A very fine fellow...Innes Ireland

Innes Ireland at the 1962 Crystal Palace Trophy

Central Press/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Robert MacGregor Innes Ireland was one of life’s outstanding characters, whose boisterous personality earned as much popularity as it brought him trouble in 63 years. The expression ‘doughty fighter’ might specifically have been coined for him.

Though he was always known as a Scot, he was actually born in Yorkshire on June 12 1930, his father moving the family to Kirkcudbright when he was two. Perhaps that heady mix of bloodline and upbringing explains much of the colour Innes brought to his interpretation of living.

When he was 12 he came to what he described as his first ‘cross-roads of fortune’. During one of his favoured walks in the Scottish countryside he befriended the chauffeur of an elderly lady at Newton Stewart. He duly familiarised himself with the workings of her Bentleys, and he became friendly with her too. For Christmas in 1942 she gave him a copy of Sir Henry Birkin’s biography, Full Throttle, and his passion for motor racing was sparked that day.

He bartered a cherished .22 air rifle for an Ariel 500, and his enthusiasm went up another notch, just as his academic career went into final decline.

He and brother Alan, having dominated sports at Kirkcudbright Academy, then moved on to motorcycles. When Innes was 15 they bought a 17 year-old Rudge 500, and this coupled with spells at the wheel of his elderly friend’s 3-litre Bentley, taught him the rudiments of controlling vehicles. At times the unkind would suggest that another year might have helped! Later he bartered a cherished .22 air rifle for an Ariel 500, and his enthusiasm went up another notch, just as his academic career went into final decline. His father was by now realising that the chances of his younger son following in his footsteps as a veterinary surgeon were precarious, and his interest in engineering led him instead to an apprenticeship in the Aero Engine Division of Rolls-Royce in Glasgow. There, he loved to recall, ‘I spent three happy years learning to use a file and blowing up valuable power units in the interests of science’.

It was apposite that his first motor race, at Boreham in 1952, should be the ‘Tim’ Birkin Memorial Trophy, for by now the old lady in Scotland had also willed him her 41/2-litre Bentley. In the early ’50s his racing activities were confined somewhat by the need for military service, and though he was seconded to the Paratroop Regiment, there was a little more to it than that since he had actually volunteered during a more inebriated moment.

Eighteen months in Egypt provided little more than some scares with closed parachutes and some target practice, but-on his escape from the army he set up his own business servicing Rolls-Royces and Bentleys, and bought a Brooklands Riley 9 to race. His progress up the sporting ladder was swift and decisive, helped in 1956 by another of those fortuitous meetings when he made the acquaintance of Major Rupert Robinson. Together they went half shares in a new Lotus XI, and thereafter Innes never looked back. That year – after shunting the car first time out! – he won the club racing world’s Brooklands Memorial Trophy, and a drive with Team Lotus in the Swedish GP for sports cars. An invitation to join Ecurie Ecosse followed for 1958, together with 15 victories. That in turn led to a works drive for Team Lotus in 1959, and suddenly, despite grave misgivings on the grid, he had taken fourth place on his Grand Prix debut in Holland.

