Aintree: Britain’s forgotten F1 circuit

Before Red Rum was thrilling the masses in the Grand National, Liverpool’s world-famous racecourse hosted the British Grand Prix with Formula 1 racing cars. For Mike Doodson it holds fond memories

“A great start by Moss rocketed him into second place”

Grand Prix Photos

Just how good was Aintree, the circuit situated six miles north of Liverpool’s city centre? Created on the hallowed precincts of the Grand National horse race, it opened to international-class motor racing in 1954, with plenty to recommend itself. It offered good public access (railway station a short walk away) and convenient facilities. This included restaurants and covered grandstands – benefits of the venue’s long-established equestrian heritage – which would bring in discriminating patrons.

Jack Brabham, winner of the 1964 Aintree 200

Grand Prix Photos

The early GPs there attracted substantial crowds, with the 1955 event reputed to have drawn a race-day attendance of 150,000. Curiously, it was not to last. Two factors which contributed to the collapse of the Merseyside idyll, following a non-championship F1 event in 1964, were safety concerns (lack of run-off areas) and the boom in car ownership, which worked in favour of more remote track rivals.

There were other negatives which counted against Aintree, not least among them the sickly aroma from the British Enka (artificial textile) factory on the nearby Ormskirk Road. Flat and grimily industrial, it lacked the scenic charm associated with continental circuits.

The Aintree Racecourse was opened in 1829 and had been hosting the Grand National steeplechase race since 1839. It would become one of the greatest horse races in the world. The management of the racecourse had been in the hands of several generations of the Topham family since the 1840s. In 1932 the property became the responsibility of 47-year-old Arthur Topham, who had no interest in carrying on the family tradition. By chance, his wife, a former vaudeville performer and actress, was happy to step in.

It was not lost on the former Hope Hillier, now the redoubtable Mirabel Topham, that one week of horse racing per year was bad business. Following a visit to Goodwood, she decided that Aintree deserved dual use, as a result of which the motor racing circuit was designed and built, for a sum of £100,000, over just three months. Two events were held in 1954, both won by Stirling Moss, the success of which led to an agreement with the international authority for the British GP to run on Lancastrian soil in 1955.

Moss in the one-off Cooper-BRM, Aintree 200, April 1959.

Although I missed that first GP, I was present at Aintree’s non-championship F1 event two months later – the first motor race I attended. I suspect that my father, a municipal accountant who rose to become the county treasurer of Lancashire, had been sent some complimentary tickets. It was his idea to drive us to Aintree from Preston in the family Hillman Minx. By the time we got home that night, his son had acquired a new passion.

Ferrari team-mates Wolfgang von Trips and Phil Hill flank Laura Ferrari after the 1961 British GP

Getty Images

I would later encounter a celebrated fellow Northerner whose love of motor racing extended as far back as mine. This was George Harrison of The Beatles. Fascinated by Tyrrell’s six-wheeler, this closet F1 fan had shown up at the first GP at Long Beach in 1976. He was introduced to the British sports correspondents flocking around him. It was in the paddock in Adelaide 10 years later that Mr H and I found ourselves chatting about our Northern roots and our introductions to the sport. I mentioned the 1955 race at Aintree, and rather pompously mentioned how my father had driven me there. “I drove there with my dad, too,” said George. “I was on the top deck and he was down below, collecting the fares.”

Jack Brabham, Cooper T51, 1959 British GP.

Getty Images

The British GP would return to Aintree in 1957, 1959, 1961 and finally in 1962. From then onwards, Silverstone alternated the event with Brands Hatch. Aintree was history. The non-championship F1 event in 1964, won by Jack Brabham in one of his own cars, brought down the curtain on international racing at the venue. By then, Mrs Topham’s enthusiasm was waning. Although she announced that the entire facility was for sale, no deal went through because there had been a provision in the contract which she had signed when acquiring the racecourse in 1949 that it would not be sold to be developed. It was finally sold in 1973 but it has never been developed.

Jim Clark, 1962

Grand Prix Photo

Aintree still holds strong memories for me. Of these, the stand-out race was the non-championship F1 200 in 1959, held a couple of weeks after I had left Rugby School. I was now the holder of a driving licence, so on the way down from Preston I shared the wheel with my father. As we pulled in to the car park, we spotted two very senior officers of the Lancashire force, dolled up in their number one meet-the-Queen uniforms. They greeted my old man almost deferentially, then asked me if I would like a close-up view of the action.

Two unusually affable sergeants ferried me out to the Melling Crossing and parked me behind a wooden stanchion, so close to the racing line that I could almost touch the cars. It was not until several years later that I realised why I had been singled out for such privileged treatment. It was my father’s signature, in his capacity as county treasurer of Lancashire, that appeared at the bottom of every salaried policeman’s monthly payslip.

Lotus driver Graham Hill, No28, among the midfield in the 1959 British GP.

Getty Images

I like to think that the 1959 race at Aintree, though not a ‘proper’ grand prix, would prove to be a milestone in the technical development of F1. The perennially optimistic BRM outfit had two of its stylish front-engined cars in the field, but had registered its interest in the swelling tide of rear-engined doctrine by lending one of its four-cylinder engines to Rob Walker’s independent team, Stirling Moss’s employer, to be fitted into the back of a Cooper chassis which had been bought for the purpose.

“A great start by Moss rocketed him into second place”

The 2.5-litre BRM powerplant, bulkier than the regular Coventry Climax units, was a tight fit in the little Cooper. An oversize radiator had been crammed into the nose and Moss’s seat had to be pushed uncomfortably forward. The Walker team’s mechanic Alf Francis had also made some alterations to the front suspension. After a brief test in Modena, where it had been fitted with the Valerio Colotti-designed gearbox commissioned by Mr Walker, it went to Aintree, where Moss was hoping to win the 200 for the fourth time.

