Bella machina: final bow for Campion Martini Lancias

A world-renowned group of Martini Lancias brought together by one man as a labour of love is up for sale. The cars will then likely disappear from public view, but not before James Mills gets an exclusive final look at the Campion Collection

Tom Gidden

The road to Amelia Island is a calm, gentle drive, tracing the Florida coastline and rolling past pretty wooden beachside properties. Pelicans perch motionless atop pontoon posts, the water is calm, and 99.9 Gator Country is playing. The calm doesn’t last.

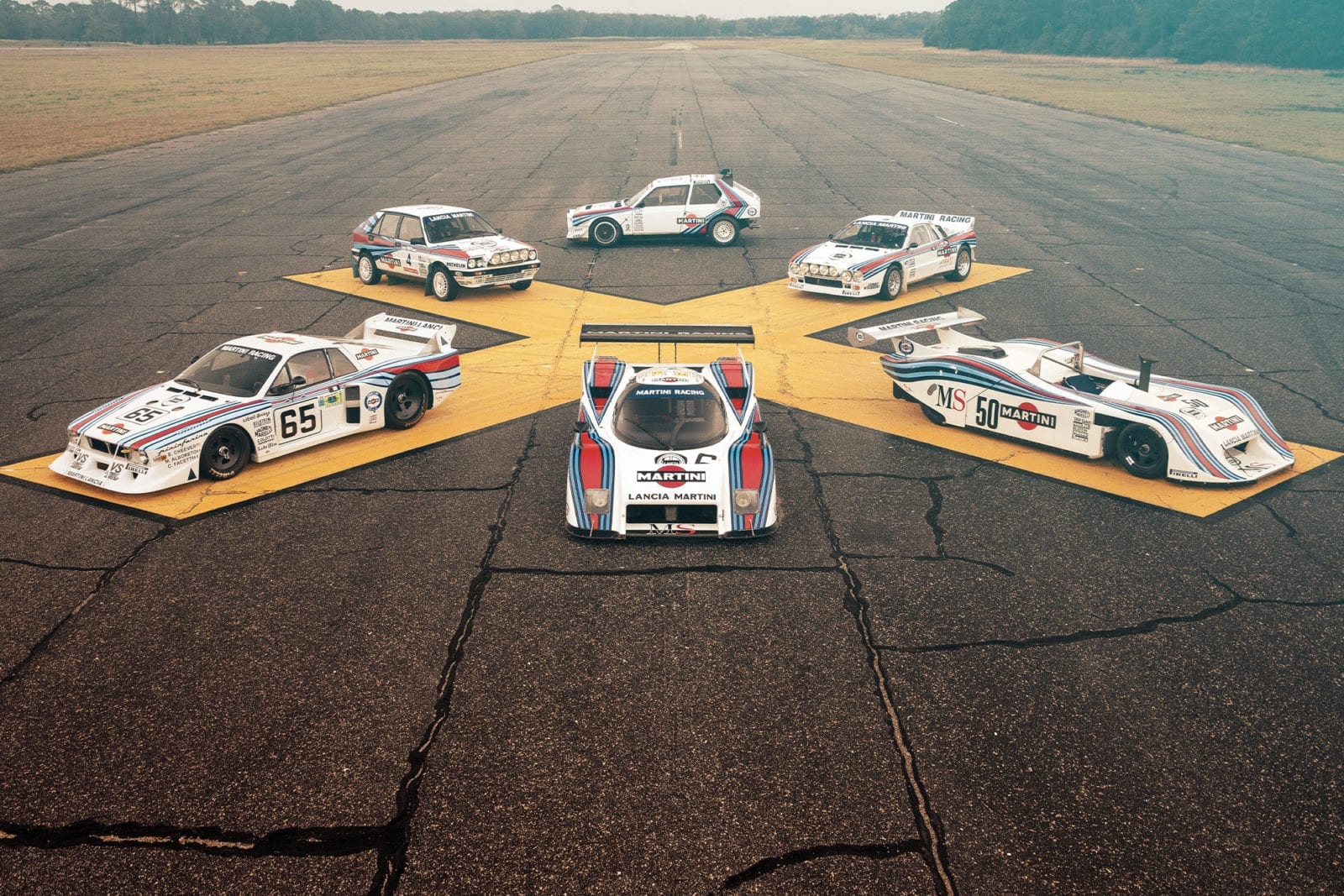

Waiting on a disused runway at Fernandina Municipal Airport are six of the wildest race and rally machines ever to roll out of Lancia. Some, such as the Delta S4, are infamous for being fire-spitting animals that pushed even the most talented drivers to, and tragically beyond, their limits. Others, notably the LC2, displayed dazzling speed and promise that would go unfulfilled.

