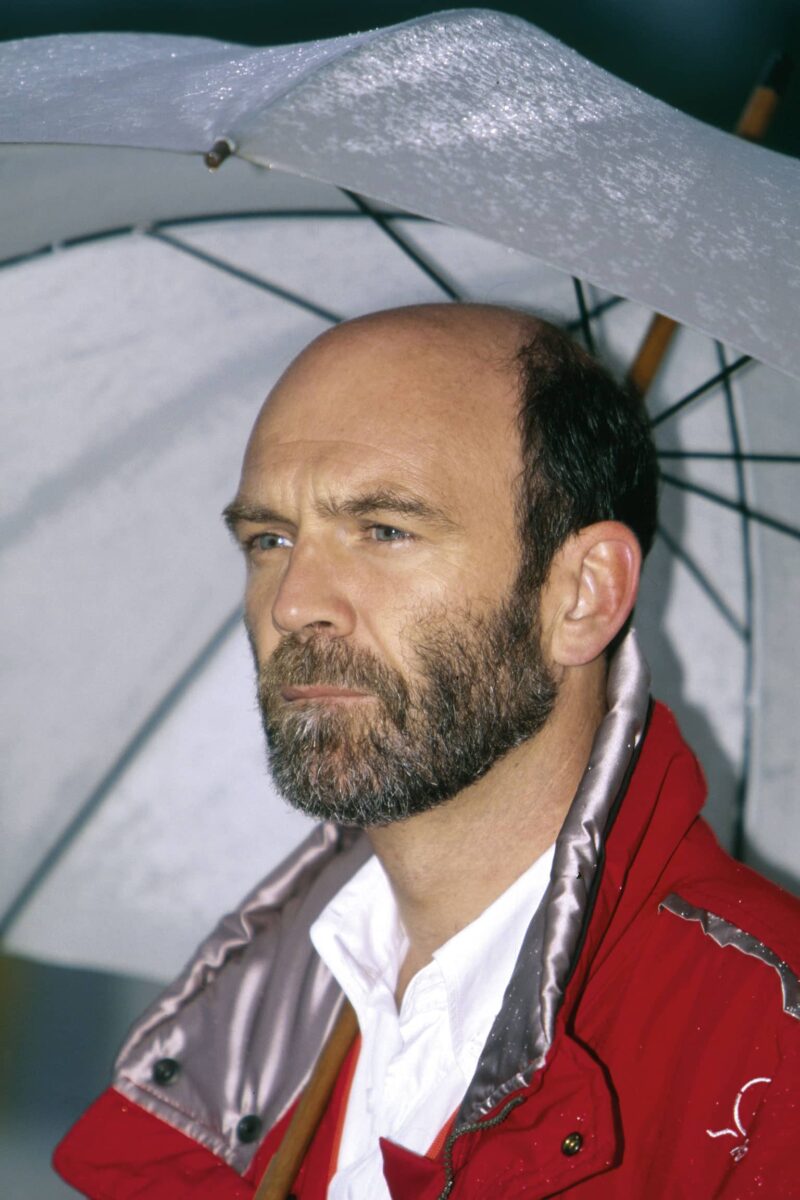

Lunch With... Dr Wolfgang Ullrich

Synonymous with Audi’s success in touring car and endurance racing, he’ll be chasing the company’s 13th Le Mans win in 15 years this June

James Mitchell

Being a racer, and being a winner, takes many forms. The man in the cockpit climbs onto the podium and sprays the champagne, and he gets most of the glory. But without the serried ranks lined up behind him who have used their own skills to get him there – designer to aerodynamicist, engineer to strategist, sponsorship hunter to pit crew and even personal trainer – that champagne would never get sprayed. Motor racing at its highest level has always been a team sport, even if the media find it easier to focus their attention on the individual.

To pull those disparate specialists into a cohesive whole, to unite and motivate them, all the best teams have a father figure. This man, at his best, will be able to draw on a variety of talents. First, he must have the business savvy and the persuasion to convince the suits around the boardroom table, whether they be sponsors or proprietors, that the millions he wants to spend on racing will produce a commercial benefit worth even more millions. Then he will need the engineering ability to conceive his own vision of the car, and gather around him the design talent to convert that vision into reality. This is all before we get to hiring and managing the right driving talent, pulling together the race personnel that will allow cars and drivers to maximise their potential, and building speed and reliability through testing and racing to move forward towards a common goal.

