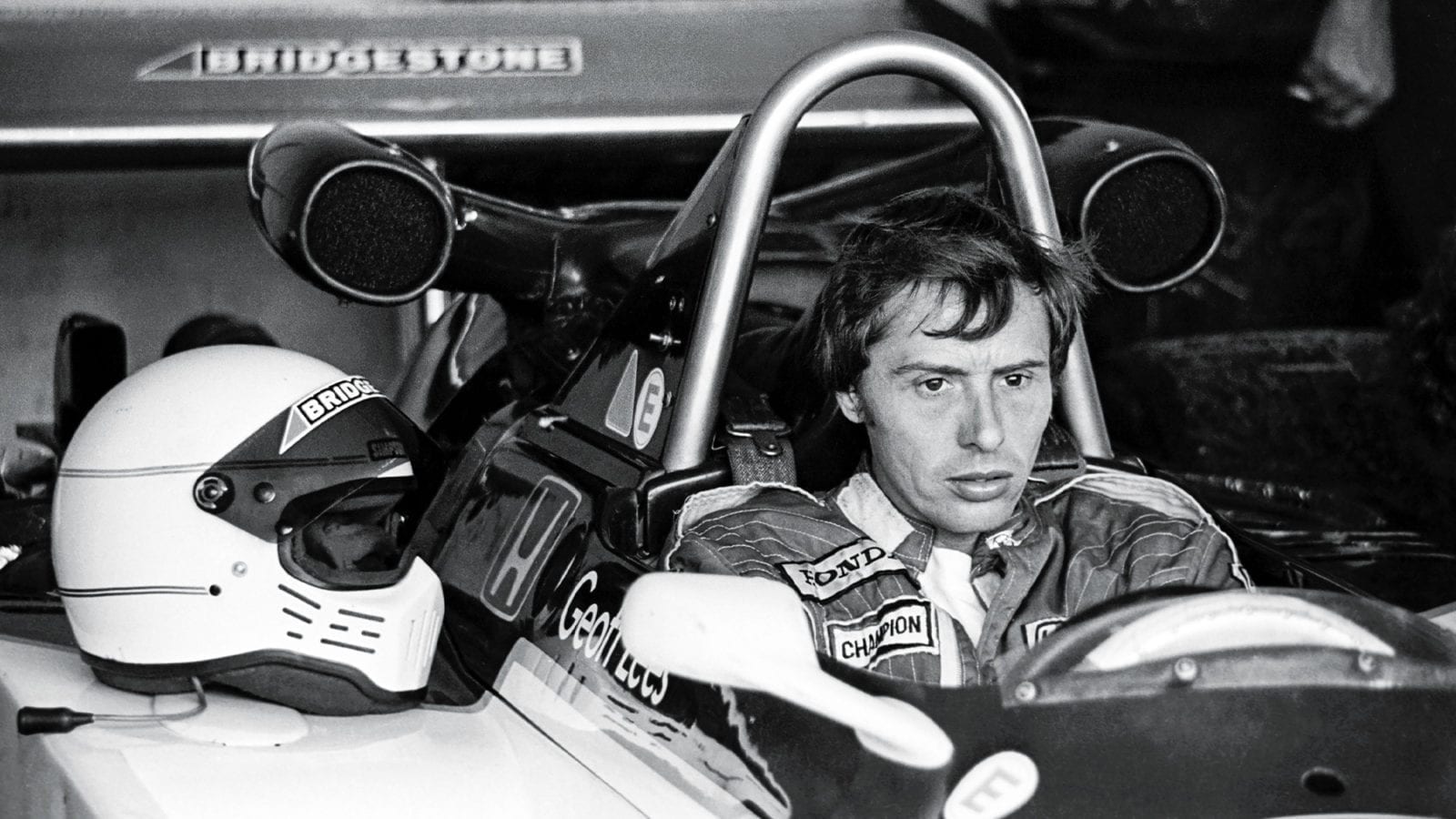

Geoff Lees: The nearly man

After seeing an F1 career snatched from his grasp, Geoff Lees turned East, earning big prizes – barring the one he craved most, says Paul Fearnley

Mike Hayward Collection

There is an accepted ladder of progression for drivers aspiring to Formula 1. In the 1970s it ran thus: formulae Ford, 3 and 2. Unfortunately, there are rather more snakes.