They are cars from a time when Lancia provided motor sport fans with the sights, sounds and smells that remained embedded in their memories long after the Italian car maker as good as disappeared. Seeing them together serves up a snapshot of Lancia’s success in rallying and motor racing during the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s. Yet it also paints a picture of a company that found itself pushed around by parent Fiat, leaving key figures like Cesare Fiorio, the brand’s motor sport master, to skilfully steer Lancia around obstacles and uphold its reputation.

This is the last time anyone outside of the Campion Collection will see the six Lancias together. It’s a final farewell, after John Campion, the entrepreneur and motor sport fan who owns the world-renowned collection, put them up all for sale to focus on helping rising stars through his new CJJ Motorsports squad. The collection is being sold by Girardo & Co and we have been invited to witness the last hurrah.

Three of the Lancias have already found new custodians. Little surprise. The cars have been maintained regardless of cost, come inspected and authenticated by Lancia Classiche and boast comprehensive history files. Here are their stories, accompanied by insight from Riccardo Patrese and Miki Biasion, the drivers that raced and rallied them to victory.

Group 5: 1980 Lancia Beta Montecarlo Turbo

A two-time overall WSC champion, the Montecarlo defeated Porsche in 1980

Tom Gidden

Montecarlo had road car roots, unlike Stratos

Tom Gidden

The Beta Montecarlo Turbo is one of Lancia’s greatest successes in motor racing, boasting two overall World Sportscar Championships. Yet during the infancy of the project, few saw potential in the mid- engined road car. No matter. The person that counted most, Cesare Fiorio, knew it had the makings of a winner.

Far-sighted Fiorio was Lancia’s hugely successful motor sport manager and would go on to lead the resurgence of Ferrari in Formula 1 during 1989-91. After the success of the Stratos, which won three World Rally Championships in 1974-76, Fiat’s top brass, doubtless miffed, decreed that Fiat and Abarth should lead the group’s rallying activities with the Abarth 131.

Fiorio deftly steered Lancia into motor racing and knew the chosen car should be based on a showroom model, rather than a homologation special like the Stratos, to smooth approval from the powers that be.

“Early on in the project, few saw motor sport potential in the Montecarlo”

Senior engineer Gianni Tonti and chassis designer Giampaolo Dallara worked with Fiorio to manipulate the Beta Montecarlo within the Group 5 regulations. By the end of 1978, the mid-engined, 1.4-litre turbocharged Montecarlo, weighing 300kg less than the road car, was ready for the 2-litre class.

Riccardo Patrese was approached to drive for Lancia’s works operation. “At the end of the ’70s [1978] I drove the Fiat Ritmo Group 2 on the Giro d’Italia automobilistico, and that’s where my relationship with Cesare Fiorio began.

“Fiorio was very clever, always trying to get the best advantage he could from the regulations, pushing for the rules to suit his cars, always thinking ahead and having ideas that the others didn’t have. And he created a very happy working atmosphere, which is something he took to Ferrari. He knew that the force of the team was a nice atmosphere, motivation, working together. We knew we had a good leader who could work around the politics.”

Patrese was heavily involved in the development of the Group 5 Beta Montecarlo Turbo. “I did the first laps of the car with the chief engineer, Mr Gianni Tonti, starting with the volumetric supercharged engine from the 037. Then the turbo engine arrived, at the beginning of 1979, as we kept on developing the 1.4.”

The first race was the Silverstone 6 Hours, Patrese partnering with Walter Röhrl. The pair retired, but the half-season yielded one win, enough to suggest things were on the right track.

