As usual, the rally started from various cities spread all over Europe, of which the most popular from the point of view of competitors starting from there was the Norwegian capital of Oslo, from which four of the American Falcons, including Ljungfeldt, started as well as the two red Saab Sports of Erik Carlsson and his wife, Pat Moss. The Swedes, Tom Trana and Carl-Magnus Skogh who were driving Volvo PV544s, and Donald and Erle Morley also started from Oslo, as did the Scania-Vabis-entered VW 1500Ss of Pauli Toivonen and Bernt Jansson. These latter cars were fitted with an extra German-made heater. in the front boot lest the weather proved too cold in the South of France.

For the first time in many years, there was to be a start from a town in Russia and the place selected for this honour was Minsk. Quite a large proportion of British entries seemed attracted to this city on the Steppes, and these included Paddy Hopkirk in the Cooper S, Sidney Allard and his son Alan in Cortinas, Raymond Baxter in a Cooper and Michael Frostick in an Imp. It was to be the first time too that there had been a Russian entry in the Monte Carlo Rally, and no less than five cars were entered, of which three were the big 2 1/2-litre Volgas and the other two were the smaller 1,360-c.c. Moskvitchs. These did not, unfortunately, make a particularly impressive rally debut, as they had obtained Greek maps to get them as far as Belgium (primarily one supposes due to the resemblance between the Greek and Russian alphabets) but did not have any maps to take them through France. Thus it came as no surprise to learn that two of them at least had travelled straight down the N7 to Monte Carlo. This was a gallant effort, nevertheless; to try and compete in a major International event in cars of practically pre-war design and without maps, and the Russian crews received a hearty ovation for their efforts at the end of the prize-giving. One hopes that they will not be dissuaded from trying again and that they will be better prepared next time.

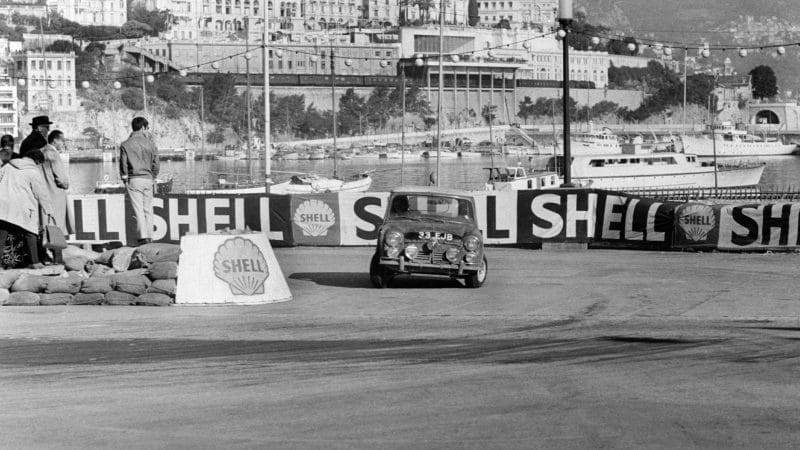

Hopkirk/Liddon Mini scampers through the snow on the Col de Turini

BMW

The next most popular – or should one say populous ? – start, after Oslo, was the French capital, Paris. The other four Falcons, whose drivers were Peter Harper, Peter Jopp, Graham Hill and Anne Hall, had chosen this as their starting point and they were joined by two of the British-built Ford Cortina GTs driven by David Seigle-Morris and Geoff Mabbs. As always, there were a large number of the big Citroën DS19s, both works entered and privately owned, together with the odd Simca 1000 and Renault R8, also privately owned. As far as rallying is concerned, completely new cars were the three Plymouth Valiants entered by the American Chrysler Corporation. These were the first examples of the Plymouth compact to have a V8 engine and their entry marked another milestone in that Scott Harvey and Gene Henderson were the first all-American crew in an all-American Car to compete in the Monte.

The number of entrants who had chosen to start from Glasgow had fallen by comparison with previous years, but there was still the faithful few who could see the mystic attraction of starting in Britain, crossing the Channel and then running down to Monte. Among them were the two works Reliants of Bobby Parkes and Peter Roberts and the works-loaned Rovers of Ken James and Raymond Joss. The only other sizeable British entry was centred on Monte Carlo itself as this had been chosen by the works Cortinas of Henry Taylor and Vic Elford. A similar car had been loaned to Peter Dimmock, of the B.B.C., who was also starting from Monte Carlo, as were the works Citroëns of the French Champions, René Trautmann and Claudine Bouchet.