F1’s most successful female racer: Was Lella Lombardi too far ahead of the times?

Lella Lombardi is unique, being the sole female to score in the F1 World Championship. As Jon Saltinstall reveals, she faced her career with quiet determination and kept her personal life away from the press

Getty Images

It’s a popular quiz question – “Who is the only woman to have scored points in an F1 grand prix?” Some of the more pedantic respondents will indicate that it was actually only half a point, as the race in question was stopped early, but either way, by finishing sixth in the 1975 Spanish Grand Prix, Lella Lombardi became the holder of that unique statistic. However, what is equally clear is that the record does her a disservice, as it overshadows the rest of her 23-year career.

Lombardi in the Scuderia Italia Brabham, first race of the 1973 Italian F3 season at Casale.

McKlein

Italian national F850 champion in 1970; the Ford Escort Mexico Kleber Challenge title in 1973; sharing the highest-placed finish post-war by an-all female crew in the Le Mans 24 Hours (with Christine Beckers in 1977); three outright victories in the World Sports Car Championship, followed up by 13 class wins in the European Touring Car Championship and the 1985 Division 2 ETCC crown (with Rinaldo Drovandi) – that’s a pretty impressive record for any driver. These were among her other achievements, yet they are largely forgotten, eclipsed by the focus on F1 that tends to overlook other areas of the sport. There was a great deal more to Lella Lombardi than her points-scoring result in the 1975 Spanish Grand Prix – even if by doing so she achieved something that two-thirds of the men who started an F1 race never managed.

F850 win at Monza, 1970

Claudio Zancai

On the rise, 1972

McKlein

Given Lella’s impressive record, and her significance to the sport for gender-obsessed F1 statisticians, it has baffled me for decades as to why there has never been a biography written about her, not even in her native Italy. It’s something I have wanted to put right for a long time, so when I was offered the opportunity to write about “whomever I wanted”, I jumped at the chance. Quickly it became apparent why nobody had attempted it before. Lella gave few interviews during her lifetime and largely kept herself to herself. Her career spanned 1965 to 1988, and for a devout Roman Catholic from a then traditional Italy, the fact that she was also gay meant that she built a defensive wall around her personal life. Fundamentally, this was to protect her partner Fiorenza, who was a constant presence alongside her from the earliest days of her career, and (along with Lella’s siblings and with help from a hire-purchase deal) provided the financial input to help her acquire her first racing car, an F875 CRM, with which she learned the ropes in the new Formula Monza that was launched in 1965. So effective was Lella’s guarding of their life together that many of the Italian journalists who knew the couple well enough to be invited for dinner at their home never knew Fiorenza’s surname.

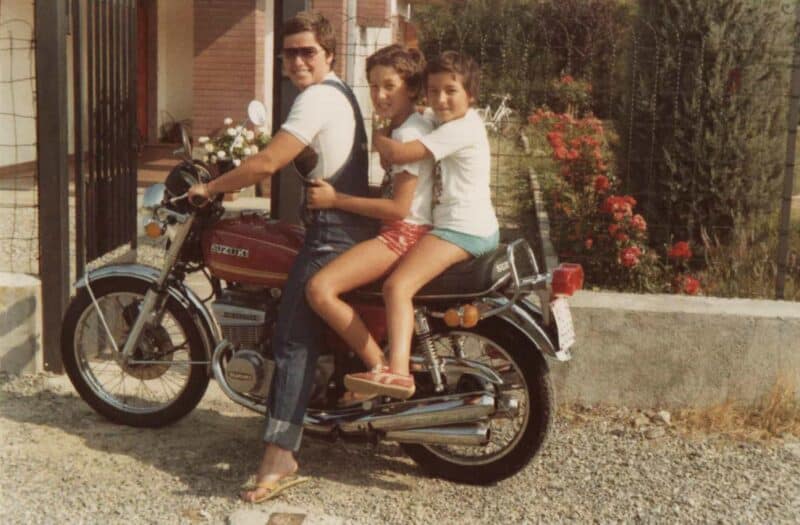

Our heroine, 1975, with a friend’s children – on the day she had signed an F1 deal with March