In 1980, Lancia threw its weight behind the World Championship for Makes and beat Porsche to the title, Patrese taking multiple wins.

He remembers the Beta Montecarlo for its agility and good handling – “Dallara did a good job on the chassis” – but says it was important to drive around the lag of the early era turbocharger. “You needed to brake and then put the power down much earlier than a naturally aspirated engine. But it was the same problem with the BMW engines in Formula 1.”

This car, chassis 1009, gave Campion the bug for endurance racing cars, and it was the first example he bought. Under Campion’s custodianship, 1009 has undergone a mechanical restoration, which included an engine and gearbox rebuild by Savannah Race Engineering.

Its wedge-like, Pininfarina-designed bodywork is so of the period that you half-expect the guys at Campion’s CJJ Motorsport operation to step out of their race car transporter wearing cowboy boots and flares, shirt open, perm in place and Marlboro red hanging from the lips.

The stylish Campagnolo wheels are unquestionably some of the coolest ever to grace a race car. Inside, it’s a shock to find how the design of the front-end gave little thought toward the positioning of the steering column and pedals. They are set far over to the left, so much so that the seat is angled slightly in an attempt to help the driver remain comfortable. A personal claret-red suede wheel, engraved with ‘R Patrese’, stares back at you, and the cabin feels rather rudimentary. But who cares when you had all the right ingredients beneath you?

Light, fast and reliable, the Beta Montecarlo Turbo showed that Lancia still had what it took to win on the track, as well as on a rally stage.

1980 Lancia Beta Montecarlo Turbo

Engine: 1.4 turbocharged straight-four

Power: 460bhp estimated

Weight: 780kg

0-60mph: 3.6sec estimated

Top speed: 178mph

Group 6: 1982 Lancia LC1

The LC1 was Lancia’s first bid at ground- effects, but was caught out by the FIA and WSC

Tom Gidden

Driver protection was at a minimum

Tom Gidden

Sat in the driver’s seat of the LC1, it’s easy to see why Campion couldn’t resist adding his final Lancia to the collection in late 2016. It’s a racing machine born of simpler times. You sit low, the view ahead is unimpeded, bar the rear-view mirror on its stilt, and there is precious little to the cockpit or the car’s safety hardware.

It’s also rare. Just four LC1s were built as the company looked to move up the ladder in the World Endurance Championship. But Lancia found itself wrong-footed by the FIA, which wished to phase out Group 6 and attract manufacturers to the newly formed Group C class. Group 6 racers would no longer be eligible for the manufacturers’ championship, but the drivers’ title was still up for grabs. The fuel economy restrictions didn’t apply to little old Lancia, so it was able to fight it out with more sophisticated and powerful Group C rivals.

“This LC1 took the overall win at the daunting Nürburgring 1000Kms”

There was much to admire about the LC1. It was the first car to take Lancia into the murky, emerging world of ground- effects, with more than 120 hours of wind tunnel work conducted at Centro Ricerche Fiat, in Orbassano, on the outskirts of Turin. The Kevlar and carbon bodywork weighed just 58kg, while the Dallara aluminium monocoque, built around magnesium-alloy ribs, tipped the scales at 55kg, which is why the LC1 was so light at just 640kg.

Another reason for its featherweight status could be found behind the driver’s back. Abarth built on the four-cylinder engine found in the Beta Montecarlo Turbo, and it had a considerable weight advantage over the flat-six of its Porsche 956 adversary. All of which meant it was seriously quick. LC1s took three pole positions and three victories during the 1982 season.

This very car qualified second on three occasions and took the overall win at the daunting Nürburgring 1000Kms, with Michele Alboreto, Teo Fabi and Riccardo Patrese sharing the driving.

Did the exposed cockpit ever play on Patrese’s mind? “I drove the LC1 last year, and it made me realise how little protection you had for a very high-speed car! In fact, I had a very bad accident [in 1982], at the Nürburgring, when the car turned over in qualifying, and the roll bar collapsed, so my helmet scraped along the floor, and I was unconscious.