That goal, in the case of my lunch guest this month, is what many regard as the world’s greatest motor race: Les Vingt-Quatre Heures du Mans. Dr Wolfgang Ullrich has directed and overseen victory at Le Mans an extraordinary 12 times in the past 14 years, an unrivalled achievement for one man. There have also been multiple endurance victories around the world, from Fuji to São Paulo, from Sebring to Spa, as well as championship glory in DTM, BTCC and Super Touring series around the world. For more than 20 years Wolfgang has been Audi’s Director of Motorsport, but for him there is no question of this senior role allowing him to keep his suit on and delegate to a subordinate the tense, on-the-job, minute-by-minute management of each race. This June, at the age of 63, he will be in his overalls at Le Mans as always from Saturday morning, doing a 35-hour day in the Audi pit and directing every lap, every pitstop, every strategic decision until the finish flag on Sunday afternoon. Just as much as the men in the cockpits of the R18 e-tron quattros, Dr Ullrich is a racer.

Audi’s hedge-betting R8R and R8C at Le Mans in 1999

Audi Sport

At the track he is a serious, authoritative man, totally focused, even forbidding, and very much the team leader. But having accepted my invitation to a bowl of pasta at his favourite Italian restaurant, a stone’s throw from the giant Audi factories at Ingolstadt, Wolfgang relaxes into the role of a favourite uncle: friendly, courteous and charming, with frequent bursts of self-deprecating laughter. That makes him, in my experience anyway, a typical Austrian.

He was born in Vienna in 1950, and credits his grandfather with sparking his interest in technology. “At home he was always working on something – repairing a neighbour’s washing machine, or taking something to pieces. As a child I spent hours watching him. And at each step he explained to me what he was doing, to make sure I understood. I’d always loved cars, and I went on to do an automotive engineering degree at the University of Vienna, which makes a speciality of that subject. Austria is a small country, but it has a long heritage of automotive design: Dr Ferdinand Porsche was Austrian, and so was Hans Ledwinka [whose streamlined road car designs for Tatra were truly innovative]. It’s in our culture somehow. If that’s what you want to study, you don’t need to go abroad: you can get a very good degree in Vienna.

“After my degree I went on to a doctorate, doing various specific projects for the motor industry. My first contact with motor sport came when the Technical Institute, as an independent body, was asked by the FIA to investigate the water injection that some of the new F1 turbo engines were using. There’d been an appeal from a normally aspirated team about its legality, and it landed on my desk. I had to contact all the engine suppliers and analyse their systems, and this got me close to the technical heart of top level racing.

“When I left university I joined the Austrian manufacturer Steyr-Daimler-Puch, but I still wanted to get into motor sport, and using one of my contacts from the water-injection project I approached Renault. I had a good meeting with the people at Viry-Châtillon, and soon after that I got a verbal offer to join their F1 team. But a week later came a letter to say that it had been a bad year for the automotive industry generally, Renault’s F1 budget was being heavily reduced and the firm was having to sack people. There was nothing they could do and the offer was withdrawn.

“But another contact got me a job at Porsche, which was then doing the TAG turbo engine for McLaren. I was working alongside the guys who did that engine, but I didn’t have much involvement, just some crankshaft calculations, things like that. From Porsche I did some work for a catalytic systems supplier, and then suddenly, near the end of 1993, I was contacted by an old friend from university, Herbert Demel, who was then head of technical development at Audi – he later became CEO. He said, ‘Come and run Audi Motorsport’. So I came to do the same job I do today. I haven’t made any progress at all! [Uproarious laughter.] Although then it was 65 people, now it is 265. More people, more cars, more classes of racing. And in 20 years, yes, we have won some races.

“But it very nearly didn’t happen at all. On the Friday afternoon I left my previous job and travelled here, ready to start my new job on Monday morning. And on Sunday evening I had a call from Demel. He had some bad news for me. There had been an Audi main board meeting on the Thursday, and because of the general recession in automotive markets they had approved the decision to withdraw totally from all involvement in motor sport. ‘But’, said Albert, ‘If you can persuade them in the next few days to change their minds, if you can come up with something worthwhile for less money and sell it to them, you will still have a job.’

