Alastair Caldwell: The Motor Sport Interview

The shades-wearing former team manager at McLaren recalls his early days with Bruce, James Hunt’s world title fight and why the 1968 Belgian Grand Prix holds a special place in his heart

Revs Institute

Alastair Caldwell’s life in motor racing began in early 1967, stepping off the plane from New Zealand and onto the first rung of the ladder as a fabricator for Bruce McLaren at Colnbrook. By Monza in the autumn he was Bruce’s mechanic on the Formula 1 car. Three years later the team would be ripped apart when Bruce was killed testing his Can-Am car at Goodwood. Caldwell stepped up alongside Teddy Mayer, holding the team together, keeping the Kiwi badge on the grid as the founder would have wanted.

Alastair Caldwell tinkering with the BRM V12 of Bruce McLaren’s M5A at Monza, 1967.

Getty Images

Alastair Caldwell with Denny Hulme at the 1971 F1 non-championship Questor GP

Grand Prix Photo

As team manager he presided over two world championship wins, for Emerson Fittipaldi in 1974 and James Hunt in 1976. Then came Brabham, working with Gordon Murray and Nelson Piquet until ’81, when the Brazilian won his first world title. Midway through that year he went to ATS, but not for long, as he was already thinking about leaving the pitlane. Caldwell departed to start what is now a successful self-storage firm. He talks to Motor Sport about life at the pinnacle of the sport.

Motor Sport: What was your first impression of Bruce McLaren when you came to the UK?

AC: “I didn’t meet Bruce until my second day there. I’d started as a cleaner, became a fabricator and then a mechanic on the cars. He was immediately very friendly, nice to me, and asked me about the trip from New Zealand. I came by plane because, if you do that journey by ship, you’re off work for six weeks. Bruce was a natural leader. He never criticised people, he led by praise and positive encouragement, so if there was no praise you knew you hadn’t done a good job.

“He was full of enthusiasm. He’d climb into an unfinished car, just sheets of aluminium on a jig, make engine noises and pretend to drive it. ‘I can tell this is going to be a quick car,’ he’d say. We all loved that about him. He joined in with everything – typical Kiwi. He’d cut some aluminium, he’d turn up at midnight to encourage us, try to help. Before Monza in ’67 we were working late on the V12 BRM-engined car and he turned up, went out and got us some oil to fill the tank. He kept on pouring it in until we realised there was no bung in the tank. Bruce retreated with his smart shoes covered in oil. All good fun. He was a very cheerful, positive person and that always goes down well with everyone.”

Clockwise from left: Tyler Alexander, Teddy Mayer, Bruce McLaren, Denny Hulme, Zandvoort, 1968

Grand Prix Photo

Do the history books do justice to Bruce? Is he still underrated when it comes to the sport’s big figures?

AC: “He did a fantastic job. What he built up before 1970 was remarkable, and it was a team thing. We all did a good job for him. The whole McLaren ethos, the reliability, the engineering, the good-looking cars, the best trucks, smart uniforms and shoes, we had all that before Ron Dennis took over the team.

“Those of us with longer memories talk about ‘BR’ and ‘AR’, before Ron and after Ron. Remember, in the ’70s we won two F1 world championships, not to mention winning in America with our Can-Am and USAC teams. Maybe the Kiwis, and the Australians like Jack Brabham, didn’t really fit in with the British Establishment who were more in awe of Jim Clark, Graham Hill and Colin Chapman, all those guys. So yeah, Bruce is right up there whatever people say.”

Both your brother, Bill, and Bruce were killed in racing cars when you were still a young man. Were you ever tempted to walk away from it all?

AC: “Yes, very much so. I was tempted but I’d come from New Zealand, made a financial commitment to a house, moved my family, all that. If I hadn’t had those commitments I would have stopped and gone home. When Bruce was killed at Goodwood, Tyler Alexander and I went to work the next morning. We couldn’t just walk away from it.

“Bruce McLaren joined in with everything – typical Kiwi“

“I had doubts. I didn’t tell anyone else in the team. I was distressed and decided from that day on I would not befriend a racing driver, and I told them. Nelson Piquet wanted me to go on holiday with him to Brazil, James Hunt wanted me to party with him in Malaga. I refused them both. I told them I wanted to be at their funerals as their team manager, not their best friend. I’m just relieved and pleased nobody got killed in a McLaren on my watch in Formula 1.”