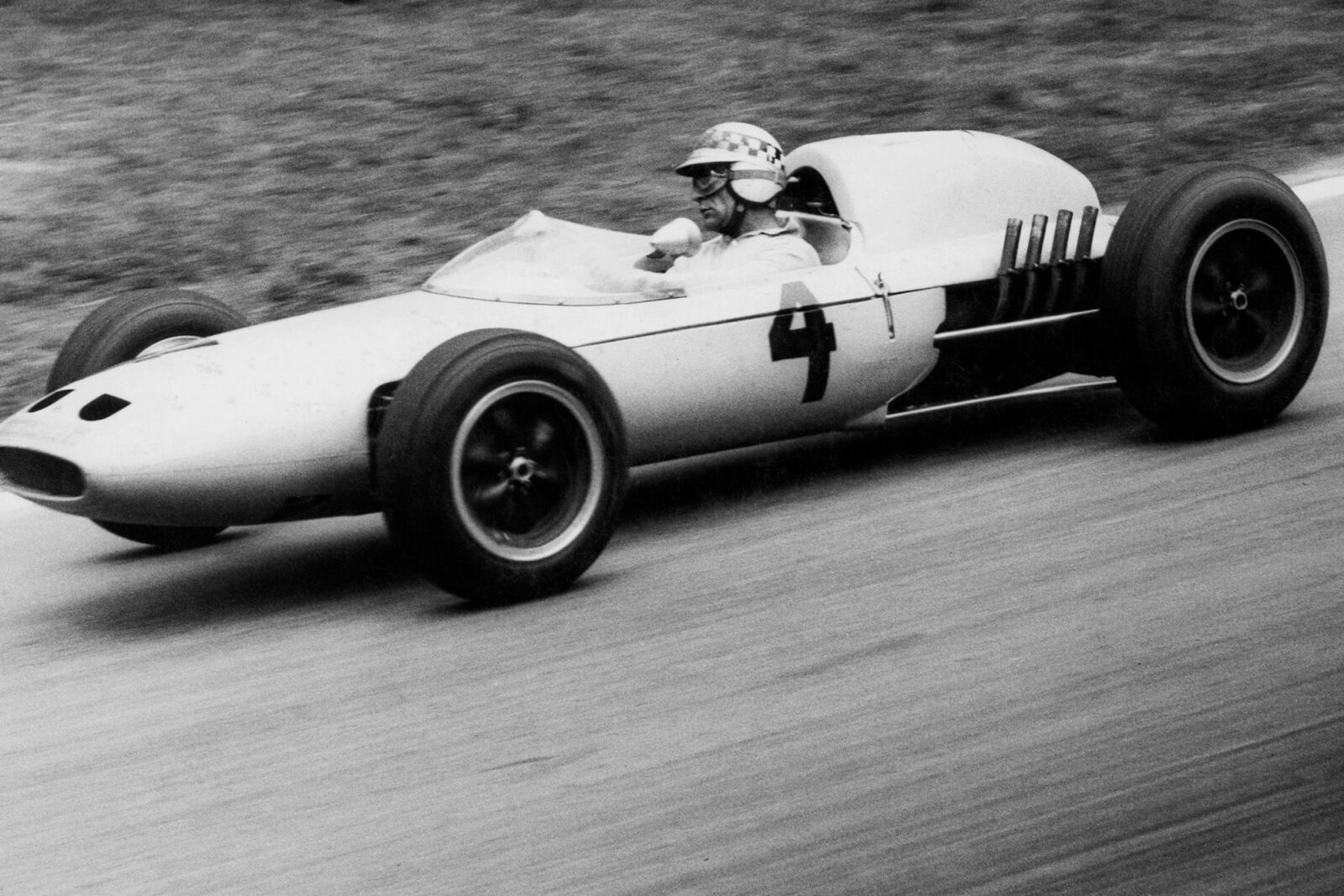

Ireland on his way to a victory in the non-championship race at Solitude in 1961

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

The following year, in the boxy new Lotus 18, he beat close friend Stirling Moss at Goodwood and Silverstone, and at the end of 1961 crowned a successful season by winning the US Grand Prix at Watkins Glen. Moss, of course, had already won races for the marque, but this was Team Lotus’s own first victory of its current tally of 79. It was the climax of his career, and a championship challenge loomed for 1962. Then came the bombshell when Colin Chapman dropped him in favour of his young teammate, Jim Clark.

The manner in which Chapman had broken the news was harsh: Innes learned of his dismissal at a motor show, through a third party. For many years after that he harboured uncharitable thoughts about Clark’s role in his downfall, believing that Jimmy had in some way conspired to have him removed. It was typical of Innes’s honesty that he was big enough to admit later that he had completely misjudged Jimmy’s character. The decision was purely Chapman’s. One of his abiding regrets was that he had never fully made his peace with Clark before the younger Scot’s untimely death at Hockenheim in 1968. By that time Innes had become the erudite sports editor of Autocar, and his tribute to Clark was eloquent and deeply moving. His brand of journalism was always of the tell-it-like-it-is variety.

Innes alongside Clark at Syracuse in 1961. To Innes’ regret, he never fully made his peace, having mistakenly blamed his fellow Scot for his departure from Lotus before the 1962 season

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

On the track Innes was a fearless but scrupulously fair competitor, whose sheer speed, and the fragility of his machinery, often led him to and beyond the brink. He crashed often, but it wasn’t always his fault. The bad one in the Monaco tunnel in May 1961 most certainly was, for he selected second gear instead of fourth because he’d momentarily forgotten that the ZF gearchange gate was reversed on the Lotus 21. Later he would remark laconically: “I came out of the tunnel without the car.” Then there was the accident at Kent, Seattle in 1964. He sustained serious hip injuries when his Team Rosebud Lotus-Ferrari sportscar left the track and struck a parked car. Knowing he was going off the road he was trying to control where the Lotus ended up and knew that the other car was there, but its owner had moved it slightly since the previous lap . . . On that occasion his allergy to morphine obliged him to suffer the pains of hell as they gently cut him from the wreckage.