“So from the first I had to work very hard to keep Audi in racing. I proposed a smaller programme in Super Touring, with a drastically reduced budget but using local importers as far as possible. We started winning straight away, although not in Germany, and then in 1995 Frank Biela won the one-race World Touring Car Championship at Paul Ricard. In ’96 we went into your BTCC with Biela, and he pretty much dominated it. That year in late September Frank won the last BTCC race at Brands Hatch, so we had the titles for drivers and manufacturers there, and the same day Emanuele Pirro won the last two rounds of the German Super Touring Championship at the Nürburgring, clinching that title. So we sent a plane to Brands, picked up Frank and brought him back to the ’Ring. We had a good party.

“The Super Touring rules kept you pretty close to road-car spec, and in different countries we were up against BMW, Ford, Alfa Romeo, Opel, Toyota, Nissan, Renault, Honda, Peugeot. It was all very competitive. We ran in seven championships, including Australia, South Africa, Spain, Belgium and Italy, and we won them all. In each case it was with a national importer team, but working with a group of our own people from Audi Sport.”

Historic diesel victory at Le Mans in 2006

Motorsport Images

After such success in touring cars, an endurance sports car programme was the next step. “Audi had by then a lot of experience in touring cars and rallying, but we had no experience of Le Mans at all. At the end of 1997 I heard that Reinhold Joest, whose organisation had run Porsches so well for so long, might be available because Porsche was reducing its LMP programme. In fact Joest’s Porsche-powered privateer entries had won Le Mans in ’96 and ’97, and nobody ever thought that Reinhold would move away from Porsche. But I called him, we met, we signed a contract, and we’ve worked together ever since.

“At first we tried two different approaches in endurance racing, the open R8R and the coupé R8C, both using a twin-turbo 3.6 V8. In England we took over the old TOM’S Toyota factory in Norfolk, which we wanted because it had all the equipment for carbonfibre manufacturing, and we had none of that in Germany. We called it Racing Technology Norfolk. We built the R8Cs at RTN, and Richard Lloyd and Audi Sport UK ran those, while Joest ran the R8Rs. At Le Mans in 1999 the coupés had gearbox problems, but the Joest cars finished third and fourth, so that was a good start. It was a conservative car and we never expected to win: we just wanted to get through to the end. We had to carry the reputation of a brand that didn’t have technical failures in racing, so we were taking a big risk. But in those days – it’s 15 years ago now – you could reckon that if you got your sports-prototype through the race without a major repair, you’d be on the podium. You had to be patient: let the others race, let the others break, don’t get nervous if you are two laps behind.

“But for 2000 we knew we had to make a big leap. That was the R8. It brought us victory at Le Mans first time out – in fact we finished 1-2-3 – and that car went on to have a racing life, a winning life, of six seasons. We had to develop it year by year, of course: better aerodynamics, TSFI (turbo stratified fuel injection), lots of on-going work. But the basic concept didn’t change. We incorporated a detachable rear end because we’d analysed all the reasons why top teams had retirements at Le Mans, and the most frequent mechanical failure was the gearbox. With our gearbox partners we’d come up with a very good transmission, but we couldn’t guarantee to make it bullet-proof. So we said, let’s try to have a gearbox that we can change without losing more than a lap, which at Le Mans is less than 3min 40sec. That was our target. It was a brilliant concept: an entire rear end sitting ready and waiting in the pit, gearbox, suspension, driveshafts all assembled, with the geometry and set-up exactly right, so that if you unbolt the old back end and put on the new one, the car will drive exactly as it did before.

“Because of this we won many races that we would have lost, not because of gearbox failures, but because of accident damage. If the driver could somehow nurse the car back to the pits we could send him out again in less than four minutes. But the ACO [Le Mans organiser l’Automobile Club de l’Ouest] decided that it did not follow their idea of endurance. So, although we hadn’t had a single gearbox failure and had only used the facility because of accidents, after 2005 they banned it.