Teddy Mayer took over the team after Bruce died in 1970. How was that? You were two very different people

AC: “We got on fine. At work. It was a sea change. Teddy and Tyler [Alexander] were doing well in America, Can-Am and USAC, so their focus was on that while the Formula 1 wasn’t so important to them. When they came back from the States we had a successful grand prix team and they wanted to run that. I went upstairs to an office, Teddy tried my job on the shopfloor and it didn’t work. We weren’t as competitive, and I quit. I’m best in my boots and jeans, running a team, not sitting in an office in a jacket and tie.”

Caldwell in spring sunshine at Jarama for the 1972 Spanish GP sitting in Hulme’s McLaren. Gearbox problems would end Denny’s race at the halfway point

Getty Images

In ’74 you won the world championship with Fittipaldi, who left suddenly at the end of the following year. So now the team didn’t have a number one driver.

AC: “Yes, it was a big surprise to us too. Emerson wanted to do his Copersucar team in Brazil, and I think he threw away the chance of being champion again with us. He tried to get me to go with him but I said I’d only do that if the car was built in England. I felt they couldn’t make it work from Brazil.

“We had to move fast, the music had stopped and James Hunt was our only option. He rang me up and said, ‘Hello, I think I’m your new driver,’ to which I replied, ‘Yeah, I guess you are. This could be really good. You’d better talk to Teddy about the money. It won’t be much.’ We knew about James of course. He’d won races, he’d stopped crashing, wasn’t ‘Hunt the Shunt’ any more.

“So we went testing where we discovered his long legs didn’t fit in the car unless we moved the pedals and cut the toes off his shoes. First race, he’s on pole, and would have won it if a trumpet hadn’t fallen off the engine and jammed the throttle open but he kept on driving it, with the oil cooler falling off. Teddy got very upset, but I told him we wanted a racing driver who didn’t just stop the moment there’s a problem. So yeah, James was a great result for us.”

With Mayer, centre, and James Hunt at the 1977 Monaco Grand Prix, but Caldwell refused to become friends with F1 drivers

Getty Images

Ferrari’s Clay Regazzoni (No2) and Niki Lauda (No1) make contact at Turn 1 of the controversial 1976 British GP and James Hunt is unable to avoid a collision. Weeks of recriminations would follow

Getty Images

Like all world champions Hunt had a good car in ’76, with you and Gordon Coppuck improving the McLaren M23.

AC: “We introduced the six-speed gearbox, the air starter which saved weight, and early ground effects with the skirts on the M23. Gordon reckoned that gave us 300lb of downforce and no discernible extra drag. There were ups and downs. In Spain the car was too wide because of the new Goodyear tyres. That was my fault. I didn’t measure the car because I knew it hadn’t been changed, but I hadn’t realised the new tyres stuck out over the wheel rims. So we moved the oil coolers from the sidepods to the back of the car behind the wing and when we won the French Grand Prix we’d proved the ‘narrow’ car was as quick as the ‘wide’ car and we got the points back we’d been docked in Spain. That proved crucial for the battle with Niki and Ferrari.

“There was also the fiasco at the British Grand Prix at Brands in the summer. James was the only driver who did that race right by the rules. He stopped when the red flag came out, he took the re-start in his race car which we’d repaired. He was disqualified because he didn’t complete that first lap but we had followed the rules – stop when you see the red flag. He won that race but Ferrari’s politics were stronger than ours. They convinced the FIA and we lost the points. So yes, ’76 had its dramas, but we put it right at Fuji, Niki pulled out, James stayed out. We won the championship by a single point.”

In ’78 you went to Brabham which, I guess, was a very different place from McLaren?

Bernie Ecclestone with instructions for Nelson Piquet, 1981 Argentine GP; Caldwell is standing

Grand Prix Photo

AC: “I’d left McLaren because it wasn’t working out with Teddy Mayer, but I wasn’t at all sure I could work with Bernie Ecclestone either. I decided to give it a go despite my misgivings. There were even less people than we had at McLaren but there was Gordon Murray who I thought was a genius, Herbie Blash who was Bernie’s right-hand man, and Charlie Whiting, the chief mechanic, all good people. It was not a benign atmosphere, no free coffee and soup machines like we had at McLaren, and Bernie was always turning the lights off. He was an eccentric, a man who shot from the hip. I told him, ‘If you start shouting at me, I’m out of here.’

