Anthony Davidson: The Motor Sport Interview

“You don’t win Le Mans, Le Mans chooses who wins,” is a phrase Anthony Davidson grew to accept. Now retired, he looks back at his La Sarthe bad fortune, his F1 pride and his sports car glory days

June 19, 2016, La Sarthe, 14.57 CEST. This was the moment that Anthony Davidson knew he was destined never to win the Le Mans 24 Hours. Having just relayed the runaway No5 Toyota Gazoo Racing TS050 Hybrid to Japanese team-mate Kazuki Nakajima, the British ace was then forced to watch despairingly from the garage as the car ground to a halt on the start/finish straight just a lap from the chequered flag. Despite a total of nine top-flight efforts with the likes of Toyota, Peugeot and Aston Martin, Le Mans victory would almost inexplicably escape him. It’s hard to think of another driver more deserving.

After half a life dedicated (perhaps overly) in search of a race seat in Formula 1, Davidson marked himself out as one of the top talents in sports car racing, and that Le Mans near-miss certainly shouldn’t define his career. He’s been a winner at Sebring, a world champion with Toyota, raced in 24 grands prix and is now a key part of Mercedes’ F1 test team. Not bad for a driver who didn’t come from a wealthy background and had to fight tooth and nail for every opportunity.

Before the end of the 2021 season, Davidson, now 42, announced his retirement from professional racing. Shortly after he lifted the third-place trophy for the FIA World Endurance Championship’s LMP2 class, giving his career one final coat of gloss. After all, every professional would rather bow out from the podium than the doldrums.

Motor Sport: Let’s start with retirement. Where has this come from?

Anthony Davidson: “I think Le Mans was a big part of it. For the last few years, it’s been the only race on the calendar that stands out as being the most risky or dangerous. It’s like drivers going to IndyCar prepared to do the street tracks, but preferring to sit out the ovals. Le Mans became a bit like that for me. It’s a dangerous race, and I’ve seen great drivers like Allan Simonsen lose their lives to it, and that stays with you. I’ve also been damaged by it [Davidson broke his back during an airborne crash in 2012] so I know first-hand how things can go wrong there. I never think about the danger of any track, aside from Le Mans. And recently the danger has just become larger and larger in my mind.

“I remember this kid called Button demolishing everyone“

“You also have to ask so much from yourself to get through it, drawing on physical and mental strength and I’ve found myself looking at that race on the calendar at the start of every year and dreading it rather than loving the thought of doing it. That makes it so hard to get into the right headspace. I also found that I was having to dig deeper to get into the wheel-to-wheel fights, mostly because the older you get the more you see the bigger picture. I’m from that generation where we started racing as eight-year-olds, against Jenson Button and Dan Wheldon and Justin Wilson… drivers who were serious competitors right from the word go. For me it’s been a long journey, 34 years trying to be the best. It started to take its toll and I stopped enjoying that intense competition.

“I’ve always been quite hard on myself, and perhaps I’ve focused a bit too much on the negatives rather than the positives and mentally that’s tough when you know things are declining. I still wanted to be the same driver that I was 10 years ago. I didn’t want to get frustrated with myself over that, so the time was right to stop.”

