Oscar Piastri is probably the next F1 champion, thanks to a dose of Aussie grit

Australia is never far from a major sporting triumph. Paul Fearnley reckons there’s another on the way – in F1. Here’s why it happens…

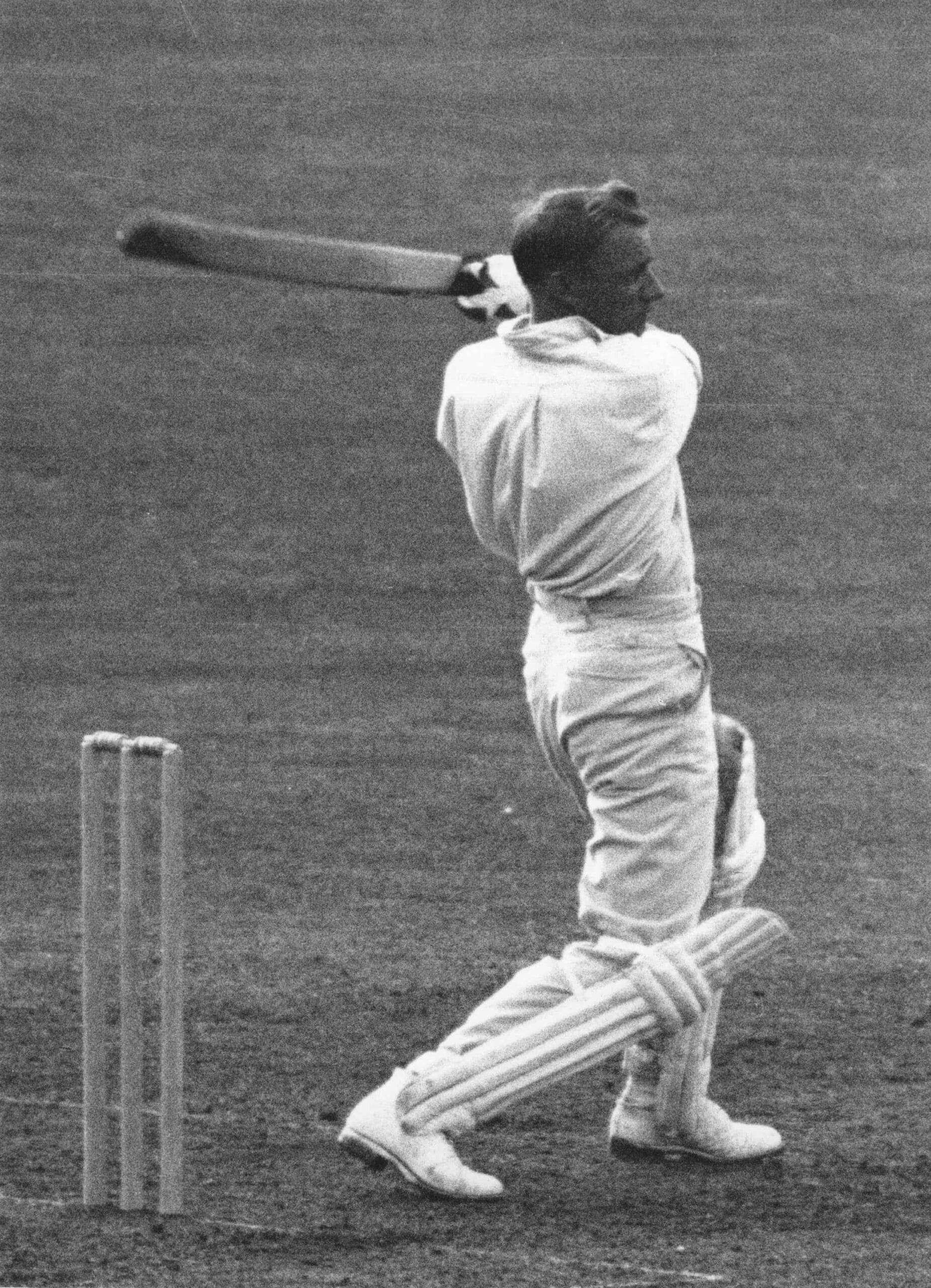

Cricket’s inaugural Test of March 1877 set the tone. An England party that was already exhausted by a hectic schedule – this match in Melbourne was to be the 19th of its tour – was reeling still from a rough six-day crossing from New Zealand. Selection, therefore, was straightforward: all 11 available ‘fit’ men played.

Underdog Australia was immediately on the front foot when opening batsman Charles Bannerman, born in Woolwich, made a gritty century. Then opening bowler Tom Kendall, born in Bedford, took seven wickets in England’s second innings to strand the visitors 45 runs shy of their target.

The bickering between the New South Wales and Victorian associations – ace fast bowler Fred ‘The Demon’ Spofforth had refused to play – was forgotten, as a country of two million united and exalted in sport.