Even though Geoff Lees ascended all three rungs – enjoying the view from each – his eventual emulation of childhood hero Jim Clark occurred in a manner unfulfilling and in a place unexpected. For just as his misfiring grand prix career went west, the man who might have been Mansell turned east and broke new ground for his ilk: quick but lacking money and opportunity.

From the thrill of a few illicit laps – he was just 15 and wearing a “pom-pom hat” – of Silverstone in a friend’s ex-Maurice Philippe Lotus 7, it was clear to him and to others that this apprentice motor mechanic from Warwickshire possessed the knack. Clark used to carry more speed into corners than did his rivals; Lees did the same. His was a natural talent that took him to Team Lotus – albeit only once – and to within an hour of victory at Le Mans. Yet it nearly didn’t happen at all. A workplace eye injury delayed his competition debut until he was 19 and would affect him throughout.

“I had double vision for two years,” he says. “Though it came good, it has never been perfect. My left pupil is enlarged and doesn’t close down in the sun. That’s why I always wore a dark visor.”

Progress in Formula Ford stuttered initially as a result, but a win at Mallory Park in an old Alexis persuaded Lees to invest in new machinery. His patience and frugality – he restricted himself to Silverstone races in 1972 and took a sabbatical in 1973 – paid off when he swept the board in 1975 driving a Royale RP21, winning the three national titles and the Formula Ford Festival.

“I built its engine in my bedroom and won the first race,” says Lees. “After which David Minister offered me engines for the rest of the year, and Rob Roy Racing asked if it could pay my entry fees. For the first time I was getting a little team around me. Suddenly it seemed easy in a good car.”

This foundation of a 25-year career was not, however, quite as stable as one might imagine. By the time Lees had secured his deal to run an F3 Chevron in 1976, pacesetters Bruno Giacomelli and Rupert Keegan were over the points horizon. Nevertheless, he finished strongly and would start 1977 as favourite. Unfortunately, the replacement B38 was not to his liking.

“They had changed the nose and it oversteered,” says Lees. “I hate that. It’s the quick way. I’m a late braker: crazy quick – as if the corner’s not there – right up to the apex. The set-up for all my cars has been the same: turn in, grip in the middle of a corner and four-wheel slide out. That makes it easier to overtake, too.”

That’s why he enjoyed the prevailing ground-effect single-seaters on their stiff suspensions – his back has complained ever since – and why he disliked the locked diff on his Can-Am Lola. He wasn’t keen on America either, come to that. Lees did things his way.

By 1982, Lees’ F1 dreams were over. Better times lay ahead in the Far East

European Formula 2 being for the moment beyond his reach, he was surprised when a consortium of Midlands businessmen/racers, Sid Taylor, Jack Kallay of Hi-Line Car Stripes and Alfa dealer Mario Deliotti, plus Macau- based Teddy Yip, brought the offer of a drive in the inaugural Aurora AFX Formula 1 Championship of 1978. The campaign began well in a self-assembled Ensign N175 – built in Mo Nunn’s Walsall HQ and not Geoff ’s bedroom – but had fragmented by mid-season leaving Lees to pick up drives as and when. He scored F2 points at Nogaro and Misano in a Chevron.

In the circumstances, cash-rich Can-Am seemed a no-brainer. A one-off ride arranged by manager Peter Gethin with Team VDS at Riverside at the end of 1978 led to a full campaign in 1979. Lees was competitive and consistent. He was third in the championship, ahead of Keke Rosberg, despite not winning a race, but was unimpressed by the US.

“I got lost the moment I left the airport,” he says. “I saw a sign for a police station and took a down ramp. The station was atop a load of steps and I ran up them like in Rocky and opened the doors really quickly. The next thing, I had a gun stuck up my nose. The officer was helpful once he’d put the gun down but America then was not a nice place to be.”

Geoff Lees in the Ralt RH6 had three wins in 1981’s F2 championship

Lees made his surprise F1 debut in July’s German GP in a Tyrrell 009. The incumbent Jean-Pierre Jarier had caught hepatitis and Lees received a late call. This would become a theme of a fractured F1 career that spanned seven teams and just five starts across four seasons.

“I hired a little car – it’s all I could afford – and got lost because it was foggy. I didn’t arrive at the hotel until 2am and a note had been pushed under my door: ‘Breakfast at 6am.’ Ken [Tyrrell] wanted to get to the track early to sort out my seat. But the car fitted me perfectly.”

