Why Porsche 917 terrified Attwood: ‘I knew it was going to be a problem the moment I saw it’

Le Mans winner Richard Attwood remembers the fearsome Porsche 917

Hans Herrmann and Richard Attwood celebrate their Le Mans 1970 win – one of three consecutive drives for Attwood here in the terrifying Porsche 917

Porsche AG

Richard Attwood strides into the pub, dapper as ever just days after his 85th birthday, and greets me with an enormous grin. The pub is significant, not for what, but where it is. When we were arranging our meeting he insisted on knowing the precise route I’d be taking from my home in the Wye Valley to his in the Midlands because he wanted to make sure it was as convenient for me as possible. If you know Richard, this will surprise you not in the very least.

Attwood today, now aged 85, with Andrew Frankel

There’s so much we could be talking about. There is his unexplained escape from death towards the start of his top-level career, when during the 1965 Belgian Grand Prix he wrapped his Lotus 25 around a telegraph pole at the exit of the Masta Kink leaving him unharmed but entirely unable to extricate himself from the now banana-shaped Lotus until, that is, the whole thing went up in flames. “So I got out of the car,” he says, still entirely unable to say where the superhuman forces required to do so came from, other than his mortally threatened instinct to survive. Or his one-off return to Le Mans in 1984, 13 years after retirement, to race an Aston Martin Nimrod with John Sheldon and Mike Salmon which ended in another fire, this time putting the former in hospital with serious burns.

But while today’s subject is indeed Le Mans, we’re going to keep it to just three of his nine participations, when he was racing for the Porsche factory between 1969-71. Even so, I’m a touch concerned about the premise for this story, because if Richard doesn’t agree with it, we’re in trouble. So I think we’d better get it out the way nice and early.

“Would it be fair to say you should have won two of those races but didn’t, and should not have won one, but did?” I ventured.

Attwood thinks for a moment during which time I convince myself he’s composing the words with which to let me down gently before he says, “Yes, I think that is absolutely fair to say.”

After a sigh of relief, I ask him how he even found himself as a works Porsche driver.

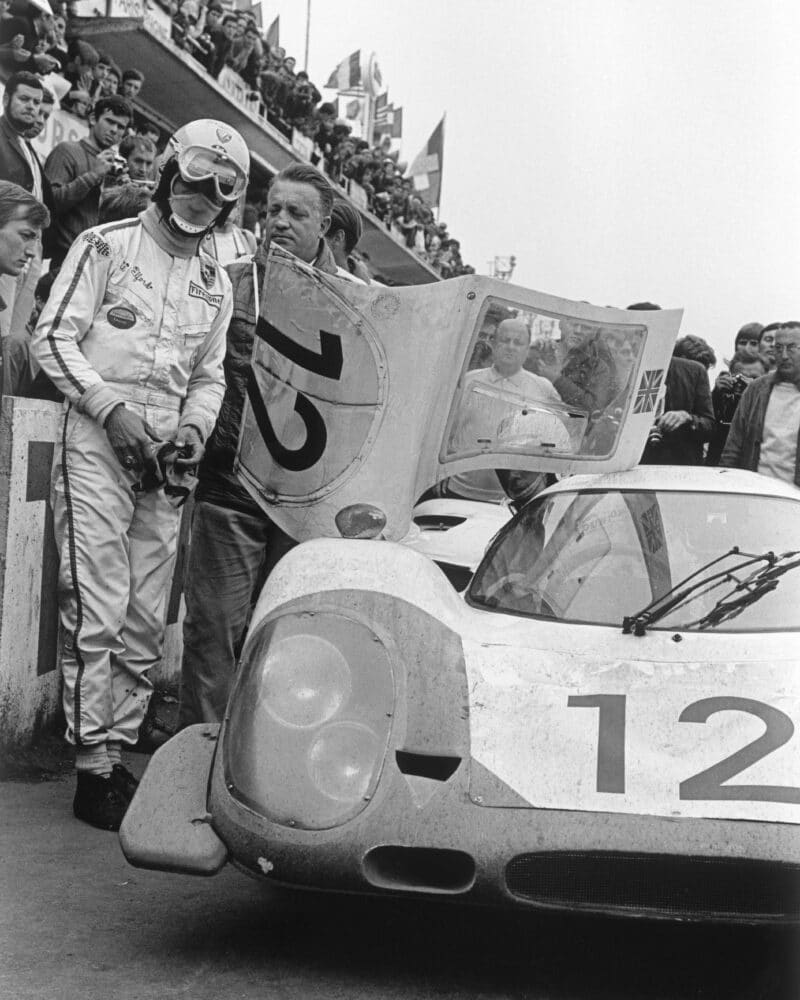

Porsche’s Attwood and Vic Elford were leading in the 1969 Le Mans 24 Hours until a gearbox issue in the 22nd hour

“It started when I was asked to do a race at Watkins Glen in 1968, in a 908, because Porsche wanted to be represented by drivers from around the world. I was originally meant to share with Tetsu Ikuzawa but it didn’t work out like that. But even though we retired, it must have gone quite well because I was then asked to do the 1969 season for Porsche.”

