McLaren’s unstoppable force: Neil Oatley designed Senna's F1 title winners. Now he’s targeting Le Mans

For half a century, Neil Oatley has lived and breathed Formula 1 and is still involved on a day-to-day basis with McLaren. Retirement? No time soon…

Getty Images

Here is a bold claim with which to kick off an interview/profile: no one has ever devoted to motor sport so great a proportion of such a long working life as has Neil Oatley. He is a McLaren stalwart, having worked for the company for the past 39 years. He spent most of those as-near-as-dammit four decades as a key cog in its legendarily successful Formula 1 wheel, but now he focuses on the company’s F1 Heritage operation and its LMDh (Le Mans Daytona hybrid) World Endurance Championship Hypercar project. So he works a bit less hard these days than he used to, right?

“Er, no, wrong,” he sheepishly admits. “Much to my wife’s disgust, I work as many hours as ever.” I am astonished. After all, he is 71. Moreover, when I was McLaren’s comms/PR chief, from 2008 to 2017, Oatley was famous among all our colleagues for his relentless industry, working long stints into the evenings and even nights, regarding the Saturdays and Sundays of non-grand prix weekends as ideal opportunities to get stuck into thorny projects that were less easy to bend his remarkably fecund mind to during the cut and thrust of the working week.

Neil Oatley, left, Spa, 1974.

Gareth Rees

He will not say a lot about McLaren’s LMDh WEC Hypercar project – our interview is not his first media rodeo and he knows all about the importance of technical, strategic, and commercial confidentiality – but he will allow that it is “very exciting”. However, it is already well known that McLaren’s return to the top tier of sports car racing is scheduled for 2027. He will not make any predictions – why tempt fate? – but the company’s ultimate ambition is to win the Le Mans 24 Hours outright, which iconic achievement it first and last accomplished in 1995, courtesy of the fabled McLaren F1 GTR, JJ Lehto, Yannick Dalmas and Masanori Sekiya. That win was a surprising one – a rare occurrence of a fettled-for-the-track road-going supercar beating purpose-built prototypes – but the 2027 McLaren LMDh WEC Hypercar will be a bespoke creation produced by Dallara and run in collaboration with United Autosports, featuring a V6 twin-turbo engine. The project will be led by James Barclay, whom readers will know from his column in Motor Sport, who will join as team principal in September from his most recent role as team principal of Jaguar TCS Racing in the FIA Formula E World Championship,.

My interviewee will say more about McLaren’s F1 Heritage operation. “I really enjoy it. For example, we recently built a ‘new’ [McLaren] M23 almost from scratch. That was quite a tough job, a mixture of engineering and research, because back in the day [the 1970s] many things on F1 cars were made on a buck and jigs in the workshop and never actually drawn. So we didn’t have a detailed blueprint to rely on, which meant that instead we had to work with the few drawings we had plus archive photography.” The M23 is one of the greatest racing cars of all time, of course, having been driven to F1 world championships by Emerson Fittipaldi (1974) and James Hunt (1976), and the car that Oatley and the F1 Heritage team brought back to life was chassis 15, some but not all of which they had found languishing apparently unloved in the company’s treasure trove of racing artefacts.

Getting Pedro Rodriguez’s signature in the paddock at Brands Hatch, 1968

Gareth Rees

“You say you work as many hours as ever, but do you have any hobbies?” I ask him.

There is a pause this time. “Well,” he says, frowning, “I enjoy watching and reading about all kinds of motor sport, including series I don’t work on, like IndyCar, motorcycle racing, all that.”

“What about a hobby that has nothing to do with motor sport?”

He is momentarily stumped, then he rallies – literally. “Ah, well, my wife [Peta] and I have a classic Lancia Fulvia, which I’ve restored to HF spec, and we enjoy going on long rallies in it. We’ve done some in the UK, but also in France, Spain, Portugal and Germany. Peta enjoys them, and we share driving and navigation duties. I tend to do the special stages, but she does her fair share of driving in between. She’s not bad at all.”

