared but I had a bad feeling about Le Mans”

For Lammers it was too much: “There is every evidence to say Jonathan might not have survived in a standard chassis. He was extremely lucky. It did worry me. I wouldn’t say I was scared, but I just listened to my intuition. I had a bad feeling about going to Le Mans and I tried to listen to that inner voice.” The Dutch driver didn’t travel to France and finished the year with TWR Jaguar.

The sports car world reeled on its axis, and for Lloyd there was nothing to do but rebuild. That meant a new car, now colloquially known as ‘106B2’.

Formidable Group C opposition at Le Mans 1985

McKLEIN

For 1986 B2 had a new livery, the colours of Liqui Moly rebranding the team, and a new driver pairing in Mauro Baldi and Bob Wollek, both of whom the RLR mechanics rated to the highest degree. Another victory at the Brands Hatch round was the season’s highpoint.

As Stevens notes, the Lloyd way of going motor racing wasn’t all hard work and no play: “The team was probably more keen to win then anybody, but that didn’t preclude it being fun. One of the things Richard didn’t believe in was dashing home after the race.”

“It was a big family atmosphere, and when someone made a mistake there was no kicking off,” says Wayne, “We had a lot of respect from the Porsche team themselves. We’d go out with some of the mechanics for a few drinks – sometimes that got out of hand! We had a close relationship – an admiration.”

Poster boy: Peter Stevens was the man behind the Canon and – following guidelines – the Liqui Moly liveries of the 106B2

Lee Brimble

“You do the race, but you’ve got to have a nice time,” adds White.

For 1987 the team would build a new 962C-based car, but that’s another story; the Porsche team from Britain had already well and truly made its mark.