F1's green future — with two-stroke engines?

F1 faces a fight to prove it can adapt in the face of environmental pressures. Dominic Tobin argues that the solution to the problem lies in the sport’s past

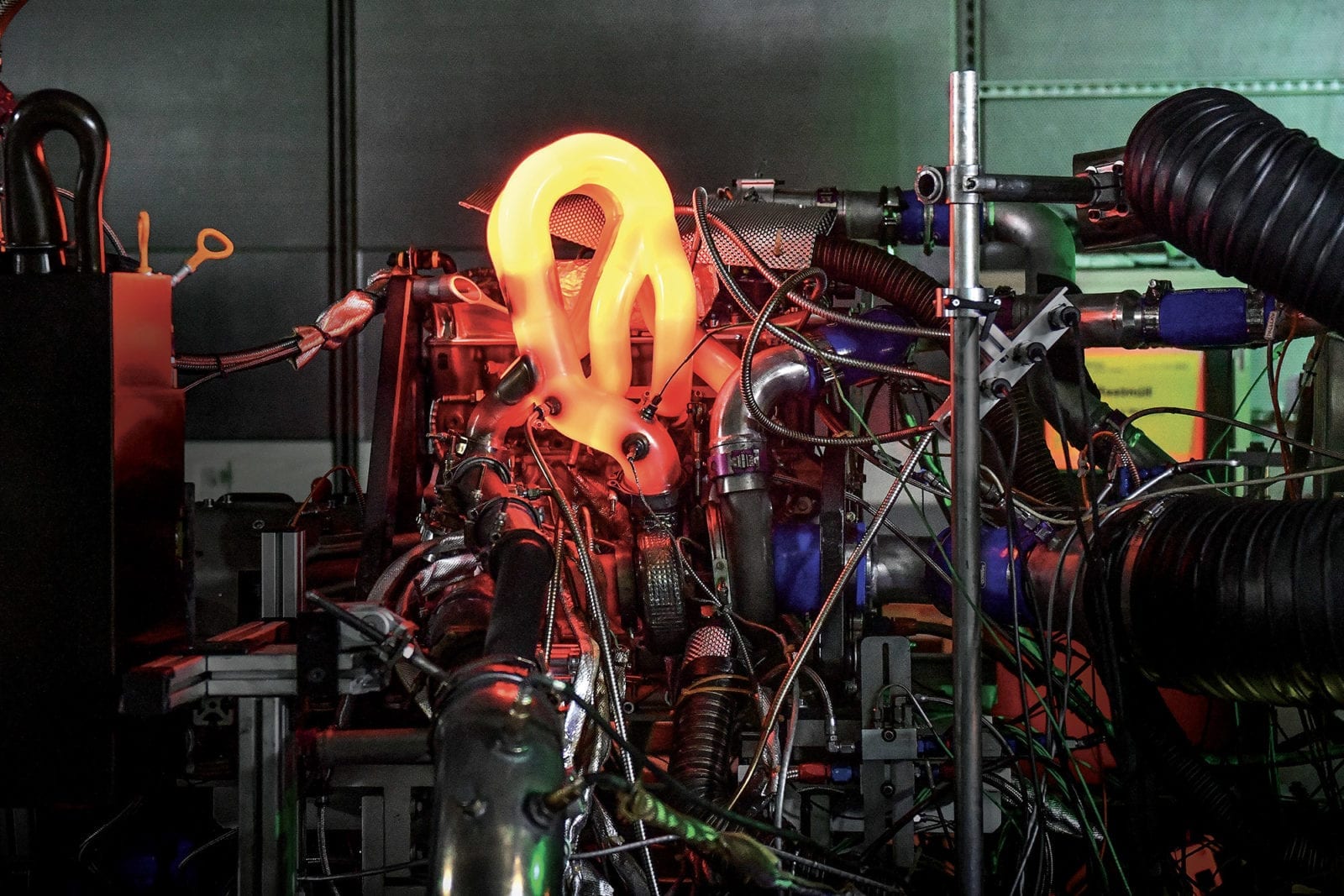

Sign of F1’s future? Audi’s red-hot DTM engine trials low carbon fuel in 2019

Later this year Formula 1 will release its first fragrance collection. And you can bet that the heady aroma of burnt fuel won’t be one of the scents placed on the shelf.