Good try, Neil, old chap. I would not class rallying a Lancia as “a hobby that has nothing to do with motor sport”, which was the phrase I used in my question, but it sounds like a lot of fun. I push him again and he reveals a hinterland of other enthusiasms: “I enjoy reading and listening to music, both recorded and live, and our home is crammed with books and discs. I mostly read travel books, books about sport, and of course books about motor sport. In fact I have to admit that my ‘to read’ pile of motor sport titles is now well into four figures. My wife says she is waiting for them to push through the ceiling. I also love cricket, and I go to quite a few matches in the south of England. Oh and I do a bit of gentle mountain biking, too.” Nonetheless, if you are beginning to form the impression that Oatley is a man whose devotion to automotive sport is unusually tenacious, you would be right.

So where did it all begin? “I was born in Camberwell, in south-east London, and in the very early 1960s, when I was about six years old, my dad began to take me to watch speedway racing and stock car racing at the New Cross greyhound racing stadium [which was closed in 1969],” he explains. “My dad was a big speedway fan, but at that age I already preferred cars. Stirling Moss was my hero, just as he was the hero of all young English boys who loved motor sport in the 1950s and early 1960s. His racing career came to an end in 1962, with his accident at Goodwood, which was a big story at the time and a sadness for boys like me, although I think I was probably still a bit too young to be deeply upset by it. But I remember seeing all the newspaper reports, with all the photographs, many of them very graphic actually, showing quite a lot of blood. Something like that wouldn’t be reported that way nowadays, but it was a different time.

Williams’ sole driver in 1977 was Patrick Nève – here struggling to qualify for the French Grand Prix in the ‘March mash-up’

Grand Prix Photo

“In 1963 we moved from Camberwell to a village in north-west Kent. It was quite near Brands Hatch, which meant that, aged nine, I was able to cycle off to Brands on my own to watch lots of racing there: saloon car races, sports car races, motorcycle races, all sorts. It was great. And the Crystal Palace circuit was only a short train ride away, too – and, again, there I was able to watch many different categories of racing.

“I particularly remember the 1965 Race of Champions at Brands, which was the first F1 race I ever went to. Jim Clark crashed his Lotus 33, while leading, just 50yd away from me. He hit the bank behind the pits. I remember it like it was yesterday. Clark was one of the all-time greats, of course.

“And the following year, 1966, my dad went with me to Brands, for the British Grand Prix, and two days after that race, on the Monday, because the British Grand Prix was often on a Saturday back then, there was a filming day at Brands with many of the F1 drivers and cars for the movie Grand Prix. They needed volunteers to fill the grandstands, and I begged my mum and dad to let me skip school for the day so that I could be there. They refused – but, to add insult to injury, they decided to be there instead of me. I was 12 when Grand Prix came out. I’ve watched it dozens of times since then and I’ve never managed to spot my mum and dad in the crowd, but they were there. At the time I really wished I’d been there too, but I’ve got over it now.” He chuckles, then shrugs.

“Bruce was a driver, an engineer and a team owner rolled into one”

“Then in 1968 I saw Bruce McLaren win the Race of Champions at Brands. He was racing a McLaren M7A – a truly beautiful car – and I got his autograph that day. Those were my two biggest childhood heroes really –Stirling Moss and Bruce McLaren – and Graham Hill for a while, too. But when I saw Bruce racing those fantastic Group 7 cars at Brands, I was sold. Here was a driver, an engineer and a team owner rolled into one.

“I was OK at school, nothing special, better at sciences than arts, and, by the time I was taking my O levels and A levels, I was determined to work in motor sport. But when I mentioned my ambitions to the school’s careers officer, he pooh-poohed the idea. In fact he regarded it as a huge joke. But, undeterred, I tailored my schoolwork to try to achieve my goal. I won a place at Loughborough University to study automotive engineering, and there it was that I first met like-minded people: guys like me who were obsessed with motor sport. Most of them were into rallying rather than circuit racing, actually, but they were still very much my kind of people. One of them was Peter Morgan, who won the 1978 Esso Formula Ford 1600 Championship in a Lola T540. He went on to work for Reynard for many years. He was a great guy. He died two years ago, sadly.