Giuseppe Bonadeo

Her background was unusual for a racing driver, even in car-mad Italy. Her father was a butcher in the tiny village of Frugarolo, close to Alessandria. A practical rather than an academic pupil, she was a natural athlete and became a capable handball player. She learned commercial skills from her father, negotiating with traders at the meat markets, while developing a taste for competition by racing her Lambretta against the village boys. This resulted in a visit from the local priest, asking her to tame her wild ways. Although she was the youngest of three children, Lella became the first person in her whole family to hold a driving licence, learning at the wheel of the firm’s van. Friends tell eyebrow-raising stories of their adventures making deliveries on the Ligurian peninsula.

Smiling and cheerful out of the cockpit, Lella was always informally dressed; you’ll struggle to find a photo of her in anything other than racing overalls, and in those where she is in civvies she’s usually wearing jeans and sweatshirts. It therefore came as a surprise to discover that before she became a racer, she was an accomplished dancer. As a teenager, she and her friend Giuseppe Bonadeo won many local and regional jive contests. Discovering an image of Lella in a party dress was almost disconcerting!

Lombardi, European F5000, Brands Hatch, 1974

It was also interesting to learn that, away from the racetrack, her favourite pastime could not have been further removed from the sound and fury of her sport. Her friend Oscar Berselli, right-hand man of her benefactor Count Gughi Zanon, tells how “Lella really liked fishing; it helped her relax and she went as often as she could. On any weekend she had free she went fishing with Fiorenza, who couldn’t go during the week because she was busy every day in the office at the Davoia insurance agency that she and Lella ran as a business partnership.”

She was good at finding and maintaining relationships with sponsors and was no diva; her backers quickly realised that she did her best to give them a good return on their investment. Brands Hatch’s Angela Webb recounted how she would not squander their cash on extravagant hotels or first-class air tickets.

In 1974, John Smailes wrote in Sports Car World, “While the top men in the sport seek the trappings – the glamour, the parties, the easy chances, the money – she’s motivated by none of them. It’s almost as if she has been consecrated into the religion of motor racing. She is married to her sport.” Had she raced two decades later, Lella might have been able to attract still more lucrative sponsorship that could have put her in more competitive cars; attitudes were starting to change – one could argue that she had helped to change them – but she probably saw few of the benefits herself.

Lombardi was purely focused on her racing career – there were no champagne-fuelled parties or throwing money around

Getty Images

Bonadeo reflects sadly, “The Italian mass media gave little space to Lella’s exploits. Perhaps in the Alessandria area some news came out, but at a national level not much at all. When they interviewed Vittorio Brambilla, they might talk about Lella then. However, in England there was much more written about her than there was in Italy. Perhaps it was a mistake on our part in not giving her enough prominence; she was too far ahead of the times.”

“Lella’s career during the 1960s and 1970s was hamstrung by misogyny and inattention”

What is equally clear, however, is that despite her talent and tenacity as a racer and the quality of her technical feedback to her engineers, Lella’s career during the 1960s and 1970s was hamstrung by a combination of misogyny and inattention on the part of some team owners and race organisers. In one of her rare interviews, she told how she hated the condescending smiles she received from some male rivals at the start of her career, which conveyed either contempt or the patronising suggestion, “I’ll help you because you’re just a woman who won’t be able to do this alone.” In her F3 years, she also told her friend, Mirosa Vaccotti, “These men don’t give me a break; when I go slowly, they say I’m an obstacle; when I go fast, they say I’m dangerous. They don’t want me there!” It was a rare complaint from her about the way she was treated by her male rivals.

A top-six finish for Lombardi in the 1975 Spanish GP gave her half a point in the F1 World Championship but the race is remembered for the accident that cost the lives of four bystanders

Getty Images

When she eventually reached F1, in mid-1975, frustrated with her March’s perpetually inconsistent handling which showed no improvement regardless of any set-up changes, she was untypically forthright to Autosprint: “I honestly think that the car is not up to the task. My team tends to give me the leftovers from others and the car is rarely as good as I would like it to be.”

