Page 4

Matters of Moment, March 1997

The next issue of MOTOR SPORT will be one of the most momentous in its history. After months of intensive…

The next issue of MOTOR SPORT will be one of the most momentous in its history. After months of intensive…

If McLaren is to re-emerge as a major force in F1, it will be through improved technology. Without it, argues…

Once the most successful team in Formula One, McLaren has not won a Grand Prix since 1993. Bruce Jones explains…

McLaren's F1 GTR was the car to beat in GT racing in 1995 and early '96. Then along came Porsche's…

In the days when the Formula One stars had time off in the winter, many went down under for fun…

Subaru won the Monte Carlo Rally, but not before a bloody fight with Mitsubishi and Ford. Andrew Frankel was there…

In May, Luigi "Gigi" Villoresi will be 88 years of age, and after a remarkable career he is now the…

Given its recent history, it's amazing that Lotus has made the GT3 so exceptional, but to offer it at such…

Refined performance is the key to the Audi A3 Sport's success, says Colin Goodwin Think of the Audi A3 1.8T…

It's great to drive, but the new Prelude just doesn't look the part. By Stephen Sutcliffe On the face of…

Under normal circumstances, most models have a reasonable lifespan, but when things go wrong some are killed off before their…

F1 96 World Championship Photographic Review. Vine House Books, £21.95 Of similar size to its stablemate, this volume also packs…

Formula 1 Yearbook. Vine House Books, £25 Almost as big as a Palawan offering, this yearbook is packed with pictures.…

Le Mans The Jaguar Years. Brooklands Books, £12.95. Brooklands Books has broadened its range. As well as its incredibly complete…

Cars in the UK Volume Two: 1971-1995, by Graham Robson. MRP, £19.95 The second volume of Robson's incredibly detailed directory…

Collector's Guide: Land Rover, James Taylor. MRP, £14.99 MRP has expanded its literature on Land Rovers to cover the 1948-1983…

Lagonda, by Bernd Holthusen. Palawan, £275 cloth, £750 leather. This is the first of Palawan's "superbooks" not to have been…

Sir, It is indeed a good thing that a driver is remembered by his deeds rather than by his name.…

Sir, Shaun Campbell is to be congratulated for an entertaining and well researched article. Most of the Grand Prix runts…

Sir, Was it a coincidence that your February issue contained a feature on why Ferrari must become a championship force…

Fernando Alonso believes that he is being treated more harshly than other drivers with sanctions from stewards

In 2007 the Paulistas had embraced Lewis Hamilton – a mixed-race tyro chasing the F1 championship in a mixed-race city – but one year on attitudes had changed. He was…

Aston Martin hopes improvements to its car could persuade Sebastian Vettel to stay in F1, but can he reconcile this with his climate crusade?

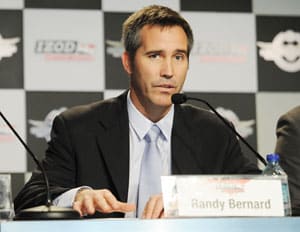

The IndyCar Series has decided to continue with Dallara as its spec car manufacturer for 2012-15. Dallara has committed to build its Indycars at a new facility in Speedway, Indiana…