Australia, 55th in terms of global population today (27 million), has been batting above average in cricket – and cycling, golf, hockey, netball, rugby, swimming and tennis – ever since. None of which are its most popular sport. That’ll be Australian Rules Football.

It lays claim to the greatest Test batsman by a quantifiable 38 percentage points: Don Bradman. And to the only man to complete two tennis grand slams: Rod Laver. To the most successful female tennis player: it’s three grand slams for Margaret Court. To the greatest rugby league player: Cameron Smith. To the only athlete to win individual Olympic gold at 100m, 200m and 400m: Betty Cuthbert. To the world’s greatest miler: Herb Elliott: unbeaten in 36 races, retired at 22. And to the first swimmer (of only four) to win three consecutive Olympic golds in the same event: Dawn Fraser.

Then there are the team sports. World Cups in: cricket (50 and 20-over varieties) – seven for the men, 13 for the women; rugby league – 12 for the men, three for the women; netball (12); hockey – three for the men, two for the women; and rugby union – ‘just’ two, for the men. Oh, and 28 Davis Cups and seven Federation Cups in tennis. Plus an America’s Cup and a Tour de France.

As for Formula 1 – another team sport geared around an individual – Oscar Jack Piastri’s grand prix victory in Spain marked the 50th for an Australian driver: ranking seventh (of 23) by country. Should he win this year’s world championship – upgraded from possibly to probably – it will be the fifth for an Australian: ranking jointly fourth (of 15 countries).

Certainly, he has inherited/been imbued with the national knack, having arrived on the back of an unprecedented hat-trick of junior titles from 2019: Formula Renault Eurocup, and FIA’s F3 and F2. Blending the mulish monasticism of Jack Brabham with the bullish machismo of Alan Jones – and benefiting from the grit, wit and wisdom of Mark Webber in his corner and ear – he fears no one, backs himself, learns quickly and makes tough decisions (witness his controversial split from Alpine in 2022) as well as being tough to pass. Max Verstappen is impressed. It takes one to know one.

So what puts those from Down Under so often on top? A favourable year-round climate helps. As does a culturally diverse population: Piastri has Italian and Chinese ancestry through his father, and Scottish and Irish through his mother.

Then there’s the sense of identity and worth that global sporting prowess bestowed upon a country that was both remote – those 1877 tourists set sail on a six-week voyage in the September of the previous year! – and young: Australia wasn’t federated until 1901.

And success breeds success – as well as that equally powerful, when channelled positively, driving force: the fear of failure. There was a national outcry when the latter became a stark reality. Australia won just five medals – and not a single gold among them – at the 1976 Montreal Olympics. Whereupon professionalism – public and private financial support, scouting, coaching, conditioning – was quickly bolted to all the good that had gone before.

The Australian Institute of Sport has been churning out star performers – from archers to water polo players – since its opening in 1981.

Motor sport does not fall within its wide remit – though its wheelchair basketball players have benefited from Formula 1-type carbon-fibre technology. Besides, the bewildering infrastructure of a modern F1 team like McLaren belies a historical, fundamental self-sufficiency.