Interviewing him for Motor Sport back in late 1975, Alan Henry made the error of beginning what would become a very warm relationship with the words: “You used to crash a lot, didn’t you?”

Innes had replied: “We don’t know each other frightfully well, do we, lad?” and would many years later remind him of that faux pas when he signed Alan’s copy of his autobiography All Arms and Elbows. Typically, he had taken it away with him because he wanted to think about the inscription; when he returned it there was the beautiful copperplate writing and an endearing message reminding Alan that it’s best never to begin contentious conversations with men who are holding fish-filleting knives in their hand, and also expressing the humble hope that his own exploits had perhaps played a part in sparking Alan’s enthusiasm for the sport. At the time of that original interview Innes had taken up professional sea fishing off the coast of Kirkcudbright. His was the last boat home, just beating a turning tide, and as he had spotted Alan and Jenks on the harbour wall he celebrated by ‘spinning’ twice in the narrow estuary.

When he recovered from that Seattle accident it was typical that his return to the wheel should result in a triumphant appearance at Snetterton in the BRM V8-powered BRP. Sadly, however, leaving the works Lotus team had sapped his career impetus in Formula One, and though there were non-championship victories there were to be no more GP triumphs. When BRP was refused membership of the Formula One constructors’ cartel for 1965, he began a slow drift towards retirement.

Ireland (BRP-BRM) leads Mike Spence (Lotus-Climax) in the 1964 British Grand Prix at Brands Hatch

Grand Prix Photo

Looking back, he felt his non-championship win at Solitude in 1961 was the apogee of his career. “I derived most satisfaction from that victory,” he would admit, “because I was a potential winner from the start. At Watkins Glen I might have been a certain second or third but I wasn’t looking a winner all the way.”

That German triumph had been the product of commitment, aggression and racecraft as he outfoxed the more powerful works Porsches of Dan Gurney and Jo Bonnier on their home ground. The lead changed several times, but he knew that if he managed to keep it into the twisting section preceding the start/finish line there would be nothing the Porsches could do. He would laugh at the recollection of a glassy-eyed Chapman standing in the pits muttering to himself, as the Lotus sped by for the last time followed by the two German cars, ‘He’ll either win or we’ll never see Ireland again’. “The most satisfying thing about it was to see the photographs afterwards,” he told AH in that 1975 interview. “Me with a broad grin on my face flanked on either side by Gurney and Bonnier, both looking very disgruntled!” Those of us who knew him to be in the grip of the cancer that ultimately claimed him were shocked recently to see its cruel effect, for he had fought it, apparently successfully, for more than a year. When the end was clearly inevitable, the manner in which he conducted himself triggered countless thoughts of him. The stories of his derring-do off the tracks are legion, and some of them were even clean. Quite possibly many of them really were true, but in any case he was the sort about whom tales would inevitably become embroidered with each retelling by third parties. Innes enjoyed the things in life that are important to most males, and frequently indulged himself to the full.

There was the time that he ‘demonstrated’ a large Mercedes 600 at Mallory Park, only to roll it into scrap. It was the property of Mercedes-Benz UK, which was less than wholly amused when he climbed, only slightly sheepishly, from the mangled limousine. Legend has it that he then collected his black Labrador, Seal, who had also gone along for the ride, and then removed his gun from the boot with a measure of commendable sang fraud.

Chapman and Ireland at Monaco in 1961

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Apocryphal though parts of that tale may be, there was no discounting his coolness under pressure, nor his prowess with a gun, as many of us had cause to regret when stacked against him during Ford’s annual pre-Christmas clay pigeon shoot. He loved the countryside, and all such rural pursuits. Typically, his self-imposed regime of convalescence in 1964 had comprised deer-stalking and mountain climbing to strengthen his damaged legs.

Then there was the night in 1961 when he climbed a clock tower in Austria to celebrate another non-championship victory at Zeltweg, and another 26 years later when he had to be dissuaded from trying to repeat the feat when he had been indulging in another of his favourite pastimes. This was a long while after his retirement as an active racing driver, yet his continuing fitness would probably have allowed him to do it even if his sobriety at that moment had militated against it. His original feat was rendered all the more impressive in the cold light of day.

