Revenge was exacted in various ways. Jim Clark – whose one previous drive at Indy was a test session in a 25, an experience he described afterwards as “a bit dull really” despite a best lap of 143mph was compelled to take a humiliating rookie test. In the race itself Gurney started well but slipped back to seventh at the finish, whereas Clark, despite being robbed by yellow flags of much of the advantage of his fewer pitstops, looked set to win until Parnelli Jones’s leading roadster infamously began to leak oil onto the track. Furious complaints by Chapman failed to get Jones disqualified and Clark had to settle for second. A prize purse of over $55,000 helped soothe Lotus indignation. As did an emphatic win in the following Milwaukee race, where Clark led for all 200 miles.

Len Terry would exact his revenge in turn in 1965, when Clark triumphed in the third-generation Lotus Indy car, the 38, to become the first non-American to win the race since 1916. Still, that 1963 ‘robbery’ irks even today. “If they had stuck to their own rules we would have won the race,” says Terry for what must be the umpteenth time, “but I’m biased, of course.”

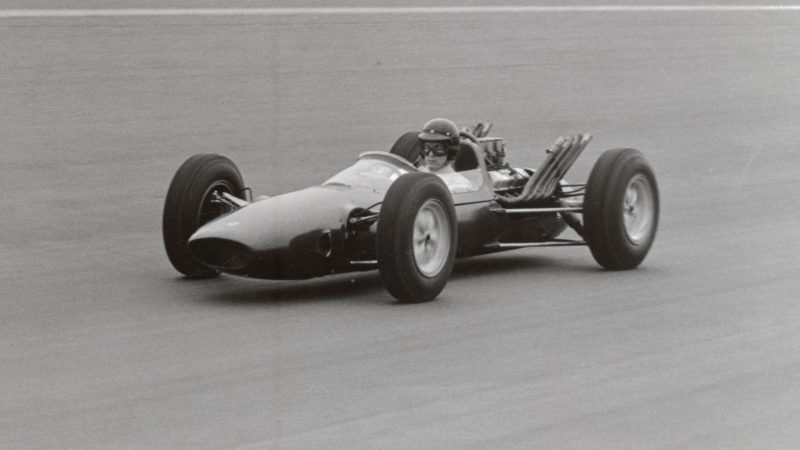

Clark finished second on his first Indy attempt, before winning the next championship race at Milwaukee

IMS

Construction of the 29 was on the ‘bathtub’ principle first used in the 25. To maximise its fuel capacity and so capitalise on the decision to use pump fuel, the chassis ‘sills’ were taller and wider and a saddle tank was added above the driver’s legs, bringing the total capacity, including the small tank behind the driver’s back, to an impressive 42 gallons. Unlike the 25, the tanks were interconnected using a system of non-return valves of Terry’s devising which allowed fuel to flow into the left-hand sill tank but not out of it — other than to the engine! — thereby ensuring that the weight of the fuel load remained evenly distributed through lndy’s succession of left-hand corners.

Ford’s pushrod Fairlane V8 must have seemed pretty crude to Lotus eyes compared to the Coventry-Climax FWMV used in the 25, and its 370bhp from 4195cc (just 88bhp/litre) compared very poorly with the 130bhp/litre achieved by the Coventry unit the same year.