Early days: Ullrich’s first season with Audi back in 1994

Audi Sport

“It was in April 2001, testing at the Lausitzring, that we lost Michele Alboreto. That was the most negative day of my career: first, because when something like that happens it is the worst, and you will do anything to avoid it. And second, because it was Michele. He’d already won Le Mans for Joest in 1997, aged 40, and when Joest and Audi first got together Reinhold recommended him to me. From the start of our endurance programme he was a friend and guide to our younger drivers, and put a lot of personal effort into working with them and passing on all his experience. He was fourth at Le Mans for us in 1999, then third in 2000. And his character and his approach made him invaluable in testing. I could ask him exactly what he thought, and he would give me an intelligent, constructive answer. If we had a difficult day’s testing he was always the last to leave the circuit. He would have a good word for everybody working on the project, because he felt so much part of our team.

“At the Lausitzring you have a banked test oval, and you have an infield handling track. Our routine that day was to do two high-speed laps of the oval, then two laps of the infield track, then into the pits. Then out, the handling track, onto the oval, and then in. He came in, we changed tyres, he went out onto the handling track and he picked up a slow puncture. But in the slow section he didn’t feel it. Then onto the oval the pressure was already too low, and at high speed the tyre failed. After that we developed our tyre pressure monitoring system, which has been on all our race cars ever since.”

Joest-run R8s finished 1-2 at Le Mans in 2001 and 1-2-3 in 2002, but now there was a new string to the VW Group racing bow: the Bentley Speed 8. Designed by Peter Elleray, who had been responsible for the Audi R8C, it was built at RTN in Norfolk. Although it used the Audi V8 engine, it had several key differences, including Xtrac transmission and Dunlop tyres. After earning third place in 2001 and fourth in 2002, Bentley triumphed at Le Mans in 2003.

“Richard Lloyd was team principal, and the team manager was John Wickham. We’d worked with John ever since we first came into the BTCC. Apart from the engine the whole car was done in England, so it was very much a Bentley project. But we supported it and our people were involved: it used the synergies of the group. And to help run the cars at the race we dressed up some good Joest people in green overalls. But 2003 was a busy year because, although we had no works/Joest cars we had R8s from Champion, Audi Sport UK and Audi Japan. The Bentleys finished 1-2, the Champion car was third and the Japan car fourth.” The huge British contingent in the crowd was ecstatic as Tom Kristensen, Dindo Capello and Guy Smith led home Johnny Herbert, Mark Blundell and David Brabham in the first Bentley victory at Le Mans for 73 years.

In 2004 and ’05 the R8 continued its winning ways at Le Mans. Officially customer teams now ran the cars, but in most cases they came direct from the factory. “Team Goh, for example, sent its Japanese mechanics to Ingolstadt for four months to build up the car, learn everything about it, learn to work with our people. And when they all got to Le Mans it was like one squad, a mix of our guys and the Japanese, the English and so on.”

Meanwhile Wolfgang and his team were already working on their dramatic new concept for 2006: the R10 turbodiesel. This was a major initiative for Audi, and perhaps the most dramatic way yet to strengthen the marketing message of the brand through motor sport. “Diesel technology was now vitally important for our road car programme. Its image was economical, reliable, responsible; but it wasn’t sporty. We wanted to change that, and we knew it would be a great story if we could be the first to go to Le Mans with a diesel car and win. But first we had to persuade the ACO, whose rules stipulated only one type of race fuel, that it was worthwhile, not just for us but for others.”

The R10 TDi was raced first in the Sebring 12 Hours in March 2006. Audi had won Sebring with the R8 for the past six years running, but this was a trip into the unknown. Both cars, run under the banner of Audi North America, had problems in practice and qualifying, and in the race one was out after four hours with an electronic failure. “The other car said to itself, ‘OK, now it’s race day. Time to forget my problems and do my job’.”

Le Mans win number 12, 2013

Audi Sport

It took Kristensen, Capello and Allan McNish to a comfortable win. “But for us that race was just part of the development programme. Straight after winning the 12-hour race, and without touching the car, we were back on track at 8 o’clock on Monday morning and we did another 12 hours. And 24 hours at Sebring is tougher than 24 hours at Le Mans.”