“I remember waking and hearing Michele [Alboreto] pushing the marshals to turn over the car and get me out.” Clearly, it didn’t affect Patrese too much, as he won the 1000Kms the next day.

The Group 6 machine was short-lived but successful, delivering Lancia the World Championship for Makes in 1981 and keeping Patrese in contention for the 1982 drivers’ title into the final round. At Brands Hatch, Jacky Ickx won by a handful of seconds and finished ahead on aggregate standings, after Patrese’s co-driver Fabi lost ground following a race restart, which meant the race finished in the dark and Fabi lost time lapping cars because the LC1 had no headlights.

Opening the front and rear clamshells reveals acres of space for spanners and elbows. The bodywork looks to be perched on nothing more substantial than beanpoles, yet this is a car that tore along the Mulsanne and Döttinger Hoe straights at over 200mph.

The Lancia has a wonderful patina, with every battle scar visible. I wonder what it’s worth, relative to the LC2 and a contemporary works Porsche. I’m told it’s probably in the region of £1.3m for the LC1, versus £2.5m for the less successful LC2. By contrast, a Le Mans-winning Rothmans 956 sold at auction for around £8.3m in 2015. By all accounts, the Le Mans Classic-eligible LC1 is a bit of a steal.

Opening the car up reveals the LC1 was easy to work on, yet looked somewhat fragile

Tom Gidden

1982 Lancia LC1

Engine: 1.4 turbocharged straight-four

Power: 480bhp

Weight: 640kg

0-60mph: 3sec estimated

Top speed: 205mph

Group C: 1983 Lancia LC2

This example launched the LC2 to the world in Turin in early ’83, alongside the famous 037 too

Tom Gidden

If ever there was a racing car that screamed untapped potential as loudly as its engine roared down the Mulsanne Straight at more than 200mph, it was Lancia’s LC2.

Conceived to allow Lancia to take on Porsche, the masters of sports car racing, the LC2 was breathtakingly fast but frustratingly temperamental. Ultimately, and much to the disappointment of Group C racing fans, its life would be brief and its potential never fulfilled.

Yet how it pulled at our heartstrings. Here was a Lancia that was powered by a Ferrari engine, rekindling memories of the Stratos and its Dino V6, or even the earlier 1950s Lancia D50 V8 grand prix car that would morph into a Ferrari, once the Lancia family sold its shareholding of the company.

Initially, Ferrari created a 3-litre V8 and injected some Formula 1 magic, with ingredients such as two KKK turbochargers, BEHR intercoolers and Weber-Marelli electronics that could be found on the Scuderia’s 126C. Around this, Abarth and Dallara created an aluminium monocoque with honeycomb reinforcement, a titanium roll bar and carbon-Kevlar- composite bodywork.

Only seven were made, with two reproductions following after. This car, chassis 0001, made its debut at the Lancia Martini Racing press conference in Turin in early 1983, alongside the Rally 037 and the F1 Powerboat, with Alboreto and Walter Röhrl posing for pictures and fielding questions. Alboreto had plenty of Lancia experience to his name; the squad also called upon the services of Alessandro Nannini, Mauro Baldi, Riccardo Patrese, Bob Wollek, Teo Fabi, Hans Heyer and even Henri Pescarolo.

“It was a pleasure to drive that car,” recalls Patrese, “especially for a Formula 1 driver. I came from F1 when, aerodynamically, it was getting better. When I swapped to the Group C car, it was easier because the aerodynamics were working very well. It was really like driving a Formula 1 car, and in fact, the lap times were very close.

“I was much busier with Formula 1, which had become more time consuming, during the Group C car’s years and was not involved in the development of the car, whereas I was really with the project a lot with the Group 5 and Group 6 cars. I think the car had great potential but because they wanted to be more involved in rallying, they stopped the programme. It was a shame.”

“Some suggest the LC2 needed an evolution to achieve its true potential”

The car’s five-speed gearbox was unreliable, and the team’s brightest brains and greatest resource were tied up in rallying. There were also tyre issues after Pirelli withdrew from sports car racing, forcing Lancia to switch to Dunlops of an entirely different construction. Bad luck also appeared to plague the programme.