Previously revelling in high-octane entertainment, F1 is now facing questions over its future existence.

Bans on the sale of new conventional petrol and diesel cars are approaching, so manufacturers and sponsors are more likely to put money into Formula E than F1.

The young audience that F1 is desperate to attract are concerned about the world in which they’ll grow up in. Where does that leave a championship that uses seven jumbo jets to transport cars around the world – to then burn fuel at each destination?

Rejecting managed decline or a new electric future, F1 has chosen an emissions- free direction, hoping thereby to retain the excitement, engines and noise. It’s the equivalent of vegan burgers for the green- minded gourmands: F1 without the guilt.

From 2025, we could be seeing cars powered by two-stroke engines, using a zero-carbon fuel, which are more eco-friendly than Formula E racers.

Can Symonds convince doubters about two-strokes?

Sutton

F1 won’t just leave its mark with dark strips of rubber on the track – although those will remain – it will also fund eco-projects in each country that it visits to offset carbon emissions it can’t avoid.

Last year, F1 published a strategy to become carbon-neutral by 2030, which included team factories using renewable energy and a single-use plastic ban at races.

Now Motor Sport has learned more of F1’s plan to reduce emissions on track: engine exhaust fumes account for just 0.7 per cent of the 226,551 tonnes of CO2 emitted during each season, but they are the most visible part.

New engine regulations are due to be introduced in 2025 or 2026 and will bring major change, says Pat Symonds, F1’s chief technical officer.

“I’m very keen on it being a two-stroke,” he said last month. “Much more efficient, great sound from the exhaust, and a lot of the problems with the old two-strokes are just not relevant any more.”

Symonds’ words, at a green motor sport conference organised by the Motorsport Industry Association, came out of the blue.

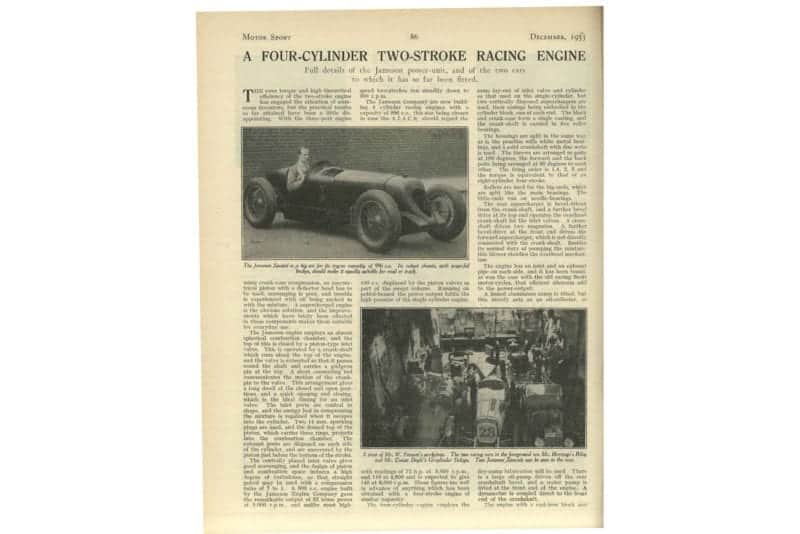

The two-stroke engine was examined in a 1933 issue of Motor Sport

Few would think of two-stroke engines as eco-friendly, given their smoky reputation and long absence from top-level motor sport. Two-strokes disappeared from motorcycle racing in the MotoGP era, and barely featured in grands prix.