Of the diesels that went to Le Mans that June, one had sundry problems that delayed it enough to drop it to third at the end, behind the fastest Pescarolo. But the other, driven by Biela, Pirro and Marco Werner, won by four laps. History had been made. The same trio won in 2007, but the other two cars retired after separate accidents – remarkably, the first time a Joest-run Audi had retired at Le Mans. That year Peugeot had arrived with a pair of its own turbodiesels, and got one home in second place. And in ’08 Le Mans became a serious battle between these two manufacturers, with Peugeots qualifying 1-2-3 and starting as favourites. At the flag the McNish/Kristensen/Capello Audi had it by a whisker, with Peugeot second and third, Audi fourth, Peugeot fifth and Audi sixth. It had been a close-run thing.

And then came 2009, and the only time in his involvement in the race since 1999 that a car ultimately directed by Wolfgang Ullrich has not won Le Mans. To vanquish Peugeot, Audi developed a new car, the R15. “It was a completely new aero concept, with a lot of the air that we would normally try to get around the car passing through the car. That allowed us to raise downforce to a new level. We have a wonderful partnership with Michelin, which worked with us to try to maximise the potential, but to find the right set-up for Le Mans we had to set the cars up very stiff, and that compromised the handling. So in absolute terms we lacked pace. Peugeot finished one-two, we salvaged third place. It was a big disappointment: but afterwards we had a good party with the Peugeot guys.”

For 2010 the R15 had become the R15-plus, with the previous year’s aerodynamics radically rethought. “And Michelin’s rubber now worked so well with the car that we could do five stints on one set of tyres.” This time everything went to Audi’s script: the R15-plus TDis finished 1-2-3, while Peugeot had a nightmare of engine failures. “It was not how we wanted to win, and when the last Peugeot blew up I could not really find a big happy smile. I remember one of my engine guys was grinning when it happened, and I said to him, ‘Think about how it would feel if it happened to you. We want to win in a straight fight, not like this.’ I always had a good sporting relationship with Peugeot’s Oliver Quesnel, and their engine man Bruno Famin.”

For 2011 new rules downsized the engines from 5.5-litres to 3.7-litres, and a totally new car was needed. For the R18 Audi opted for a single-turbo V6 and coupé bodywork. The race started badly when two cars were in horrifying accidents. “Allan was running just behind Timo Bernhard. The GT Ferrari they were lapping only saw one Audi in his mirrors and moved across on Allan, who went cartwheeling over the barriers. Our cars are very strong, but we don’t want to prove it like that. Then Mike Rockenfeller crashed late on Saturday night, so for the last 17 hours we only had one car. Then in the closing stages André Lotterer was leading by a small margin when, a couple of laps before he was due in for a splash-and-dash, we saw from our systems that he had a slow puncture.

“If we’d brought him in at once that would have committed us to an extra fuel stop, and we would have lost the race. We had an urgent strategic discussion and Tom Kristensen was part of that: his input was key. When drivers have retired from the race, once they’ve showered and changed, they always want to stay in the pit as part of the team until the end. So we nursed Lotterer round for two more laps, monitoring the tyre pressure and keeping him informed. Then he came in, took on fuel plus a full set of tyres, and we got him out with only a 6sec lead. He went flat out, and at the flag, after more than 3000 miles of racing, he had just 13sec over the first of the three Peugeots.

“Tom is an exceptional guy, and there’s no question that as a driver he is on a very high level. But I must tell you about when he first joined us in 2000. He came in as a Le Mans winner and was very keen to make a good impression on me. I put him with Emanuele and Frank, and their first race together was Sebring. Of course he wanted to qualify quickest, and when he went out in practice Emanuele and I got on a golf cart and went out to watch. On his second lap Tom came fantastically quickly down into Turn Two, and Emanuele and I looked at each other with the same thought: ‘He’s not going to make it’.

With long-time ally Reinhold Joest at Le Mans in 2012

Audi Sport

“Tom went straight off, into and under the tyre barrier, and disappeared completely. When the dust settled all you could see was this huge pile of tyres with just the rear wing sticking out. There was one marshal the other side waving a flag but nobody else seemed to be doing anything, so Emanuele and I climbed over the fence and started digging into the tyres to get him out. Tom tells the story: he’s in the cockpit, it’s all gone quiet, it’s all dark and then the tyres open up, it gets light and what does he see floating above him? The face of his new boss…

“Tom is the only one of my drivers who has been able to do LMP and DTM at the same time, and be competitive in both. That’s unusual, because the disciplines are completely different. A fast driver will be fast in any type of car, but it’s not just about the lap times. It’s about handling traffic. In DTM you’ll be fighting with 12 or 15 cars that can all be within a couple of tenths. At Le Mans there is a big speed differential between you and the LMP2 cars, and more with the GTs. You have to approach each overtaking manoeuvre quite differently. Even a small contact with another car is probably going to spoil your race, maybe break a fin or something. You have to feel what the other guy is going to do in each fraction of a second. It’s your job to learn and remember how the driver of each car is likely to behave, because in a 24-hour race you might pass him 50 times. If you can’t be sure how he will react as you catch him, it’ll spoil your rhythm.