Pole positions were easy to come by. The LC2s reputedly hit well over 200mph along the Mulsanne at Le Mans. This car was entered for the 1983 race, but a fuelling miscalculation halted it, writing off its flying lap and dropping it to 13th, before retiring.

Campion and co then treated the LC2 to a complete mechanical rebuild but wisely opted to preserve the car’s originality. It has been used for track days, to get a feel for the car and to keep all the parts moving and was driven to 170mph during an exhibition ahead of the Daytona 24 Hours.

Those with experience of the Group C racer suggest it needed an evolution, an LC3 perhaps, to achieve its potential. But the reality was that Lancia was forced to focus its resources on rallying, and preparing for Group A for 1987, after the FIA banned Group B. It would take TWR and Jaguar, and Sauber and Mercedes, to pick up from where Lancia left off and end the dominance of Porsche.

1983 Lancia LC2

Engine: 3-litre Ferrari V8

Power: 800bhp estimated

Weight: 850kg

0-60mph: 3sec estimated

Top speed: 223mph

Group B: 1983 Lancia 037 Rally Evo 2

Tom Gidden

The 037’s place in motor sport history is well and truly cemented as the last two- wheel-drive car to win the World Rally Championship for manufacturers in 1983, beating the four-wheel-drive Audi Quattro. But it took blood, sweat and tears to get there.

The previous year, the 037 had been plagued by poor reliability. A former Fiat works driver recruited by Lancia, Attilio Bettega, broke both his legs after his 037 hit a wall during the Tour de Corse, and he was sidelined for the rest of the season.

“Limone shudders at the state of customer Stradales”

When the Lancia hit its stride, the competition couldn’t believe what they were seeing, particularly Audi. According to Sergio Limone, the project manager for the 037, Walter Röhrl’s co-driver Christian Geistdörfer wickedly fed rumours back to Audi that there was a secret four-wheel-drive system. The Germans dispatched a man in a helicopter to track the Lancia, so it could land when the car stopped, and Audi could steal a look underneath to see if the rumours were true. Depressingly, they weren’t.

Its performance would justify Limone’s proposal to keep things simple, given how little preparation time the team had. Even at the start of the project, it was unknown which manufacturer – either Abarth, Fiat or Lancia – would spearhead the rally programme.

Limone argued the Montecarlo’s chassis should be modified. But the proven twin-cam, four-cylinder engine that had powered the Fiat 131 Abarth to three World Rally Championships, and resided in the 124 before that, was paired with a Roots supercharger. This was done upon the insistence of Fiat’s engine man Aurelio Lampredi.

To adhere to the new Group B regulations, 200 cars had to be built. To this day, Limone shudders at the state of the customer Stradale versions, which all had to be worked on before they could be handed over to their owners.

Miki Biasion switched from Opel’s Ascona 400 to the 037 and discovered why his main rival on the Italian rally scene, Antonio Tognana, was so fast. Speaking with Motor Sport, he takes up the story. “I immediately got a very deep feeling with the car. It was like a racing car, but not easy to drive.

“You had to respect it. The secret to being fast was to be smooth with the throttle pedal. If you are very aggressive, you put all the weight on the rear wheels, and the front would understeer. So, it was better to arrive late with the engine braking and brakes and to do the first half of the corner as deceleration, then when the front reaches the right line to exit you could push on the throttle. It was a big challenge for me to put two-wheel drive on the podium against the four-wheel-drive cars.”

Biasion attributes its characteristics to the car’s specification, originally conceived for motor racing. While it seemed odd to develop a two-wheel-drive car for 1983, he says Lancia had its reasons. “The experience with the Lancia Stratos suggested that with a proper, well-balanced, two-wheel drive, central-engine car, they could be competitive. And in ’83, with Markku Alén and Walter Röhrl, Lancia won the World Championship against Audi.”

There were two evolutions of the 037, and only 20 Evo 2 versions were built. This 2.1-litre car is the 11th of the Evo 2 run, chassis 411, and was originally used by the works Lancia team and Alén. It was then driven by Dario Cerrato during his 1985 European Rally Championship- winning season.