“As I said, I was OK at school, nothing special, and I was much the same at university. I ended up with a 2:2. Getting a 2:2 would make it difficult to get into F1 as an engineer these days, because it’s so competitive, but it was a bit easier back then. Anyway, after Loughborough, I joined a small engineering company in Chesterfield, which was a great place to learn because they made all sorts of things to do with the testing of all sorts of vehicles, such as test rigs, rolling roads and so on. It was small, as I say, which meant that we all had to get involved in everything the company did. It was a fantastic way to acquire a ton of knowledge fast. Then, a year later, 1977, by which time I was 23, I spotted a classified job ad in the back pages of Autosport for a design engineer vacancy at the Williams Grand Prix Engineering factory at Station Road, Didcot. I applied for it and I got it.”

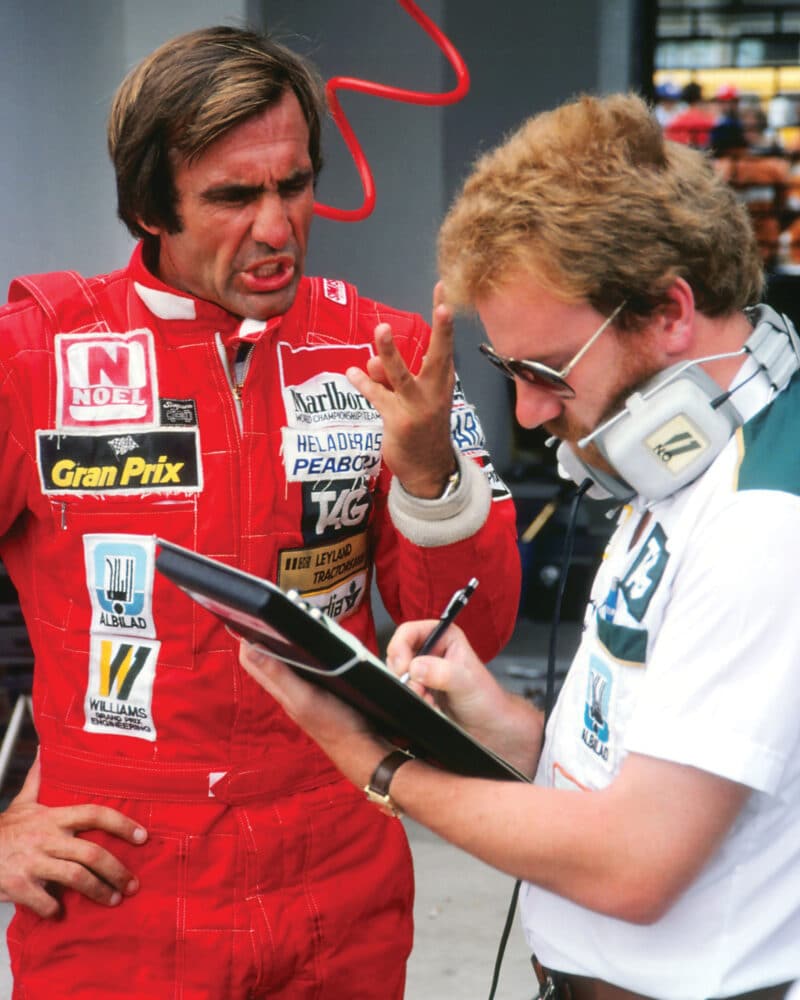

Williams driver Carlos Reutemann makes his point to Oatley at Rio in 1981; he’d win the GP.