“The car shuddered violently at the front under heavy braking and was really difficult to drive,” Moss told Doug Nye. So much for the Alf Francis ‘improvements’. Our hero managed no better than sixth fastest time in qualifying, a full 2sec slower than Masten Gregory in a Cooper-Climax. There were two factory Ferraris, front-engined V6 Dinos, with Jean Behra qualifying in second place and his new team-mate Tony Brooks back in eighth.

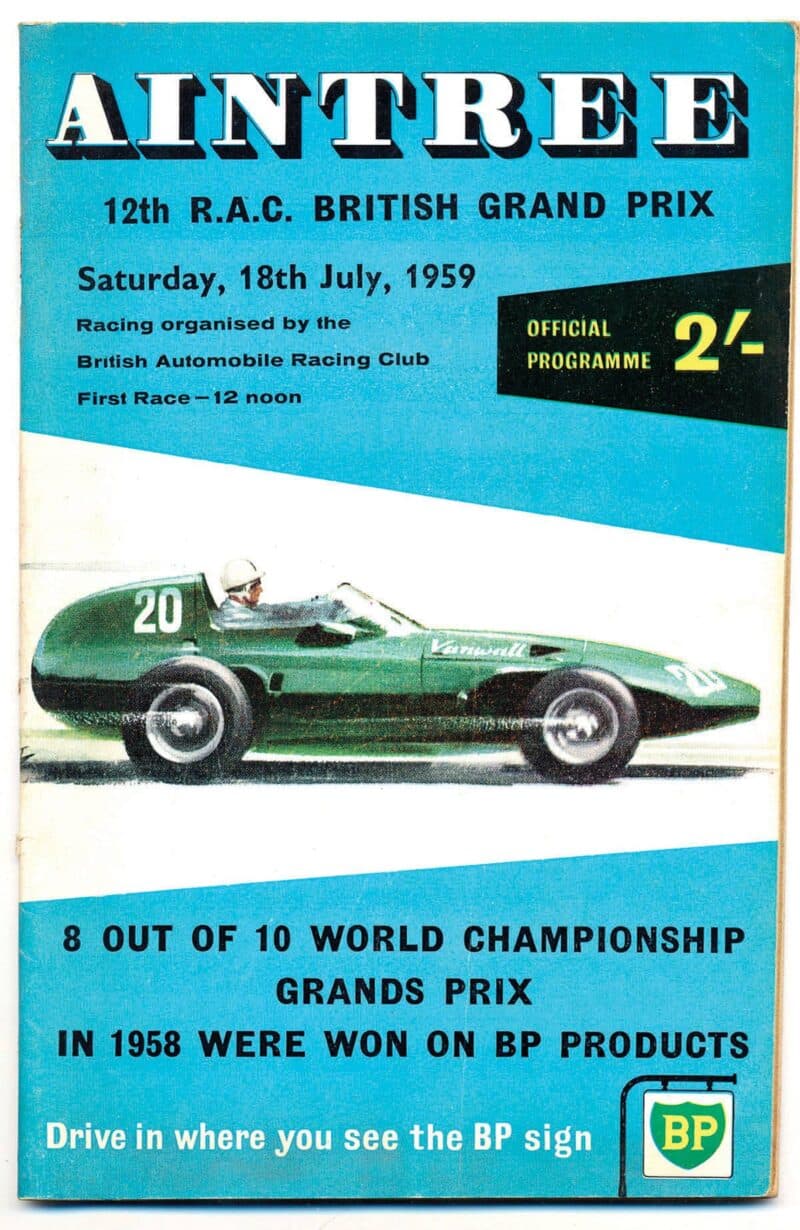

1959 programme

Getty Images

A great start by Moss rocketed him into second place behind Gregory, until the latter’s clutch failed, lifting Moss and the ill-behaved Cooper-BRM into the lead. Somehow he had then pulled out half a minute on Harry Schell’s BRM and Behra’s Ferrari. But neither of the British cars was destined to finish: Schell’s hard-pressed BRM expired on the circuit and Moss pulled up in the pits with the first of the several niggling failures in the Colotti box that would blot the rest of his season.

The real casualty of that 1959 season would be Ferrari. Although Behra and Brooks took a 1-2 result at Aintree, both the works Cooper-Climaxes and Walker’s mongrel had the legs on them. On the first lap, the red cars were running sixth and eighth: retirements had allowed them their success. Whether or not you believe Maranello’s official reason (“union disagreements”) for the Scuderia’s absence from the British GP at Aintree in July, it surely saved Enzo’s front-engined orthodoxy from ignominy on the Mersey.

Von Trips, 1961 British GP; his win here lifted him above Phil Hill in the drivers’ championship

Getty Images

If Aintree had kindled my yearning to become a racing driver, it would also be the scene of that ambition being crushed. In 1966 I had acquired an early model U2 Clubman. It was looked after by a pal who owned a Gulf service station in Manchester, who had painted it in the brand’s pale blue and orange colours. We trailered it to Aintree, where the local club ran training sessions on Tuesday evenings. I climbed aboard, did a few laps and decided to go for a quick one. Coming down the main straight, I screwed myself up to brake at the last imaginable moment. As I hit the pedal, I was overtaken by the entire Chevron factory team: Tim Schenken in an F3, Peter Gethin in an F2 and Chevron boss Derek Bennett in a GT, all three of them international race winners, indulging in a shake down.

It was then, I believe, that the Almighty kindly signalled to me that I was not cut out to drive racing cars. Instead, I switched to marshalling (I flagged two British GPs) and, later, to writing about the sport. I don’t regret not becoming world champion. But I do admit to missing Aintree, stinky breezes and all.