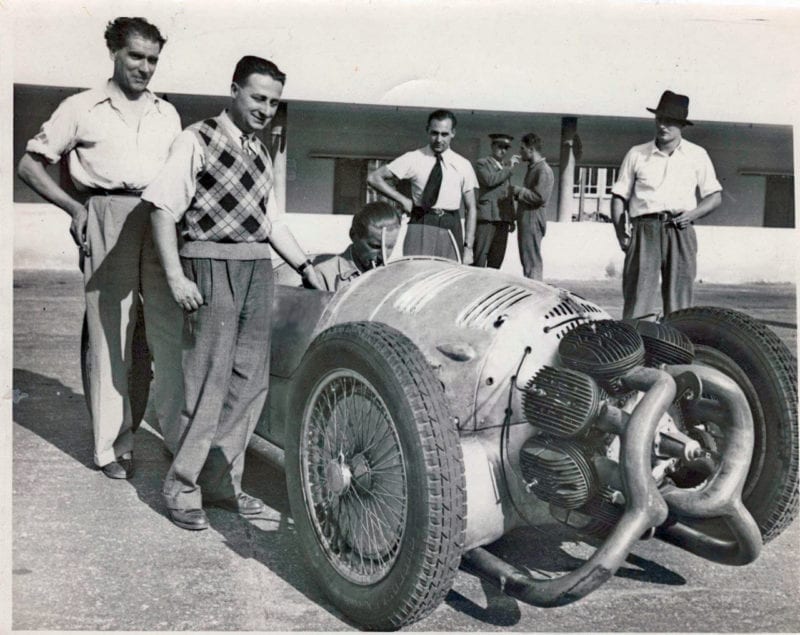

It’s not for lack of trying: the efficiencies of an engine that takes just two strokes to complete a cycle, rather than four, brought a flurry of early attempts to make the technology work. The offbeat Trossi-Monaco took its lead from aviation, with eight banks of 16 cylinders arranged in a radial formation at the front but the airflow couldn’t overcome the overheating issues that come with the design. It failed to race at the 1935 Italian Grand Prix.

That happened a year after Sir Malcolm Campbell couldn’t fire up the two-stroke- powered Jameson Special that he was due to drive at Brooklands.

A two-stroke Alva-DKW did win the Boxing Day John Davy Trophy for Formula Juniors in 1959, but there’s been little since to suggest that two-strokes are the future for F1.

Saab and star driver Erik Carlsson relied on two-strokes in rallying. Here’s the Swede’s 96 on its way to victory in Monte Carlo in 1963

Motorsport Images

Red Bull’s motor sport adviser Helmut Marko said that he was surprised by Symonds’ “carnival speech” comments, adding that he would discuss the proposal with his engineers.

But the advantages of two-stroke engines, their lightness and efficiency, remain and Symonds is convinced they have a role.

“It’s reasonably obvious that if you are going to pump that piston up and down, you might as well get work out of it every time the piston comes down rather than every other time the piston comes down,” he said. “The opposed-piston engine is very much coming back and already in road car form is at around 50 per cent efficiency.

“Direct injection, pressure charging, and new ignition systems have all allowed new forms of two-stroke engines to be very efficient and very emission-friendly.”

Biofuel has been part of the sport for years. Damon Hill drives the Barwell Aston Martin DBRS9 from 2007

Gary Hawkins/LAT Photographic

There are still several years for F1 to argue, discuss, then argue some more about the specification of the next-generation engine, so two-strokes are far from being a done deal.

Whichever engine is chosen will be a hybrid. Motors are likely to be fitted to the front wheels to recover energy under braking. This also reduces the brake load, allowing carbon-ceramic brakes to be used in place of the current carbon components, which produce high levels of particulates. Using the motors for four-wheel drive is out of the question, though, according to Symonds.

Water injection could be used for more efficient combustion, and exhaust treatment is set to improve, reducing toxic emissions.

Symonds wants to set up a working group to develop the specification, in the same way that the 2021 chassis rules were drawn up.

It’s likely that tighter restrictions will limit areas where teams can innovate, with the aim of cutting costs and tightening the competition. The teams will be encouraged to develop specification parts collaboratively.