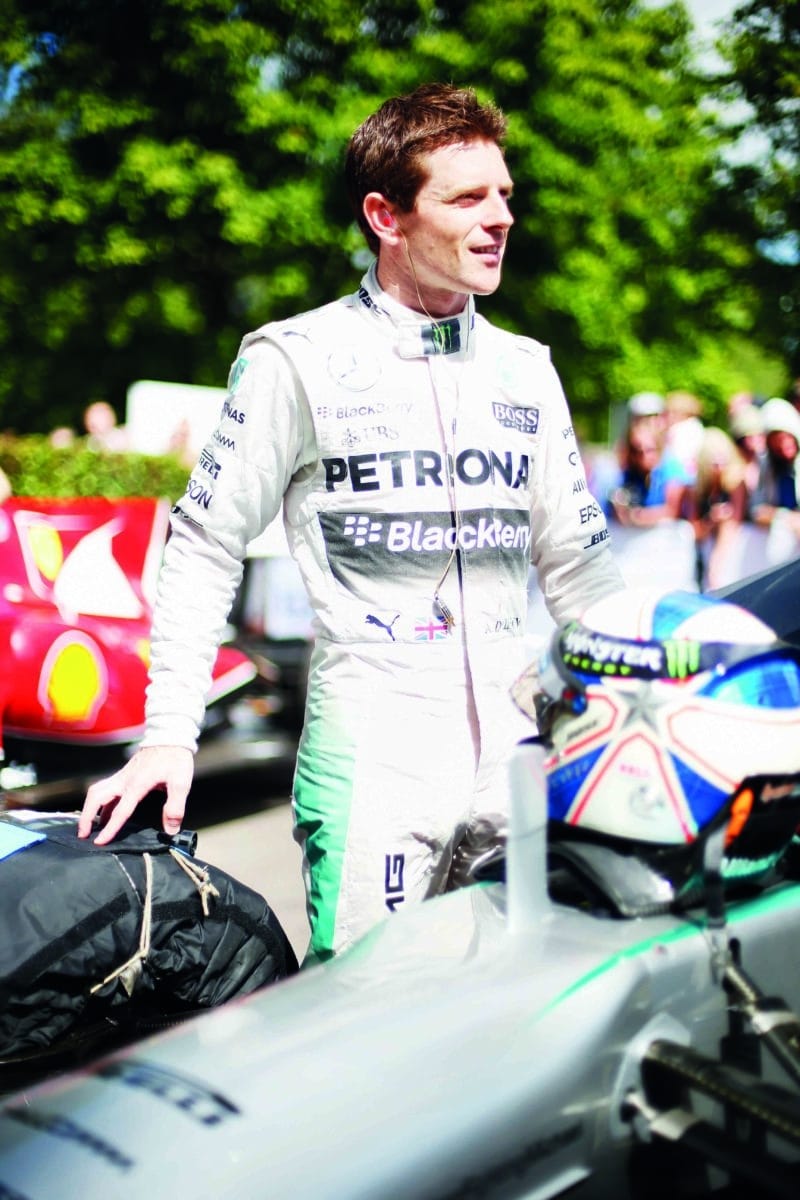

Goodwood in 2015

Charles Coates/Getty Images

Was it just your own perceptions that made your mind up, or were you worried about what other people thought?

AD: “A bit of both. I joined sports cars when drivers like Dindo Capello were already in their late forties, and still racing up front with Audi. Dindo was consistent, but wasn’t setting the world alight, so it was so easy to walk in as a young driver and think, ‘Well, that guy isn’t very good!’ but I remember trying to explain to other young drivers who would arrive in sports cars in their early twenties and turn their nose up at older drivers. I always said, ‘You can only be snidey when you’re their age and still performing at the rate you are right now. Turn your nose up when you’ve held a works drive for as long as they have.’ But I didn’t want to see myself like that, or for people to see me like that: as some old guy clinging on to a drive.”

What’s next for you?

AD: “I’m simulator driver for the Mercedes-AMG Formula 1 team, and I love sim work. Ever since I first drove an F1 car in a testing environment I’ve found it so enjoyable and constructive. I love to see the advancements that come from your work and you learn so much about set-up and the technical aspects, and also how to get the best out of engineers. Feedback has always been one of my strengths, so it’s always clicked for me. Doing the sim work now takes me back to working with Honda and doing what I used to do in real-world tests earlier in my career. And I love talking about the sport through my role with Sky Sports F1, so I won’t be bored.”

You were part of that British ‘Brat Pack’ that emerged during the early ’90s. As you mentioned, Button, Wheldon, Wilson, Gary Paffett… so much talent.