Lees qualified 16th despite having to hand his car to team leader Didier Pironi for a time, and finished seventh, having overtaken the rated Frenchman in the process. An impressive performance – neat and consistent, according to writer Denis Jenkinson – for what was to all intents and purposes a test session. “Once I’d banged wheels with Riccardo Patrese – he was a bugger for that – on the run to the first corner, I stayed out of trouble and got quicker as the race progressed. Ken was pleased and asked if I could do Austria. But on the Wednesday night before that race he rang to say that he couldn’t use me, without explaining why. I could have put my foot through the TV when I saw they’d put Derek Daly in the car.”

Lees’ Tyrrell, ’79 German GP

Shadow was a shadow of its former self when Lees joined it for 1980, and the unloved DN11 stuck him in the catch-fencing at Kyalami in March when its front suspension broke. So bad was it over the bumps of Long Beach later that month – chassis-flex causing its rack to seize under load – that he claimed illness rather than drive. There was no rush to replace him.

Switching to Ensign, he qualified for the Dutch GP, unlike local hero and team-mate Jan Lammers, only to be biffed aside by Vittorio Brambilla’s wayward Alfa Romeo. Lees’ subsequent crashing of RAM’s Williams FW07 during practice at Watkins Glen, however, was entirely his fault, having unwisely dosed on strong flu medication.

Out of the South African GP, 1980

What he needed more than anything now was a competitive car run by a strong, stable team that wanted him. That he had to step down to F2 to achieve this bothered him not one jot, for to drive for Honda, via the works Ralt squad, was too good to pass up. Lees was dismayed, therefore, to discover that not only was the powerful V6 woefully short of torque and ran so hot that it boiled the fuel – “You could hear it gurgling in the tanks” – but also that Pirelli’s tyres were inclined to blister. A quick switch to Bridgestone improved matters, as did John Judd’s eventual retuning of the engine. Lees, who had toughed it out to win at a sultry Pau, swept to victories at Spa and Donington Park before securing the title – ahead of Thierry Boutsen – with second places at Mugello, Misano and Mantorp Park.

“I settled into Christmas and waited for the phone to ring,” he says. “By January I’d heard nothing and was beginning to panic. I went for an interview for the Nimrod sports car team. This guy did not have a clue who I was or what I’d done. But I got the drive as number three to Tiff Needell and Bob Evans. That changed.”

Motor racing’s harsher realities – subbing for Lammers at Theodore, Lees had a back-row seat of Riccardo Paletti’s fatal accident in Montreal – were just beginning to dawn when John Player Team Lotus called from out of the blue. Nigel Mansell had injured a wrist in Canada and been replaced by F3 star Roberto Moreno, who failed to qualify at Zandvoort. Mansell returned for Brands Hatch – he was never going to miss his home race, especially with Lees hovering – but was hampered still and called it quits after 30 laps. Thus Lees landed his dream at Paul Ricard’s French GP.

“I jumped in, did half a lap and the engine let go,” he says. “Colin Chapman said, ‘I’m so sorry. I should have changed it [after Brands].’ He engineered my car that weekend. I was very surprised by that and it made me even more nervous. But it was fantastic, too. He was like a god to me.” Chapman had plenty on his plate. The deal to run Renault’s turbo in 1983 was announced at this race, yet Lees intrigued him.

Replacing the engine cost crucial practice laps and a fuel pump blocked by tank foam, a problem he correctly diagnosed later, cost Lees 1000rpm when it mattered most: “Colin said, ‘I’m surprised you qualified. We could hear the problem all around the circuit.’ He was happy, though, and I think I impressed by being fast in the warm-up, too.”

Lees made good early progress in the race until Tyrrell’s Brian Henton squeezed him onto the dirt on lap nine, puncturing the right-rear tyre. He would go on to set a fastest lap six- tenths better than team-mate Elio de Angelis’ best – the Italian retired after 17 laps because of low fuel pressure – and finish 12th. His late overtaking of Marc Surer’s Arrows reportedly tickled Chapman’s fancy.

“He even ran onto the circuit at the finish and threw his hat into the air,” says Lees. “People had warned me to be careful around him but he was an absolute gentleman. He invited me into the motorhome and asked me to become the test driver for the rest of the year and take over from Mansell the following season. I was over the moon. I thought I’d finally made it.”