Lombardi’s first F1 outing was the 1975 South African GP, driving for March (DNF)

Getty Images

It’s a criticism that her team-mate Hans-Joachim Stuck confirms to be true, especially with regard to the down-on-power engines with which she was often saddled. There is also the well-documented story that the reason for her car’s mysterious handling only came to light when her successor at March, Ronnie Peterson, reported the same issue when he was given Lella’s former chassis to drive in 1976. When the tub was stripped down at the factory, a cracked internal bulkhead was found to be the culprit, by which time the damage to Lella’s F1 season – and her reputation – had been done. Some years later, in this magazine, March technical chief Robin Herd admitted, “Poor Lella, she’d had bad traction all along. I feel sorry for her and wonder about it even now. It was one of the few times that she complained about the inequality of F1 – because nobody had listened to her about the problem with the car.”

“Poor Lella, she had bad traction. Nobody had listened to her about the problem with her car”

Gender was something that never concerned her. After making her F1 debut in 1975’s South African Grand Prix, she told a local reporter, “I hope that, now, people have begun to understand that Lella Lombardi is a racer who is a woman, rather than a woman who races. That is a distinction that I care about very much.” Later that year, in a Q&A column in Autosprint, she claimed, “I have never considered the male-female issue, only the competition that exists between different drivers. Under the helmet, women and men are completely equal.”

All female team at Le Mans, 1977.

Getty Images

Class win, Spa 24 Hours, 1984

Jean-Claude-Legrand

When asked by the New York Times about her historic F1 points finish, she responded, “I don’t think it dawned on me that I was the very first woman to collect championship points. Things like that just don’t bother me. I’m just as competitive as any man. Too many women perhaps feel that motor racing is essentially a masculine affair. Well, I don’t agree at all. It’s simply a competitive sport. There’s a lot of glamour surrounding being the first girl to do well in F1, but the whole business is overrated. I love motor racing and that’s all I want to do. I’m not terribly conscious of there being a difference between male and female in this sort of thing. The thing I like is the feeling when you pass the chequered flag first. That’s something I don’t have any problems sharing with my male colleagues.”

“She was a quiet force of nature, blessed with tenacity to follow her passion for racing”

One of the recurring themes that emerged from the hundred-plus interviews I conducted while researching Lella’s story, and one of the most striking, is that nobody I spoke to or who commented about her in contemporary accounts has a bad word to say about her. This is extremely unusual in any walk of life, but especially so in the dog-eat-dog world of professional motor sport where feelings and opinions are amplified by rivalry. It’s clear that she was a quiet force of nature, blessed with tenacity and a determination to follow her passion for racing above all else. Equipped with an iron will, making great personal sacrifices despite limited financial resources, she fulfilled a dream she had nurtured since childhood. Her technical ability is mentioned repeatedly, often in the same breath as her quite demanding set-up requirements from her mechanics. She also possessed excellent mechanical sympathy and was adept at looking after the car. Seventeen career pole positions and 20 fastest laps confirm she was no slouch when it came to speed, either.

Lombardi, left, and Christine Beckers finished 11th

at Le Mans ’77

Getty Images

The ups and downs of Lella’s career, with some challenges overcome and others providing career-damaging setbacks, read like a Hollywood film script. It’s one that also has a tragic ending. Having formed her own team, Lella Lombardi Autosport, to create opportunities for new drivers, ill health forced her to retire from racing in 1988. The pain she thought was due to a sailing injury turned out to be breast cancer, and she passed away peacefully in Milan in March 1992, at just 50.

1980 Vallelunga 6 Hours driving an Osella PA8

Gianni Tomazzoni

In an obituary for Autosprint, Franco Lini wrote, “Lella only wanted to satisfy herself, no one else; to compete not as a woman against men, but as driver against driver. And she committed herself to it thoroughly. She was convinced that it was only one’s approach to racing that made the difference, if one had the right machinery. She made racing the sole purpose of her life, and she was fully satisfied, knowing that what she had achieved had always been the maximum possible with the means at her disposal. This is why she lived a happy life.”

Lella Lombardi: The Tigress of Turin – Her Authorised Biography by Jon Saltinstall, will be published by Douglas Loveridge Publications later this year.