AD: “Those were amazing days. I’m not from a racing family. My father was always a fan of F1, but nobody was directly involved before me. When I came along, I guess he thought it was a great chance to get himself into racing and live it through me. Comer Cadets were quite new over here and for my eighth birthday he booked me a test session around Rye House. Then we bought a kart and it grew from there.

“My brother Andrew raced with me for a while, but he broke his ankle in a crash and decided that was enough. He became my mechanic instead. It was a real family effort through karting, even when we were racing around the world. Those early years were great, being up against drivers like that weekend-in, weekend-out, racing in every weather all over the country. One year we did 46 events in a season.

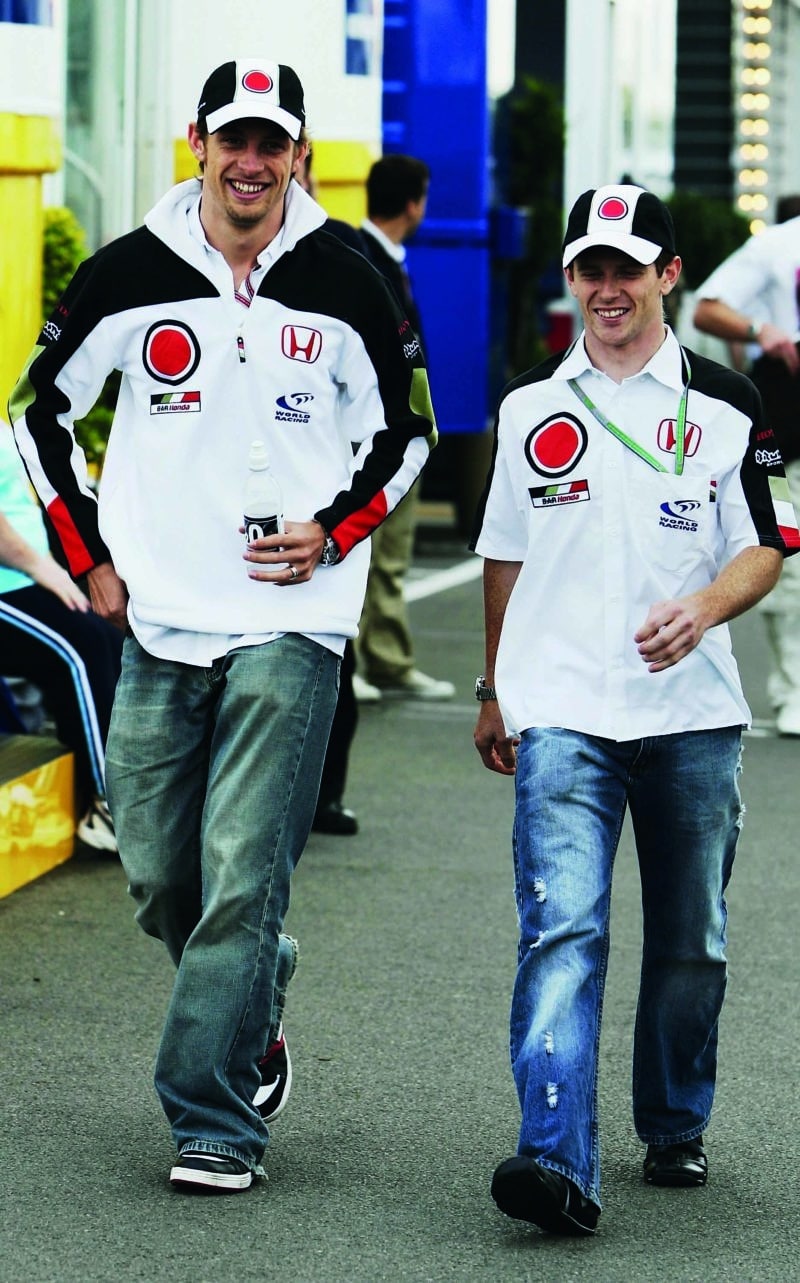

Fully paid-up ‘Brat Pack’ members Jenson Button and Anthony Davidson at the British GP, 2004