“Then there was Nelson Piquet. I really liked Nelson, a very nice young man, and a hard worker. He came to the factory every day. He was one of the very best, a natural talent, totally motivated to succeed, always willing to go testing, and he had a very good relationship with Gordon. Those Brabhams were always very quick. Gordon was constantly looking for those clever extra tenths. He and Bernie were keen on any technical advantage but what they needed was reliability and I worked hard on that. To win more races we had to finish more races.

“Bernie would turn up and make decisions over my head“

“In the end I couldn’t work with Bernie. He’d turn up at random, make decisions about the way we worked over my head, usually to save money. I reckoned I knew how to run a race team so I fought against what I thought were crazy decisions. We’d given it a go but it all came to a head halfway through the ’81 season and I quit – I got in my car and went home.”

The winner takes it all, although the highest finish for Swede Slim Borgudd with the ABBA-sponsored ATS in 1981 was sixth, here at Silverstone

You went to ATS, owned by another unusual individual, but didn’t stay long.

AC: “It wasn’t all bad. Günther Schmid was OK. He was an intelligent guy, seemed fairly sensible, though he didn’t put enough money into the team. We had Jan Lammers and Slim Borgudd – a Swede who put ABBA stickers on the car.

“A high point was my first race with them in ’81, the British Grand Prix, where we won a championship point for the team, Borgudd coming in sixth. That single point, the only one that season, made a huge financial difference to ATS. Schmid was delighted but he never bothered to thank us. If he’d spent less money on himself, and more on the team, and the cars had been competitive, it might have worked out better.

“I don’t think Schmid was really interested in the racing. He wasn’t around that much, and in the end I thought, ‘Why am I doing this?’ I’d gone to ATS, having left Brabham because I needed a job, but I was already beginning to think about life after Formula 1. John Hogan from Philip Morris had been saying I should start my own F3 team. I think Marlboro would have backed me, but that meant working my way back up to F1, and I didn’t need what I knew that would entail. So many race teams spend time begging for money. F1 teams have whole ‘begging departments’ to find new sponsors, year after year. I’d made a list of things I could do and ended up starting Space Station, my self-storage company which I’ve now sold.

“Formula 1 has lost some of its thrill but the cars are so much safer“

“I’d seen the way it worked while racing in America. We’d be between races or tests, F1 or Can-Am, and we’d need storage for the cars or the equipment. Nobody had started self-storage in England. It took me almost a year to get the first customer. It was hard work but I just thought, you know, I should create some wealth rather than keep working for motor racing’s eccentric millionaires.”

McLaren in a McLaren: Bruce on his way to a first world championship GP victory in a car bearing his name – Spa, 1968

Getty Images

How much interest do you take in Formula 1 today? The sport has changed dramatically since you retired.

AC: “I’m interested. I watch some of the grands prix. I think the actual racing has improved, the cars are running closer together, but it seems they can only overtake each other using the drag reduction system, which seems a bit farcical to me.

“The car has become increasingly more important than the driver. Of course that’s long been the case in Formula 1, but now I think a driver can make even less of a difference. A classic example was George Russell in Bahrain [in 2020]. He should have won the race but in a Williams he was struggling to get out of Q3. If you’d put Lewis Hamilton in that Williams even he couldn’t have overcome the car and so today it’s all about the car.

“Then there’s the money, and drivers buying their place in the team, but again that’s not exactly a new development. Yes, Formula 1 has lost some its edge and its thrill but the cars are so much safer, which is a good thing. Too many people were killed in the past. Netflix and social media have brought a new and different crowd to grand prix racing and that explains its current popularity.

“I was thinking, James would have loved all the girls who come to watch the races now, but then he was never exactly short of them anyway.”

What would be your best, most satisfying moment of your career?