Perhaps now is a good time to ask Oatley to tell me – and thereby you also, dear reader – the truth about the persistent rumour that the F1 car that Williams raced in its first year, 1977, driven by Patrick Nève, was not an ex-works 1976 March 761 as the record books show and as March boss Max Mosley described it when he sold it, but a bitsa made up of odds and ends from various mid-1970s March F1 cars including a 1975 751 and even a 1974 741. Oatley laughs, leans back in his chair, then says, “Well, we may never know. Frank [Williams] bought that car before my arrival, but, yes, the story goes that he’d been told that it was a 761, but when his guys stripped back the paint to re-livery it in the colours of the Belgian brewery Belle-Vue, which was the sponsor that Nève had brought with him, they found old paint schemes from previous Marches. So I’d have to say that, yes, the car was probably a mix of 741, 751 and 761 bits.” So now we know.

Nève was not a bad driver, but he was not a brilliant one either. In 1977 he and Williams entered 11 F1 grands prix in that March mash-up. They scored no points, and they failed to qualify three times: at Dijon, at Hockenheim and at Zandvoort. But Frank Williams and Patrick Head had big plans for 1978. “That was a fantastic time,” Oatley remembers. “I was Williams employee number 13. When I arrived, Patrick was the only other engineer. He didn’t mind that I’d only got a 2:2 at university – because so had he. He used to joke that guys who’d got 2:1s and firsts were too academic to be practical. Well, I don’t know about that, but Patrick was definitely practical. He was a brilliant, hard-working, no-nonsense engineer and a wonderful person to learn from. He was also very patient with me, which probably isn’t what he’s known for. The first proper Williams was the FW06, which he designed in 1977 for the 1978 F1 season. I helped out with the creation of that car. It was very efficient and very light, and it had a nice structure. It was probably the definitive Cosworth-engined garagiste design of the pre-ground-effect era. Oh and for 1978 we had a new driver: Alan Jones.

“Frank ’s unshakeable enthusiasm was incredibly infectious”

“Actually, Frank’s and Patrick’s original intention had been to hire Gunnar Nilsson for 1978, but then he decided to go to Arrows instead. But that came to nothing, because he developed cancer, very sadly, so he never raced at all after 1977, and he died in 1978. But, yes, Gunnar had been their first choice. However, when that idea came to nothing, they went for Alan instead – and, without wishing to criticise Gunnar in any way, because he was a talented driver and a lovely guy, and he’d won the Belgian Grand Prix for Lotus in 1977, I think Alan was probably stronger. Actually, ‘strong’ is absolutely the right word to use to describe Alan. He was not only strong physically but also strong-willed. He had a lot of guts, he was very determined, he had a great sense of humour, and he, Frank and Patrick quickly became firm friends. They were about the same age, of course. At the beginning of the 1978 F1 season, Frank was 35, and Patrick and Alan were both 31.

“The three of them formed an incredibly close, very productive and mutually beneficial relationship. And I was so lucky to be there with them, albeit that bit younger than them, and learning so much from them so fast. Undoubtedly, Patrick has been the biggest influence on my career, and Frank’s unshakeable enthusiasm was incredibly infectious. I remember that at my interview he just wanted to talk about racing rather than ask me about what I’d done in engineering. But that was Frank.”

Frank Williams at the team’s Didcot HQ, 1978

Williams did not win an F1 grand prix in 1978, but Jones finished second at Watkins Glen and he might have won at both Long Beach and Brands Hatch had the FW06 been more reliable. The following year, 1979, Head’s first ground-effect car, the FW07, was unveiled, and it was super-competitive from the get-go. The team was growing in size and stature, and a second driver had duly been drafted in for the first time: Clay Regazzoni. “Clay was older,” Oatley recalls. “He was 39 when he arrived at the beginning of 1979 – and he’d been a favourite of mine when I was a teenage fan. So I was excited to work with him. He wasn’t as quick as Alan in qualifying, but in the races he gradually warmed up and by the end of some of them he was often flying. We saw that at Monaco [where he finished second] and Monza [where he finished third], for example.