Mark Thompson/Getty Images

“I think that intense competition helped us all go on to bigger things. I remember my first ever race at Three Sisters in Wigan and Jenson was there – he’d done a handful of races so was up to speed. I remember turning up, both of us being on Novice plates, and this kid called Button demolishing everybody in the wet! We still laugh about those days when we’re together on Sky F1 duty. There’s been a few pinch-yourself moments when we look at where we’ve ended up. We also both felt it badly when we lost Dan and Justin. They were a big part of our brotherhood and it’s very emotional to think they’re not still here racing with us. That hits home pretty hard.”

Your junior single-seater career was surprisingly short. Just a full year in Formula Ford and one in F3, and you were into a Formula 1 role

AD: “It was a rapid progression. I was always successful in everything I raced, won races and the Festival in Formula Ford and won the European Cup in Formula 3. Much of the groundwork to join BAR was done without me really knowing.

“Late in 2000 my manager at the time was talking to Rick Gorne and Craig Pollock [both of BAR] as they wanted to start a young-driver programme. They wanted to see how I got on at the Festival before talking more, but my manager never told me. So after I won the Festival suddenly there was this F1 team knocking on my door wanting to sign me to this new young-driver programme. The funny thing about that is when I won the McLaren Autosport Young Driver Award that year I already had this link with Honda so I couldn’t do the prize F1 test with McLaren. But it was a fast transition. I only started in Formula Ford in late 1999, and by 2001 I was testing F1 cars for Honda.”

Mechanics make adjustments to Davidson’s Carlin Motorsport Dallara at the Formula 3 Macau Grand Prix in 2001 – also the year Davidson finished second in British F3

Antony Dickson/SCMP via Getty Images

Was it strange giving up racing to focus on Formula 1 testing?

AD: “It did feel odd, but I was so focused on getting into an F1 race seat that I fully dedicated myself to that. I thought every test was like a race audition. Trying to wow somebody with my lap times. It worked for a few drivers – David Coulthard, Damon Hill, Olivier Panis… so why shouldn’t it work for me? At least back then test drivers were actually driving.

“We’d do 15,000km [9320 miles] per year. Plus, being the reserve driver I was going to all the races as back up, which left little time for anything else.”

Your grand prix debut came with Minardi in 2002. It’s 20 years ago now, but what do you recall about that time?

AD: “That’s a funny one as it actually should’ve been Justin Wilson in that car but he was too tall for it, so the team went for the smallest driver they could find! It was a great opportunity to show myself at the top level, but we had to find £250,000 for just two races. Crazy money. Looking back it probably wasn’t the best thing. I got some experience from it, but it was jumping into the deep end a bit too much.

Minardi planned to race with Justin Wilson in the latter stages of 2002 but at 6ft 4in, he was too tall. Davidson’s chance had arrived

Clive Mason/Getty Images

“Alex Yoong hadn’t qualified for a few of the previous races, so I took his seat for Budapest and Spa. My biggest goal was just to qualify the car [which he did on both occasions, albeit at the back of the grid] and that was quite an achievement – new car, new team, unknown engine, Mark Webber as my team-mate, and I’d never been to Budapest! I’m still proud of the job I did. I was only about half-a-second off Mark in qualifying, and we had a fuel pick-up problem that cost at least four-tenths per lap.”

Your full-time F1 chance then didn’t come for five years. Was it a case of glass ceiling?