“Who shares with whom in the Audis is always my decision. There’s some psychology involved, I suppose, and I try to put similar driving styles together, but more practically it’s about size. We put tall Mr Biela and little Mr McNish in the same ALMS car for a full season, and it worked well because Allan had an extra seat that dropped straight in over Frank’s seat. But if you have two drivers who work well as a pairing, and you put a third driver with them who doesn’t fit in, then the good pairing is gone as well. The best driver teams build up a good level of friendship and end up spending a lot of their free time together, as working colleagues who genuinely like each other. Those are the teams that work really successfully as a unit.”

McNish has been a stalwart of Audi’s endurance racing programme for 11 seasons, but since the end of last season he is no longer on the roster. Was Wolfgang surprised by the Scot’s decision to retire? “I wasn’t surprised when he said he wanted to talk to me about it, but I didn’t necessarily expect that he would stop completely. But having discussed it with him, I think it was the right move. I wanted to keep him for 2014, but he felt that was the moment to stop everything, no testing, nothing, and I did not try to make him change his mind.”

Mike Rockenfeller won last year’s DTM title and became the sixth Audi driver to have done so since 2004

Audi Sport

Inevitably our conversation has concentrated on Le Mans and endurance racing, but Audi’s activities in touring cars and DTM have continued alongside its LMP programmes. So I ask about the notorious DTM race at Barcelona in 2007. The Deutsche Tourenwagen Meisterschaft was then a straight fight between groups of teams each running C-class Mercedes-Benzes or Audi A4s. “At the penultimate round in Spain there was a lot of tension between the Audi drivers and the Mercedes guys, and the gossip before the race said that a couple of the Mercedes drivers had been given the job of getting rid of our people. And in the race, that’s what happened. After three separate incidents in which our front-running cars were put off the track by Mercedes men, I could hear our drivers saying over the radio to their engineers, ‘Give me permission and I will drive this one off.’ That’s when I said, ‘We don’t do as they do, and the world shall see it’. I got on the radio to each of the seven Audi drivers who were left and gave the order: stop racing now, drive slowly into the pits and retire. Let Mercedes carry on playing on their own. So that’s what happened. It’s the first time I have ever seen [former Mercedes competitions boss] Norbert Haug completely speechless.

“It wasn’t an easy decision, and it wasn’t fair to the spectators, who’d paid to come and see a proper race. It was like a whole football team walking off. But I didn’t want us to play that game. So Mercedes scored all the points that day, and it could have wasted all we had worked for that season. But in the final round at Hockenheim three weeks later we clinched the championship with Mattias Ekstrom.”

Back to Le Mans, and the arrival in 2012 of hybrid technology both for Audi and for Peugeot’s replacement as its most serious rival, Toyota. The Audi system, developed with Williams Hybrid Power, moved to part-time four-wheel drive. The engine powered the back wheels conventionally, while at the front kinetic forces generated under braking were converted into electric energy and stored in a spinning flywheel. Under acceleration, this power was returned to drive the front wheels. Wolfgang hedged his bets by running two R18 e-tron quattros and two conventional R18 Ultras, and the hybrid cars finished one-two, with the Ultras third and fifth. The Toyotas both crashed early on. In 2013 the order at the front was Audi-Toyota-Audi-Toyota-Audi, but celebrations were subdued because of the death just after the start of GT racer Allan Simonsen.

So to this year’s race, which looks like being the most technically fascinating 24 Hours in living memory, driven by a dramatically revised rulebook that is intended to keep the race meaningful in a changing world. How does Wolfgang feel about the imposition of the new rules, which are committing the manufacturers to ever more development expenditure?