“At Silverstone Alan was on the pole by a mile, and Clay had qualified in P4. Alan should have won that race easily – he was in a commanding lead until his water pump failed at half-distance. So Clay took over, winning us our first grand prix. It would have been more fitting if Alan had won Williams’ first race, given all he’d done for us, but, although we were gutted for Alan, we were chuffed for Clay. Alan was bitterly disappointed and he left the circuit before the end of the race, but Clay was all smiles on the podium, swigging Lilt [rather than champagne, in deference to the team’s Saudi sponsors]. Having said that, I remember that at one point, when the sponsors weren’t looking, Frank allowed himself a glass of whisky and a cigar, which was unheard-of for him. He was a fitness fanatic in those days, and he hated drinking and smoking.”

Alan Jones, Williams’ world champion in 1980, was at Beatrice by 1985, teaming up once again with Oatley

Grand Prix Photo

Fate was kinder to Jones for the rest of the season, during which he and the Williams FW07 showed themselves to be the dominant force in Formula 1. Just two weeks after his disappointment at Silverstone, he won at Hockenheim, then he won again at Österreichring, Zandvoort and Montreal. The following year, in the updated B-spec version of the FW07, he won in Argentina, France, Britain, Canada and the United States, securing his only, and Williams’ first, Formula 1 world championships.

His team-mate that year, 1980, replacing Regazzoni, was Carlos Reutemann. “Ah Carlos,” Oatley says with a sigh. “He was brilliant, as quick on his day as anyone, but he had off-days as well as on-days. He didn’t have Alan’s strength of mind. Sometimes he could be absolutely fantastic. For example at Monza in 1981 he took the front wings off and he drove an incredible lap in qualifying, ending up P2, not quite as quick as René Arnoux’s superfast turbo-powered Renault on that out-and-out power circuit but a long way ahead of everyone else, and a whopping 1.2sec ahead of Alan. Then, the next day, on the grid, it began to drizzle, and Carlos suddenly lost confidence. As a result, not only did he not take the fight to Renault in the race, but Alan beat him too, despite the fact that he wasn’t at his best, having been knocked about a bit in a punch-up in Putney High Street a few days before. I think the stark contrasts in that anecdote sum up the differences between their characters.

“Keke had a fantastically athletic ability to drive an F1 car quickly”

“But don’t get me wrong: Carlos could do amazing things. He used to learn circuits in stages then back off for part of the lap while he had a think about it, visor up, as a result of which his lap times were very slow at first. It used to drive Patrick mad. Then, after a while, having driven each section fast in isolation but not having strung them together to record one fast lap, he’d decide that the time had come, and he’d suddenly put it all together and the result would be a fabulously quick lap. But he faded on too many race days. Nowadays you’d probably suggest a sports psychologist, but that wasn’t really a thing 45 years ago, certainly not in F1 anyway.

So,,, who designed the McLaren 4/4?

“Also, because Frank and Patrick were so matey with Alan, Carlos began to think that they wanted him, Alan, to do the winning. Actually, we just wanted to win, and we didn’t really mind which driver did the winning. I guess you’d have to say that the environment in the team didn’t really suit poor Carlos, and he struggled with the kind of setback that Alan would just shrug off. For example, Carlos was devastated when we switched from Michelin to Goodyear in the middle of the 1981 season. To be honest, I think about Carlos a lot, even now. In fact I might even say that, as his engineer, my inability to create an environment in which such a brilliant driver could really deliver has been disturbing me all these years.”