He nearly didn’t accept because John Wyer wanted him in a GT40, but he figured it was already an ageing car and Porsche was always pushing the limits. He did not at the time perhaps appreciate just how far those limits would be pushed by a handy device the factory was working on called the 917…

“I knew the car was going to be a problem the moment I saw it”

But with the 917 not yet ready, Richard started his 1969 season at Daytona in what turned out to be three different 908s as he was shuttled from car to car as, one by one, they all broke. Sebring was a little better as sharing with Vic Elford they at least finished, albeit down in seventh place, delayed by a leaking oil tank, but second at Brands Hatch was much more like it and at Monza they were third in a train of works 908s when a puncture sent Vic into the barriers and out of the race.

The 917 made its debut at Spa but even the absurdly brave Jo Siffert refused to race it, leaving the honour to Gerhard Mitter who lasted precisely one lap before the engine blew, possibly much to his relief.

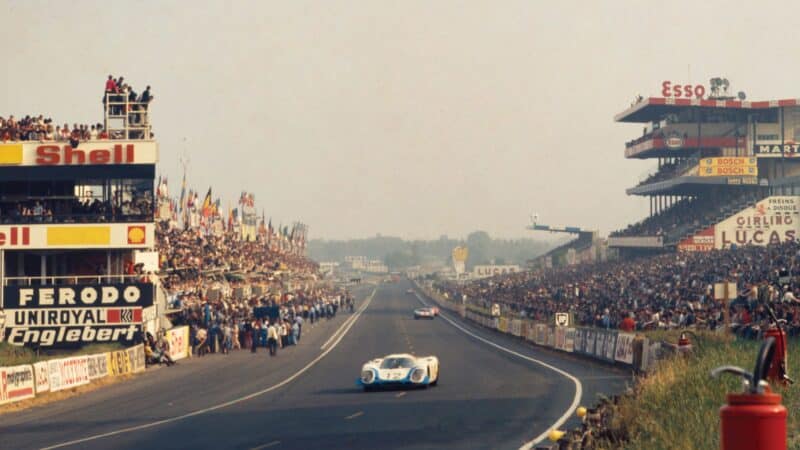

And so to Le Mans. Its stability problems still unresolved, despite its race-winning potential, the 917 was not exactly first choice among the factory drivers.

Elford, left, and Attwood, seated, at La Sarthe in 1969; afterwards a shattered Attwood felt glad to have survived his hours with the 917

“No one wanted to drive it. I thought it was probably my turn so accepted it when Porsche said I was to drive with Vic, and it was years later at Goodwood before Vic told me he’d asked if he could drive it with me. If I’d known I’d have backed out of it straight away. I only did it because it seemed to come straight from Porsche. I knew the car was going to be a problem the moment I saw it on a stand because it’s profile was almost identical to a long-tail 908, and that was absolutely on the limit of acceptable aerodynamic stability, and here was a car whose engine was half as large again. Flat out at Monza the 908 did 195mph. At Le Mans we were doing 235mph…

“I’d never driven anything like it, with that level of performance. The exhausts exited under my seat so I was deafened after two hours, my neck had gone and the bloody thing lasted for 21 hours. It was only meant to do six [that’s how long Porsche expected it would last]. An example. The Mulsanne kink was flat out. Not just flat, but easy flat. In anything. Not the 917. We were nowhere near flat in that. You had to ease off, get a bit of attitude on the car before you turned in, or else you get what happened to Digby.”

He’s referring to ace Chevron racer Digby Martland who was invited to share the first privateer 917, owned by John Woolfe. In practice he duly spun it at vast speed, somehow managed not to hit anything, drove slowly back to the pits and walked away not only from the car, but the race. He was replaced by the vastly experienced factory test driver Herbert Linge who begged Woolfe to let him take the start. Woolfe insisted on doing it himself and was killed before the first lap was completed. “Digby going home was one of the bravest decisions I ever saw a driver make,” Richard recalls.

Yet despite having to manage the car the entire time, it was so fast that with just two and a half hours to go it was four laps clear of the next quickest car when something in the transmission, the bellhousing or clutch, started to pack up. “You couldn’t get a gear so we had to call it a day.”