“It’s what we wanted. This new rulebook happened because we and the other manufacturers pushed for it – just like we pushed hard for diesel fuels a few years ago. Road car design is concentrating more and more now on the efficient use of energy, and our racing – technically as well as on the marketing side – has to support the brand, it has to have meaning and relevance for our road cars. The ACO and the FIA wanted that relevance for the future, too. So four years ago we started to work on it together. We all agreed that the way forward is to reward any reduction of energy wastage, and the new rulebook is a significant step in that direction.

“What is interesting is that the three big teams are each approaching the challenge differently. The Porsche is a V4 petrol turbo, the Toyota is a normally aspirated V8, ours is a V6 turbo diesel. And we have further developed our flywheel system. No more do the rules limit the amount of horsepower we have available. Nor do they limit the amount of air going into the engine – that would be crazy, because air is free. What the rules do is give us a set amount of energy, and the car that can go farther and faster on that amount of energy will win the race. We have 30 per cent less fuel available to us than last year, and our target is to achieve the same speed and distance as we did in 2013. Each year’s rules will reduce the energy permitted: less in 2015, less again in 2016.

“It’s not just the technical challenge, but a human challenge too. All through the race a sonic system controlled by the organisers will continuously measure the amount of fuel going into every car’s engine. If your car uses its fuel too quickly you have three laps to bring it down to the correct average, or you will incur a stop-go penalty. The driver gets information on the dash so that he can optimise his lap time against fuel usage, and if he has used too much because, say, he has been fighting another car, he knows how much he must save. All last season we were working on concepts to use less fuel without increasing lap times at all, retraining the gas-guzzlers if you like, and for them it’s another personal challenge. So now the driver will play an even bigger role in determining between defeat and victory.

“Motor sport is a unique proving ground. Unlike some motor manufacturers who promote their brands through racing, Audi Sport is not a separate company from the parent; we are intertwined with the road car technology. We are doing our development under the public gaze, and we have to ensure first that it works, second that it is competitive and third that it wins. Then, three years later, we can tell our customers that lessons learned on the track really have come through into their new road car. Energy efficiency is a major example – TSFI has already saved millions of gallons of fuel on our road cars – but there are others: like headlights. On the R18 we went to LED matrix lights, and this year we also have the laser lights that are sensitive to the steering. You’ll see this on our road cars soon.”

A key part of Wolfgang’s job continues to be persuading Audi’s main board, and indeed that of the VW Group, that the massive expenditure on endurance racing is justified, especially when new rules make previous cars obsolete and ramp up design and development costs. “With the marketing people I work out what makes the most sense to support the brand, its technology and its message. Then, every year,

I have to submit my plans to the board: this is what I want to achieve, this is the budget I need to achieve it.” So is there any danger that, with Audi and Porsche both ultimately part of the VW Group, a suit at a board meeting is one day going to ask why they are spending all this money competing against themselves? “Each brand is completely different, but both have important Le Mans history. The new technology now allowed in the rules encourages different concepts to be explored within the same group, different answers to the same question. And, even in the same family, you have competition between brothers.”

Would one of the brands ever be diverted off in the direction of Formula 1? “We discuss it every year. Up to now we have always decided not to do it, and the relevance of Le Mans to road car development has reinforced this policy. But, you know, things can change…”

Wolfgang gets precious little free time, especially during the season, and what he does get he likes to spend with his family. “I have a big mix at home. From my first family I have a 33-year-old daughter, with two grandchildren, and my son by my second marriage is now 14. He never misses Le Mans. He has already been 14 times: the first time he came he was three months old.

“As for me, I am very much looking forward to the second weekend in June. The Le Mans 24 Hours is what I love. This year it will be specially fascinating, and specially hard to predict. All the way up to Sunday afternoon, and the final flag.”

Dr Wolfgang Ullrich

Career in brief

Born: 27/8/1950, Vienna, Austria

1993 Appointed Head of Audi Motorsport in November

1994-1999 Super Touring programmes in several countries, multiple title successes

1999 Audi enters Le Mans, R8Rs taking 3rd and 4th

2000-02 Le Mans winner

2004 Audi joins DTM as factory team, wins title; first of five straight Le Mans victories

2010-13 Audi increases Le Mans win tally to 12

2012-13 Audi scoops revived World Endurance Championship