His ability behind the wheel was illustrated to perfection to a group of us in Budapest back in 1989, as he drove us to the Hungaroring circuit one morning. Ron Dennis, the McLaren chief, pulled alongside at traffic lights in his brand new Honda hire car, and the challenge was simply too much for Innes to resist. He blasted off the line, but Ron appeared not to be playing. But as Innes approached a builder’s skip, on the inside lane near to the kerb, we suddenly became aware of another car alongside, neatly boxing us in. If a final trigger had been required, that was it. A high-speed dice ensued, in which Innes’s right foot remained firmly pressed to the floor, even as he wove in and out of the copious early morning traffic. With artful precision he took on and beat Dennis, and then proceeded to do the same to Martin Brundle in his Volvo 760. The latter had seen the odd journalistic face leering at him from the car, and upon arrival at the circuit his relief was all too evident when he discovered that Ireland had been the chauffeur. Being beaten by him was respectable, even if the vehicle he had been conducting with positively indecent haste was only a very battered Lada.

Later that day I found Innes alone outside the Ford motorhome, and we had a delightful lunch together, during which it became apparent that much of what people took to be problems associated with high intake of his national product was actually fairly acute deafness, something that he would much less rather be accused of. That weekend I also interviewed him on the subject of Donald Campbell and his Bluebird, for back in 1967, upon the speed king’s spectacular death on Coniston Water, he had put himself forward to Leo Villa to carry on the quest for 300 mph on water. The idea eventually came to nothing because Innes was, by his own admission, hopeless at finding the sort of money required for such ventures, but there is no question that he would have been perfect for that daunting role. He had the courage of a lion.

In recent months he had needed every ounce of it, as he faced his illness in the same devil-may-care manner that he had always lived his life. He had married the former model Jean Howarth, who had been Mike Hawthorn’s fiancée, and together they had fought to recover when Innes’s son Jamie took his own life last year.

Several of us went to the memorial service at Chelsea Old Church. I felt a little awkward because I had barely known Jamie. It was almost as if I was intruding on another’s grief, but the genuine pleasure that Innes derived, the way his face lit up as he shook hands with us, was moving confirmation that it had been the right thing to do. His mates were supporting him, and that was what mattered.

Only a matter of weeks ago his iron will took him to his friend James Hunt’s memorial service in London, where he read Kipling’s If. He had discharged himself from hospital specifically to honour that duty, for such things were critically important to him. He had a very strong sense of comradeship.

When the mood took him, he could also be remarkably outspoken. He had no liking for Nigel Mansell, and had not been happy with the BRDC’s decision to throw a lunch in London in the new World Champion’s honour late last year. Like Hunt, he did not agree with the political double dealing that had gone on behind the scenes and did not care for the idea of a celebratory lunch, but had been overruled. As the Club’s new President he had put on a stoic face in all the pomp and ceremony. He accosted me at one point, taking my left elbow in a grip like a shark’s. “Hallo lad, how’s it going?” He was spruced up, as the event demanded, but the kilt was missing and instead he wore ordinary trousers. It struck me as unusual. I asked him why, and he responded with one of those chuckles that creased his face and lit up his eyes. “Only wear that on special occasions, lad!”

Innes Ireland was a remarkable man, garrulous, colourful, lovable – in his heyday an occasionally temperamental handful – but always the sort of larger-than-life character whose very existence enriched those around him. Beneath his rugged ‘bloody hell, lad!’ exterior lurked a highly sensitive individual who could ever be roisterous yet nevertheless conducted himself with a rare and becoming dignity.

Many years ago Michael Cooper-Evans interviewed him for a book, and was embarrassed when the subject of Lotus team-mate Alan Stacey was raised to find that, long after Stacey’s death at Spa in 1960, Innes was still visibly moved by the memory of his friend.

Like the late Denny Hulme or James Hunt, he was terrific company and a fund of entertaining stories. Our thoughts were brightened by the memories but saddened by his death as we wrote our tributes in Yokkaichi and Sydney, and now they are with Jean, and Innes’s daughter Christiane.

With his passing a part of the sport’s rich fabric has been torn away, never to be replaced, and as the motor racing world mourns there can be no greater tribute to him than that. Robert MacGregor Innes Ireland was indeed a very fine fellow, and we shall miss the sun he brought to our lives.

D J T