Lees’ final F1 drive was in the JPS Lotus 91 filling in for the injured Nigel Mansell at Paul Ricard. He finished 12th

Lees insists that he signed on this basis. Nothing, however, had come of it by the time of Chapman’s December heart attack, and nor was there any likelihood of any such deal being honoured by his ‘replacements’. The dream had faded, to be replaced by Eastern promise. Back-to-back Macau GP wins of 1979-80 had got Lees noticed in Japan. The Honda link helped, too, as did his winning Japan’s national F2 title at his first attempt in 1983. But this connection ran more deeply.

“I fell in love with the place,” he says. “You could walk the streets at 2am and be safe. I needed an interpreter/guide for the first few months but after that I was on my own, living in Tokyo. Then I met and married Ayako and stayed. I fitted in, and it was nice to be wanted. Jim Clark used to jump from a Cortina into an F2 car and win in everything. I wanted to do the same. That’s what Japan provided me.”

Lees won in F2, F3000 and Group C sports- prototypes (for Toyota), and was the champion of the Fuji-based Grand Champion Series – for F3000s wearing all-enveloping bodywork – three times in four years at the decade’s end. He also did “a million miles testing”.

His F1 dream had not faded entirely. As Honda’s official tester of 1987, he set impressive times at Suzuka in a Williams FW11 hack. A sponsor was found for a third car at the Japanese GP, whereupon Honda and Williams fell out. Lotus’ spare car was exclusively Ayrton Senna’s. And though Arrows was keen, said sponsor was not.

There were other frustrations. Lees, who spoke sufficient Japanese to get him into but not necessarily out of trouble, admits to not always dealing well with local working practices: politeness and honour above effectiveness and competitiveness.

“I used to complain – a lot,” he says. “We’d have a meeting with 20 or 30 people and, rather than tackle an obvious problem, the decision taken was to ensure that someone didn’t lose face. I became sick of making the same mistakes. I’d had enough. My friend Mike Thackwell was retiring and promised to mention me to Peter Sauber. I flew to Switzerland and had this fantastic lunch before visiting the factory; I say factory, it was a private garage. I was used to driving for major manufacturers. Toyota wanted me to stay and trebled what they’d been paying me, so I stayed. It was the biggest mistake of my career. I didn’t know that Sauber was about to be taken over by Mercedes-Benz, and he didn’t tell me.”

Toyota TS010, 1992

Though the Toyota situation improved with the creation of TOM’S GB in Norfolk, under the auspices of Dave ‘Beaky’ Sims and Glenn Waters, Lees would never arrive at Le Mans convinced that he could win.

“Toyota’s old turbo four had a lot of power but only for the short time before it twisted the block,” he says. “The V8 used too much fuel and we had to run slowly, plus we had gearbox problems all the time. It was the same with the [V10] TS010 [of 1992]: useless gearbox. They could easily have put Hewland parts in it, but TRD [Toyota Racing Development] wanted its name on everything. And you couldn’t trust them to do anything except the engine.

“The first time I drove a TS010 it was soft like a bloody rally car. But it came good and its chassis was better than the Peugeot’s. We won the first round at Monza, a little luckily, and we should have won at Silverstone but the electrical pick-up on the flywheel went wrong.

“It was my job to turn my co-driver Hitoshi Ogawa into a GP driver for Toyota. When he said to me that he was returning to Japan to do an F3000 race at Suzuka, I asked him why and told him he was better than that now. I was on holiday on the Virgin Islands when I heard that he’d been killed. We were really close.”

Lean fell-runner fitness would see Lees through the rest of the 1990s, his vow being to win Le Mans before retiring. His best chance of achieving that came in 1998 via the Team Toyota Europe-run GT-One.

“It was a good car, though its large turbo on a small engine made it difficult if you were slowed by traffic,” he says. “I didn’t reckon we’d finish, to be honest, but I got out after my last stint thinking that we were going to win and showered and put on a fresh race suit ready for the rostrum. When I emerged 15 minutes later a mechanic was crying. The transmission had seized. I’d done my job to the best of my ability and not made a single mistake, so I’d ‘won’ that Le Mans as far as I was concerned.”

Leading Le Mans in ’98 with 80min to go, Lees passed over his Toyota GT-One and departed to freshen up for his podium appearance… but it never came

His commitment to the cause took its toll: worsening lower back pain – partial legacy of that preference for stiff set-ups – caused his retirement in 2000. Ayako sadly died in 2010 and Lees returned to the UK two years later, initially in Sutton Coldfield before settling near Northampton. “I will go to my grave disappointed with my F1 career, but I am proud of my 33 years of racing.”

Many of which were spent as the world’s busiest racer. A professional’s professional.