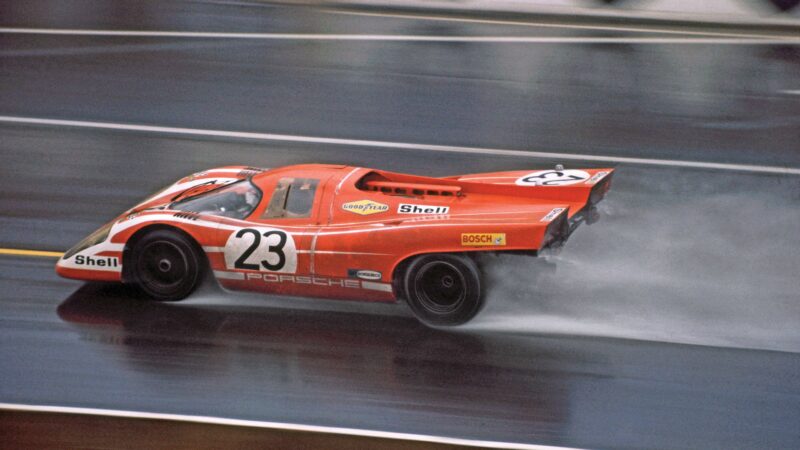

In atrocious conditions at Le Mans in 1970, Porsche reigned, winning all classes – including the overall race with this 917K, driven by Attwood and Herrmann

Getty Images

But far from feeling desolate at being so cruelly robbed of such a hard-fought result, Richard felt only relief.

“By that stage I couldn’t have cared less about the win. All I knew was that it had been a nightmare, and now it was over.”

What he couldn’t have known at the time is that failure at Le Mans actually sowed the seed for his (and Porsche’s first) victory the following year.

“They [the factory] knew I’d given everything I had to give in that race. When it was over, I was finished. Spent. Total mental and physical exhaustion. I must have looked like death. But they thought I looked that way because I was so disappointed not to win the race, when in fact I was delighted. So that’s why I was told I could choose both the car and my team-mate for the following year. I don’t know that they’d ever done that.”

“In a car like that you just don’t want to be out in the wet”

I wonder how many drivers of that era would have just said, “Put me in your fastest car and give me your fastest co-driver”? Probably most, but not Richard. With both 4.9-litre and 4.5-litre engine capacities available he chose the smaller motor. When the choice came to a four or five-speed transmission, he chose four. Offered short or long-tail bodywork, he chose short. And of all the drivers on Porsche’s books, he opted for the 42-year-old Hans Herrmann not because he was Porsche’s fastest driver – with the best will in the world he was in the twilight of his career and nowhere near the level of a Jo Siffert or Pedro Rodriguez – but because Richard reckoned he’d likely be the most reliable. “I thought it might be quite nice to actually finish the race.”

But these were decisions made in February when he still considered the 4.9-litre engine in particular far from proven. Come June he realised he’d made a horrible mistake.

“I remember saying to [his wife] Veronica, ‘We have not got a chance in this race.’ After qualifying there were 14 cars in front of us. Our best lap was a dozen seconds off pole. You cannot tell me that they’re all going to fail. One of them, probably more, will get through for sure. I thought I’d made the biggest error of my life. It was a disaster.”

Today we know that Porsche has won here at La Sarthe more than any other maker, but Attwood and Herrmann gave it its first win in 1970.

Getty Images

He didn’t even consider the appallingly wet conditions that characterised much of the race gave them an advantage.

“It was just an added complication. And in a car like that you just don’t want to be out in the wet, and it was really, really wet. Besides, I think we were already leading when the worst of it came, so I can’t say we were relying on it.”

The race turned into a war of attrition of a kind that has rarely, if ever, visited the race before or since. Of the 51 cars that set off on Saturday afternoon, just seven had completed sufficient distance 24 hours later to be classified as finishers. But at their head, five laps clear of the field, came the Attwood/Herrmann, Salzburg-liveried 917.

“I’d had a good run so 1971 was really about winding down”

“Honestly, I thought it was ridiculous. There were so many great drivers in cars far faster than ours. If any of them had just stroked it along, they’d have won easily. They could have gone fast when it was dry and just back right off when it was wet.” That said, Richard does admit to finding himself unexpectedly busy in the Esses, with the 917 at a distinctly unorthodox angle of attack. “Could have ended it right there and then,” he muses. Still I think over a largely wet day and night in a 917, he can be forgiven one slip.

But as if winning Le Mans in a Porsche 917 in the wet were not enough of an achievement, Attwood did the entire race on a diet of milk.

‘I knew I was unwell because I couldn’t swallow. At the victory dinner I couldn’t stay awake and had to leave after 20 minutes.” Though he didn’t know it at the time, he was then and will almost certainly always remain the only driver to win the Le Mans 24 Hours while suffering from mumps.