It was the first car that Campion added to his Lancia collection, after purchasing a Stratos that gave John the Lancia bug. It’s the only car in the collection not to be rebuilt, but that simply adds to the car’s provenance.

The dashboard is simple and features digital displays for oil and air pressure, as well as water and oil temperature. A two-spoke suede wheel bearing the Abarth name, Sparco seat, and alloy pedals are perfectly placed for the driver. Meanwhile, the co-driver takes charge of a bank of fuses, timing gear and radio equipment. The doors and roof feel paper-thin, and on the passenger door sits the registration plate, W67780 T0. At the edge of the dashboard is an SOS number for the co-driver to call in the event of a crash or retirement. I resist the temptation to dial it.

It has a beast of a clutch pedal, heavy with a long-travel, and also a long-travel throttle. When its engine fires after several goes, it sounds like a two-stroke bike engine as it revs. The Lancia serves up 325bhp at 8000rpm on a good day. The cabin is very noisy and there’s a sense of being impossibly low to the road.

That noise grows more intense as the car corners flat, and you can feel the balance that comes from driving the rear wheels as it changes direction. The gearbox, however, is something of a stubborn so-and-so.

I’ll leave it to Alén, who named the 037 as his favourite rally car, to paint a true picture of the speed of Lancia’s creation. “The balance of the 037 was so good, especially on the jumps in Finland. There was no limit when jumping, and I was always confident to take very big risks. I remember once in the night, in Finland, thinking I was the best driver and decided to take many of the jumps flat out. The feeling with this car was so good that, afterwards, I had to change all my notes for braking to be 20 metres later.”

1983 Lancia 037 Rally Evo 2

Engine: 2.1 supercharged Fiat twin-cam

Power: 325bhp estimated

Weight: 960kg

0-60mph: 3.7sec estimated

Top speed: 140mph

Group B: 1985 Lancia Delta S4 Corsa

Tom Gidden

Tom Gidden

Even as it began work on the 037 in mid- 1980, Lancia knew that its car’s days were numbered. Four-wheel drive was the way forward for consistent performance on all surfaces and Lancia required a new approach.

The brainchild of Pier Paolo Messori, the ‘036’ concept had originally been sidelined in favour of the 037. Based on a Lancia Delta with a Ferrari engine, rear transaxle and a tubular chassis, it would ultimately be refined into the famous Delta S4.

On the S4’s competitive debut in the 1985 RAC Rally, Henri Toivonen took the victory, while Markku Alén took second. Toivonen was two minutes ahead of third-placed Tony Pond in his Metro 6R4, and 26 minutes ahead of Per Eklund’s Audi Quattro A2 in fourth. Not bad for what was meant to be a test ahead of 1986.

“The Delta S4 concept won the 1985 RAC Rally on its debut”

However, Miki Biasion, who was involved in the car’s development from the start, reveals that the car was initially something of a dog, and it took a massive effort to get to that level of driveability. “The 037 was faster than the S4 almost everywhere except the most slippery places. The first few months was frustrating. It was the first four-wheel-drive Lancia and drivers and engineers didn’t have the experience, especially with the differentials. It was a challenge to develop the car.

“We started with around 20 or 25 per cent front traction, and the car was very difficult to maintain its lines. You couldn’t feel any feedback through the steering wheel either. And it would react strangely because the front diff wouldn’t behave as you’d expect. We had to work and work, drive and drive, to get it to a point where it was relatively easy to drive.

“At least the engine’s torque and power were good. But the brakes weren’t good, and the suspension needed more work. I would say the engine was nine out of 10, whereas the suspension was six out of 10.”

Lancia got the car ready. But after a debut win on the 1985 RAC Rally and victory on the 1986 Monte Carlo Rally, development eased – just as Audi and Peugeot hit back…

The S4’s first-of-a-kind 1.7-litre, four- cylinder, supercharged and turbocharged engine is said to make around 550bhp at 8400rpm, and the red line is marked at 9000rpm. Modern data claims the 950kg S4 is capable of accelerating from standstill to 60mph in less than 2.5secs on a gravel surface. It’s amusing to note that the turbo boost gauge is set upside-down so that the driver can easily check whether he’s getting full pressure.