Reutemann abruptly retired after just two grands prix of the 1982 Formula 1 season – perhaps the onset of the Falklands War had made such a patriotic Argentine unwilling to continue to race for a team so defiantly British – and, as a result, Williams’ drivers that year would be Keke Rosberg and Derek Daly. “Keke was intelligent and combative, and actually one of the reasons we hired him was that Carlos had said that he had ‘the best car control I’ve ever seen’. And he was right: Keke had a fantastically athletic ability to drive an F1 car quickly. But he didn’t have the reserve mental capacity that certain other racing drivers had to think about the totality of the task. That’s why he was often to be seen scratching his head at McLaren, where he was comprehensively beaten by Alain [Prost].”

Oatley with Senna, ’90,

Getty Images

Oatley left Williams in 1984, joining Carl Haas’s Beatrice F1 team. Why, I ask him? “Well, because they asked me,” he replies, smiling. “I was offered a job. Also, I felt I should try to prove myself on my own, without the safety net that was working with Patrick. OK, it didn’t work out for any of us really, but we were a good bunch: there was Ross [Brawn], Adrian [Newey], Alan [Jones], Patrick [Tambay] – some top people. If we’d had more time to try to make the team develop, I think it might really have been something. But we didn’t and in 1986 I joined McLaren.

“That came about because our [Beatrice] cars were quick in Hungary in 1986 – Patrick qualified sixth and Alan qualified 10th – so Creighton [Brown], who worked for McLaren, approached me in the Hungaroring paddock and asked me if I’d be interested in discussing a job. A couple of months later I rang the doorbell of Ron’s [Dennis] house, which some used to say was the most expensive bungalow in the UK once Ron had finished renovating it. Gordon [Murray] opened the door. I signed the contract there and then, and I’ve been at McLaren ever since.

laddies in red, from left, Steve Nichols, Ron Dennis, Gordon Murray and Oatley, Adelaide, 1989

“Ron was fantastic: hard-working, hands-on, ambitious, supportive of his staff, and a real racer. I worked closely with Gordon and Steve [Nichols], and they’re both good friends of mine to this day. But they didn’t really get on with each other, sadly. I think Steve was upset when Ron hired Gordon. It sometimes happens like that, and such situations are never easy, but Ron wanted a big name.”

“Which of them designed the all-conquering McLaren MP4/4 that won 15 out of 16 grands prix in 1988?” I ask.

“I’m not going to get into that,” Oatley replies, grinning. The reason for my question is that Murray and Nichols both lay claim to that all-time-great F1 car’s authorship, so, matey with both men, Neil can be forgiven for not wanting to answer my question. But, in case you are interested, it was Nichols. That is what McLaren legend Tyler Alexander used to tell me. That is good enough for me.

Oatley and clipboard, with Prost’s car, Rio, 1987

Grand Prix Photo

“One person who definitely didn’t design the MP4/4 was me,” says Oatley with typical modesty. “But I was chief designer [and then executive engineer] from the MP4/5 [of 1989] onwards, right up to the MP4-17D [of 2003].” That 14-year period encompassed dozens of McLaren glory days – and F1 constructors’ world championships in 1989, 1990, 1991 and 1998, and drivers’ world championships in all those years and 1999, too. I attempt to persuade Oatley to blow his own trumpet about that incredible period of Woking success, but he will not do it. “Great team effort,” he says, and he leaves it at that.

About Alain Prost and Ayrton Senna, however, he is prepared not only to wax more lyrical but also to impart an insight about their interactions that I find devastatingly revealing of the complex coils of both their characters: “It was an enormous privilege to work with them – two truly brilliant drivers obviously – and having both of them in our team at the same time was amazing. From an engineering point of view, and from a psychological perspective too, I found it fascinating that their car set-ups were always so similar: just tiny variations of suspension and wing settings usually, but no more than that.”

Kimi Räikkönen ought to have more world title

“Why was that, do you think?” I ask.

“Well,” Oatley continues, “I’d put that down to a strange fear that they both felt. What I mean is: Ayrton was convinced that he could drive the same car faster than anyone, including Alain, and Alain was convinced that he could drive the same car faster than anyone, including Ayrton. As a result, they were both super-anxious not to lose out by deviating in set-up from what the other had. In fact, so concerned were they both that they might lose out in that way, that they both refused to explore set-up variations that might, perhaps, have given them an advantage.”