AC: “That’s a tough one. I’d have to say winning the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa in 1968 with Bruce in the new McLaren M7A with the Cosworth engine. It was the only grand prix he ever won in his own car, McLaren in a McLaren, and the first one the team ever won. It was interesting because Bruce had brought some fancy new driveshafts that weekend, insisted we run them, but Allan McCall, who looked after Denny Hulme’s car, found some burring on them, a little hot spot, the night before the race. I didn’t like the look of this so during the night I put the old Hardy Spicer driveshafts back on Bruce’s car.

Hulme’s bright orange McLaren in the middle of the grid at the start of the 1968 Belgian GP

Grand Prix Photo

“On race morning Bruce hobbled into the garage and instantly asked me why I’d taken off the new driveshafts. I told him what I’d seen, that I wasn’t confident they’d go the distance. He spoke to Allan, came back, and said, ‘Little Al says the new ones will be fine.’ Bruce then ordered me to use the new ones but I refused. The guys were astounded that I’d stood up to Bruce. We’d always done everything by mutual agreement between us. He wasn’t happy, stomping off.

“Then come the race Denny retired from second place after 18 laps. A driveshaft had failed. Bruce was running fourth, or fifth, but people were dropping out ahead of him. Seeing him come through the field, I was changing the pitboard, P3, P2 and then P1 as he crossed the line. After the race Bruce asked me, ‘What happened to Denny?’ I said, ‘Driveshaft,’ and it was never spoken about again. It was a great day for New Zealand, a great day for McLaren. We were all so excited.

That’s a highlight if, or when, I’m looking back over life in grand prix racing.

McLaren, right, with Pedro Rodriguez on the podium, Spa, ’68

Getty Images

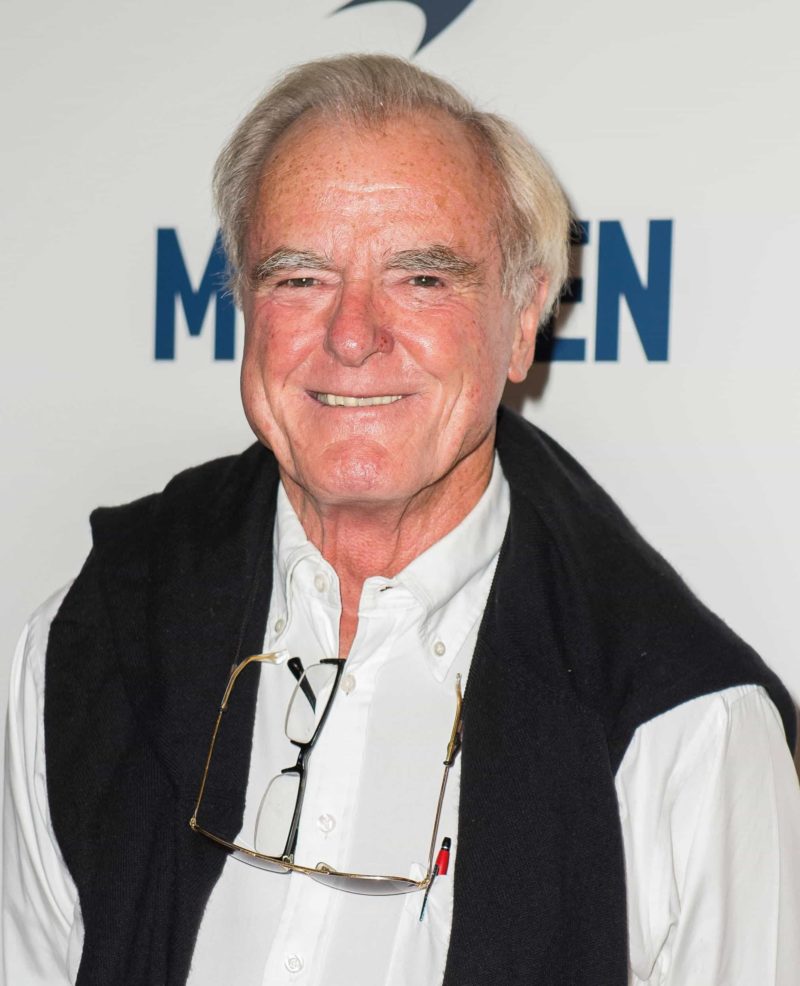

Caldwell at the screening of 2017 documentary film McLaren

Alamy