Attwood, Le Mans, ’70

Getty Images

By the end of the season Richard already knew the next would be his last. “The time was right. I’d lost so many friends, I got married and I had responsibilities towards the family business. I’d had a good run, so 1971 was really about winding down for me.”

A good run indeed. While his Formula 1 career had never quite taken off, there were moments of brilliance, none more so than at Monaco in 1968 where he’d been drafted in to the BRM team to replace Mike Spence who’d tragically lost his life earlier in the month at Indianapolis. Driving a car he’d never raced before, having done a grand total of one world championship race since the end of 1965 (a one-off drive in a Cooper-Maserati at the 1967 Canadian Grand Prix) and in only his second race in a 3-litre Formula 1 car, Richard came second to Monaco master Graham Hill (racking up his fourth win), by just over 2sec with the next fastest car four laps down. And broke the outright lap record in the process. He’d won Le Mans and never seriously been hurt in what was surely motor-racing’s most dangerous era.

Which is why Le Mans was the first of just three races he’d do for Porsche in his valedictory year. Now racing for John Wyer’s factory team, this time there was no choosing car or co-driver: it was the full fat 4.9-litre, five-speed 917, with highly evolved, finned short-tail bodywork and the Swiss driver Herbie Müller to hand over to. Müller had by then already done Le Mans seven times but to date had only seen the flag once, driving for Scuderia Filipinetti back in 1964. Then again, it was also the only time to date he’d driven a Porsche there…

“It was a last-minute thing with John Wyer, because I think he was only going to run his two long-tail cars, then decided to make a third entry. Herbie had a reputation for being a bit of a wild child, so I sat him down before the race and told him we had to be sensible, that we were the third car but you never know how things will work out at Le Mans. I gave him a proper lecture and actually he drove perfectly.

“It was Pedro’s race. I just minded the shop while he took a break”

“And we should have won that race too because we had the gearbox jam in a gear. So I brought it in and they went to work. We couldn’t change the gearbox so they had to completely strip it down, find out what was wrong and repair it. And of course it was all red hot. It took around 40 minutes. Then the winning car had the same problem, but by now they knew what to do. They did it in something like half the time. We lost the race by five minutes…” The next quickest car was 29 laps down. It was the fastest Le Mans in history by a distance, the winning Martini 917 of Gijs van Lennep and Helmut Marko averaging over 138mph for the duration and thanks to the 3-litre formula introduced in 1972 and circuit changes, it was a record that was to stand for 39 years.

Richard did just two more races, winning the Österreichring 1000Kms, sharing with Pedro Rodriguez, though he is the first to say the victory belonged to his team-mate.

“Honestly, it was Pedro’s race. There had to be two drivers so I just minded the shop while he took a break. That was all I did.”

That race has gone down rivalling the Brands Hatch 1000Kms race the previous year as perhaps Rodriguez’s finest drive. Two weeks later he was dead. I remember Tony Southgate telling me, “We had this BRM sports car which we were going to race in the Interserie event at the Norisring. But we only had one engine and we blew it up on the dyno. I had to ring Pedro and say, ‘Very sorry, but we haven’t got a car for you to race.’ He replied, ‘Don’t worry, I’ve been offered £1500 to drive this Ferrari.’ Had that engine held, we might have had him for a little longer.”

Attwood was back at Le Mans in 1971, alongside Herbert Müller in a John Wyer/Gulf 917K; they’d finish second… but Attwood would return – in 1984

In the event, driving Herbie Müller’s Ferrari 512 M, he crashed, the car caught fire and that was that. Not that this in any way cemented Attwood’s decision to retire. He’d already made his mind up. He did the final race at Watkins Glen, the last time a factory 917 would contest a round of the World Sportscar Championship, and came third sharing with Derek Bell despite the latter having to jury rig a broken throttle cable at the side of the track. He was out. He had survived and never regretted his decision.

Today, Richard Attwood is as he has always been for all the years I’ve known him: thoughtful, considerate, kind, articulate and modest in a way you do not expect from pro racing drivers who’ve reached the top of their sport and, above all, bloody funny.

As we’re preparing to leave he suddenly stops and says, “Hang on, I’ve got something to show you…” He then produces an envelope and removes a sheet of headed paper, the name on the top familiar. It’s a handwritten letter of birthday wishes from Wolfgang Porsche, chairman of the Porsche supervisory board, son of Ferry Porsche and cousin of Ferdinand Piëch who designed the 917. I can tell by how carefully he is handling it how much it means to him that, 55 years after he helped deliver Porsche’s first win at Le Mans, it still matters enough to the company for him to be recognised in this way. Given what he went through in that race, and the same one the year before, it is absolutely appropriate that it should.