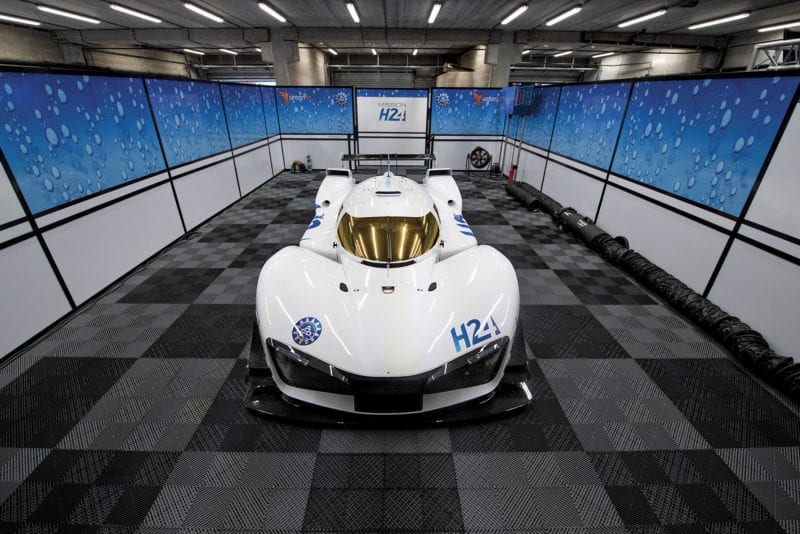

The H24 hydrogen Le Mans prototype

F1 is also looking to pioneer the use of synthetic fuel made in a laboratory, rather than being drilled out of the ground and refined.

Small-scale facilities have already shown that they can filter carbon out of the air and combine it with hydrogen to form the hydrocarbon chains that make up fuel.

When it’s burnt, that same carbon is then released back into the atmosphere. If surplus renewable energy (wind farms can produce more energy than is needed on a blustery day) is used to make the fuel, the process can be made largely carbon-neutral.

The chemical formula can be altered to replicate existing fuel. But increased benefits come when the engine is designed with the fuel, allowing the use of greater compression ratios and improving efficiency.

Factories to produce the fuel industrially are under construction and Symonds believes that F1 could use it within a few years – despite a higher cost. “As soon as there is enough around we should be doing it and we’re not that far away from what we need,” he says.

In time, the planes that transport F1 around the world could also run on the fuel. Limited production and higher cost means that it’s unlikely to appear at fuel pumps soon, but the potential is there to make all road cars carbon-neutral at a stroke – with political help.

EU rules stipulate average carbon dioxide emissions for new cars should not exceed 95g/ km. The easiest way for manufacturers to meet the target is to sell more electric cars.

However, these figures don’t take into account the emissions released when producing vehicles: several studies suggest that making an electric car produces more carbon than a conventional one.

“This will be rethought again in 2023 – hopefully in the right direction,” says Ulrich Baretzky, director of Audi Sport engine development, and the man behind the petrol and diesel engines that secured 13 wins for Audi at Le Mans. “Then electric vehicles will be dead – or some of them.

“They also want to rethink the decision not to adopt renewable fuels as a [measure for] reduction for CO2, which is now the law unfortunately: absolute bulls**t.”

The 1935 Trossi-Monaco had a 16-cylinder, two-stroke engine

Baretzky has already trialled using an alternative fuel in Audi’s RS5 DTM taxi car in a trial at Hockenheim last year. He says the internal combustion engine’s future is secure.

So that exhaust crackle is set to continue beyond the next decade. Hydrogen-powered cars are already under development, with the fuel cell-powered GreenGT H2 running at Le Mans ahead of last year’s 24-hour race. The gas can also be used in a combustion engine, with water being the only emission.

“It might be that the next power unit we produce is the last one we do with liquid hydrocarbons,” said Symonds. “I think there’s a very high chance that there might still be an internal combustion engine, but maybe it’s running on hydrogen.

“I certainly think that the internal combustion engine has a long future and I think it has a future that’s longer than a lot of politicians realise because politicians are hanging everything on electric vehicles.

“There’s nothing wrong with electric vehicles, but there are reasons why they are not the solution for everyone.”