Of all the cars gathered here, the S4 looks the most outlandish. The rear clamshell bodywork appears to struggle to contain the engine and gearbox, while wide Pirelli P7 Corsa semi-slick tyres (315/40 R16) sit proud of the flared rear wheel arches. It’s as thug-like in appearance as the 037 is delicate. Hardly surprising as a mix of experimental parts, brought together in a display of brute force.

Yet the S4 feels remarkably friendly to drive. At least, it does at sane speeds. The clutch is light, the throttle wonderfully responsive, the slightly low-geared steering is feelsome, and the five-speed manual gearbox is more cooperative than even the later Delta Integrale’s. The four-wheel-drive system gave up to 75 per cent of drive to the rear and featured an active centre differential.

Yet those that know the car well, and have driven it harder, say there is a fine line between the S4 being on your side or against. Given the world’s greatest struggled to manage this monster, there is no reason to doubt them.

1985 Lancia Delta S4 Corsa

Engine: 1.7 turbocharged and supercharged four-cylinder

Power: 550bhp estimated

Weight: 950kg

0-60mph: 2.5sec estimated

Top speed: 150mph

Group A: 1988 Lancia Delta HF Integrale 8-valve

Tom Gidden

Tom Gidden

The cover of 1988’s April edition of Motor Sport featured an Integrale leaping through the air during Rally Portugal, above the headline ‘Biasion’s challenge takes off ’. Miki Biasion and fellow works drivers – Markku Alén and Mikael Ericsson – gave the original Integrale its debut in Portugal, using a five- speed gearbox rather than the planned six- speed unit that was running late. Biasion’s was the only gearbox to stay intact, and he put it to good use, earning the Integrale a debut win.

An evolution of the Delta HF 4WD, the Integrale brought important updates that allowed Lancia to flex its muscles in Group A. There was a more powerful tune for the transverse 2-litre, 8-valve, four-cylinder engine, thanks to the much larger Garrett T3 turbocharger, superior cooling, suspension enhancements and flared wheel arches, which permitted larger wheels, tyres and brakes.

Biasion’s win was no fluke. Lancia’s preceding HF Delta 4WD took Juha Kankkunen and Lancia to the drivers’ and manufacturers’ titles the year before. As it evolved, the Integrale clinched a further five manufacturers’ crowns and three drivers’ titles.

What was the Delta’s secret, a car that won six manufacturers’ titles and four drivers’ championships, a pair apiece for Kankkunen and Biasion? Not what you might imagine. Although every evolution brought better roadholding and weight distribution, it was the engineers that made the difference.

“During the evolution of the Delta, the engineers [from the rally team] told the production car engineers to standardise as many nuts as possible throughout the car, so that when they worked on the car during service, it would be easy and fast to change

parts like the gearbox, suspension, engine parts. Lancia made everything easy to work on, so you didn’t lose time during the rally.”

Campion’s car was driven to victory by Biasion on the 1988 Acropolis Rally, and Jorge Ricalde drove it when he beat Biasion at the Argentinian round that season. It was later shipped to Australia, where it was driven by Greg Carr in national and international events, and remained in its original, 8-valve spec.

The Group A regulations greatly suited the compact four-wheel-drive Delta and meant that this is the only car in the Campion collection that feels familiar and friendly.

I discover that the original dogleg, six- speed, straight-cut manual is stubborn and crunchy. The throttle is precise, but the turbo is asleep until 4000rpm, at which point the Integrale becomes urgent as it surges through the short-ratio gears to 7000rpm and builds speed rapidly. The distinctive crisp growl of the Lancia’s motor takes me back to my days testing the road car.

The steering is quick-acting and full of feedback, while the whole package feels taut, together and confidence-inspiring. In other words, it’s exactly what you’d expect from one of the most successful rally cars of all time.

1988 Lancia Delta HF Integrale 8-Valve

Engine: 2.0 turbocharged four-cylinder

Power: 275bhp

Weight: 1120kg

0-60mph: 6.2sec estimated

Top speed: 134mph