AD: “It was massively frustrating. I was desperate to race in F1. And we had some small opportunities that so nearly came off – with Williams and one with Jaguar – but those talks usually ended with a better offer from BAR that kept me where I was. I did a few races here and there – made my Le Mans debut in a Ferrari, drove a Honda Civic touring car at Macau. Those were useful experiences as they showed me there was something outside of F1. But looking back, I should’ve done more racing outside of F1 while I was a test driver. When I did get my chance with Super Aguri for 2007, I definitely felt I was race rusty for the first few grands prix. I’d been out of racing for almost six years. I had the speed, but I struggled with the racecraft. They say you shouldn’t have regrets, but that’s my biggest one.”

Canadian Grand Prix, 2007, racing with Super Aguri

Mark Thompson/Getty Images

Davidson started every F1 race in ’07

Mark Thompson/Getty Images

Mark Thompson/Getty Images

How fondly do you remember the Super Aguri days? They didn’t last long…

AD: “It was only a year and four races. But it was great to be racing, and being team-mates with [Takuma] Sato, who I knew from F3, which made it a nice environment. And at the start we had a car that was capable of fighting in the midfield, but we slowly lost ground. Annoyingly I think it was a case that I wasn’t ready for it at the start of the year but the car was, and by the time I’d got up to speed the car had gone backwards. In 2008 I was ready to hit the ground running, but the team almost folded before the first race. We eventually made it to four, but that was it and Honda was on its way out of the sport. It goes to show how much F1 relies on luck and timing as if things had been a year earlier and I’d have had that 2007 car at the start of my second year, things could have turned out differently.”

Did you come close to getting back onto the grid after that?

AD: “I did get close to something for 2009, but it was only ever as a sub or reserve. Losing Super Aguri left a big dent on the grid, so I was basically left with nothing. That was a dark time for me. I felt like everything had been taken away and my mental health suffered. My whole focus had been on F1, so when that bubble burst you just don’t know where to turn.”

Davidson was BAR Honda’s test driver at various points in the ’00s. His one race with the team would come at Malaysia in 2005 – lasting for two laps

Darren Heath/Getty Images

How did you pull yourself out of it?

AD: “I was test driver for Brawn GP, it wasn’t much, but at least I had some income. Then out of the blue Serge Saulnier of Peugeot Sport got in touch with me late in 2008 to invite me to test the 908 at Paul Ricard.

I knew nothing about LMP1 at that time, but that test made me fall in love with LMP1. There was such great camaraderie with the drivers, which you never got in F1. Peugeot had a ‘lads-going-racing’-type feel, which was so refreshing. And the car was incredible. You could drive it like an F1 car. The test went well and Peugeot came back soon after with a draft offer for 2009, but then it all went quiet. It turned out that Serge was shifted out and replaced by Olivier Quesnel, who put a blocker on the deal and signed David Brabham instead!

That car won Le Mans that year… I should’ve realised right then that Le Mans would never allow me to win it.”

But Peugeot did come back eventually?

AD: “I did Le Mans in 2009 with Aston Martin and that was brilliant. We ran as high as third at one point and led the petrol class and that put me on the map for a future at the race. Then, at the start of 2010, Peugeot got back in touch. They had been due to run Sébastien Loeb but he wanted to focus on rallying. Sven Smeets invited me to the factory for a chat, initially about a reserve driver role. As we were wandering around this photographer just appeared and they grabbed a team shirt and asked me to take a few shots in the kit, just in case.

“It was chucking it down with rain when I got back in the car. Right then my phone rang and it was Sven. He sounded really down saying, ‘Look, something’s changed,’ and I thought, ‘Oh, here we go again.’ And then he said, ‘Now if it’s OK with you, we’d like you to do everything with us. Whole season.’ I almost put my fist through the roof I was punching the air so hard. The next year we went to the Sebring 12 Hours and won.”

Airborne crash at Le Mans in 2012

Le Mans 2009 and a 13th position in the Lola-Aston Martin B09/60

Bryn Lennon/Getty Images

Davidson’s name on the Tourist Trophy

Bryn Lennon/Getty Images

Just as you’d found your calling, Peugeot pulled the plug ahead of the 2012 season.