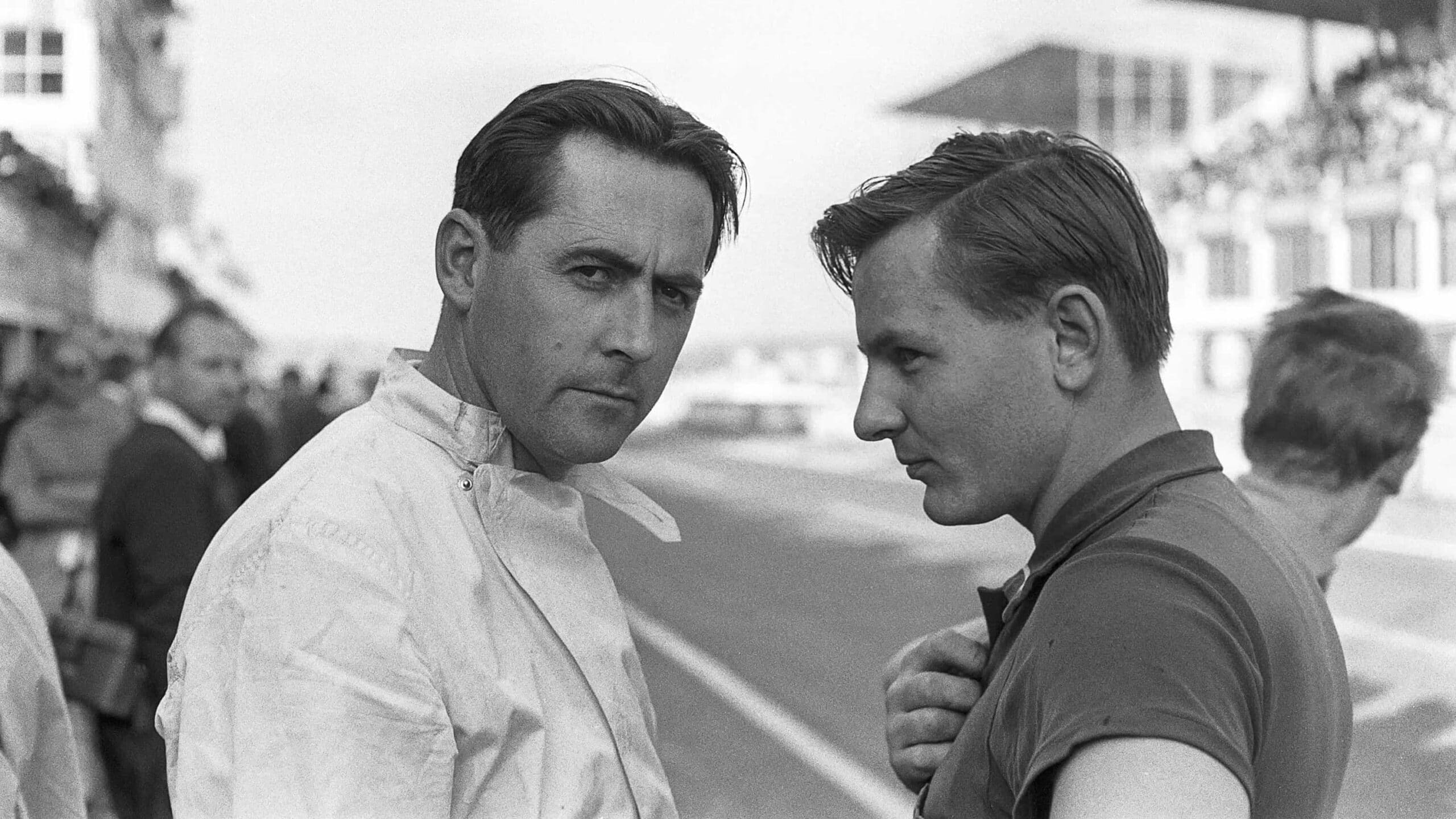

When Brabham bade farewell to wife Betty and young son Geoffrey to base and race in England, it was too much to give up and too far too travel – by Qantas four-prop Super Constellation – to fail. Quickly realising what those Australian cricketers had discovered in 1877 – that they were as good if not better than the next bloke – he soon went his own way.

With vital input from Gillingham-born Ron Tauranac, of French extraction, whom he had met in the small but thriving, insular and therefore inventive Australian motor sport scene of the early 1950s, he turned the sport on its head by winning two world championships in a car with its engine behind the driver, and a third in a car bearing his own name – prominent on its nose, not just along its cockpit’s flanks.

Brabham the team was the blueprint for F1’s kit-car era – Jack, using his reputation and contacts to build an organisation underneath him, brought Goodyear and Hewland to the party – to which Australia’s next world champion would aspire.

Jones arrived in England – via passenger jet at least – in 1969 with £75 in his pocket, and sold second-hand minivans in order to go racing. He and wife Bev would run a boarding house for backpackers in Ealing to sustain that dream during a tortuous junior formulae journey that eventually led to the fringes of F1: privateer Hesketh; number two at fledgling Hill; and number one at floundering Surtees.

In part because of this, he proved to be just the sort of no-nonsense racer that like-minded Frank Williams and Patrick Head needed and wanted. Jones’s influence on the team they created would be felt long after his (premature) 1981 retirement.

Yet both Brabham and Jones had briefly considered going home for good. Webber was facing a similar dilemma when a neighbour/family friend from Queanbeyan (population: 37,500) – who just happened to be David Campese, the greatest rugby union winger – (goose) stepped in with a £40,000 loan/lifeline.

Connections. The formative Brabham and Tauranac lived 90 miles apart, a two-hour hop/skip/jump in Oz topological terms, with much to draw them together and little between to keep them apart. Until, that is, Jack left for England. Ron, until he joined him in ’60, had to send design ideas by post.

Departing Jack sold his beloved Cooper-Bristol – a decision he was soon to regret but quickly recover from – to Stan Jones, Alan’s racing father. And Stan knew Ron, who would help Alan out with F3 Brabhams.

Australia is blessed with mid-sized communities (50,000-100,000), which are elite sporting hothouses. Urban, but with rural on the doorstep. Big enough to provide varied opportunities – even Queanbeyan has two rugby league clubs, two football teams, and one each for Aussie Rules, cricket, hockey and rugby union – without offering the infinite distractions of a metropolis that tempt away/peel off talent or obscure it until it’s lost.

Matters have been different for Piastri in several ways. For one, his family was sufficiently wealthy so as to be able to help steer him through a more regimented progression. But still he packed his bags and upped sticks, admittedly in a shrinking and more connected world, to the UK and to Europe as a 15-year-old to hone his racecraft.

Plenty of talent, a bit of grit – and surely some of the above must have rubbed off on him. And F1 is now his oyster.