“We should have won the 2003 and 2005 championships with Kimi”

The next McLaren world champion with whom Oatley would work was Mika Häkkinen – “perhaps one of the great underestimated F1 world champions”, he says. “He was very, very fast and he was tremendously brave and skilled. He was also extremely focused and dedicated, which qualities he deliberately kept below the radar, because he was never one to sing his own praises. In particular, he was always super-enthusiastic about trying out new technical developments, and he was always super-ready to adapt his driving style to optimise any available performance gain that they might confer. He was great.”

“And Kimi [Räikkönen]?” I go on.

“Well, Kimi was just Kimi: brilliantly talented and naturally quick. We should have won the 2003 world championship with him and the MP4-17D, because we should have realised earlier that the MP4-18 wasn’t going to make it. It never raced, as you know, but, with hindsight, we carried on trying to make it work for too long. After a while I refocused on the MP4-17D, but I did all my design modifications by hand, simply because I wasn’t from the CAD [computer-aided design] generation, so that slowed down its ongoing development a bit.” As if-only stories go, it is a particularly frustrating one. Räikkönen missed out on the F1 drivers’ world championship by just two points that year. Had the MP4-18 been jettisoned earlier, and had greater resource been invested in the development of the old MP4-17D, the performance dividend would surely have amounted to more than those two points.

Eagle T1G, Oatley’s favourite Formula 1 car

Getty Images

If Stirling Moss, Graham Hill and Bruce McLaren were Oatley’s three childhood heroes, which F1 car is his all-time favourite? He pauses for thought. “Well,” he says, “I’ve got a one-eighth-scale model of Dan Gurney’s Eagle T1G in my garage. That was such a beautiful car.” It so happens that, when I once asked Ron Dennis to name the F1 car that he thought most aesthetically pleasing, he answered uncharacteristically quickly and succinctly: “Eagle T1G.” Great racing minds think alike.

Does Oatley have any regrets? “Yes, not winning three world championships that we should have won. The first is the 1981 F1 drivers’ world championship. OK, we [Williams] won the constructors’ that year, but we should have won the drivers’ too, with either Carlos, who ended up second, beaten by just a single world championship point, or Alan, who ended up just three points behind Carlos. And we should have won the 2003 and 2005 championships too, with McLaren and Kimi, but we missed out on the drivers’ and the constructors’ in both those seasons, when we should have nailed them.”

“One last question please, Neil: do you plan to retire at some time in the not-too-distant future?”

“Oh no. I have absolutely no plans to stop. I love it. It’s a vocation – a hobby that turned into a career.” Believe me: Neil Oatley really is the ultimate F1 ‘lifer’, and his career, which is ongoing, has been, and continues to be, a truly great one.

Born: 12/06/1954, Camberwell, London

- 1976 Graduates at Loughborough Uni.

- 1977 Joins Williams Grand Prix Engineering as a design draughtsman.

- 1978-79 At Williams becomes race engineer to ageing Clay Regazzoni.

- 1980-81 Race engineer to Carlos Reutemann who finishes third in the F1 championship in 1980 and second in ’81.

- 1985-86 Recruited to Beatrice (Haas) where he becomes chief designer, working on the THL1 and THL2 cars.

- 1986 Moves to McLaren to work with Gordon Murray and Steve Nichols.

- 1988 Project lead for the normally aspirated V10 project, then the MP4/5.

- 1989 McLaren’s Alain Prost is the F1 drivers’ champion with the MP4/5; McLaren is the constructors’ champion.

- 1991 Ayrton Senna wins F1 world title; McLaren has won four consecutive drivers’ and constructors’ titles.

- 1998-99 Mika Häkkinen wins back-to-back F1 world championships.

- 2003- Project manager in F1 engineering programmes; involved with IndyCar, Xtreme E and WEC projects.