AD: “Things were going so well. That 908 was my car, my baby. It was made for me.

I was so sad when that call came to say the programme was ending just two years into my time with them. I felt robbed again. It’s easy to feel victimised, but you learn pretty quickly that it’s just a part of the game. The drivers’ book of hard-luck stories would be pretty bloody thick!”

You’ve raced at Le Mans through a few different eras; Peugeot with the turbo diesels, Toyota with the hybrids… Did you prefer one over the other?

AD: “I loved the technology of the hybrid Toyotas. That 2016 Le Mans was incredible, barring the finish. The car had been a dream to drive before then with the hybrid engine and four-wheel drive. That was perhaps the best-balanced car I’ve ever driven. But it also has that huge sting in the tail at the finish.

“For sheer driving pleasure I reckon the 2010 Peugeot 908 trumps it. That was an absolute beast. Lower, wider, huge power and torque from the diesel: 1250nm of torque at 3000rpm and 800bhp-plus. It made you feel like a hero. I felt like Steve McQueen every time I got in it. It was so, so fast and now has that nostalgia about it.”

A move to the World Endurance Championship in 2013 with Toyota brought results; the following year Davidson won the title alongside team-mate Sébastien Buemi

Clement Marin/DPPI

Do you think your success in sports car racing changed perceptions of you after the troubles of F1?

AD: “F1 didn’t go to plan, but it was largely beyond my control. I’m my own biggest critic, yet I’m still proud of what I did in F1, but perhaps people didn’t get to see the hard racer that I am. Then when I’m scything through traffic at Le Mans in an LMP1 people could see how ruthless I could be. Annoyingly in sports cars a lot of people put my speed down to my size and weight, which was very frustrating and a bit dismissive. But I feel I’ve proved myself, and the world championship title from 2014 means so much to me. That was one of those golden years where you can’t do any wrong. We had a brilliant car in the Toyota and the minute we were confirmed champions it felt justified. The whole hard road to get there, to be a world champion. That made it all feel so worthwhile for me.”

A few years ago you said, “You don’t win Le Mans, Le Mans chooses who wins.”

AD: “Yeah, it’s a good quote that, but I stole it from Alex Wurz! He said it to me once and I thought, ‘Ahh, come on, think positive, man!’ But I’ve learned the hard way that it’s true. I feel I did everything in my power to win that race and it was never meant to be. Whether it was of my own doing or not, I’ve lost Le Mans in so many ways, and 2016 was the kicker. I once also said, ‘I know how to win Le Mans, I just haven’t done it yet,’ and I genuinely do! What I mean is that I know how to put the race together, how to set up and manage the car, what risks to take and when. I know that during that 2016 race, the way I drove… I won Le Mans that year. I don’t need the trophy or the watch to tell me I won it.

I know that during my time behind the wheel the job was done. It was the best Le Mans I’ve ever put together. I tell myself that we were the moral winners that year. Of course, history will always show it to have a very bitter ending, but at least it gave me a great story.”

The heartbreaking moment in 2016 when Davidson, Nakajima and Sébastien Buemi’s Toyota ground to a halt just three minutes from the Le Mans finish

Gerlach Delissen/Corbis via Getty Images

With the way the sport is structured now, F4, F3, F2, F1… how do you think your career would turn out if you were starting over again now?

AD: “There’s no chance I’d get anywhere. Full stop. We’d never afford it. Costs have gone up so much. Even karting now is eye-wateringly expensive. Sure, the ladder is more defined now, but are the opportunities there for anybody without a huge stack of cash? You could almost say the same about Lewis Hamilton or Jenson, too. Would they make it starting out again now? It makes you worry about the future. I feel the divide between those who can and those who can’t afford to do it is getting wider. I’m not planning to put my kids through karting.”

Why not? You’d be a great karting dad! There with the Sky-pad analysing moves…

AD: “I’d be a bloody annoying one [laughs]. Banned within seconds! I was incredibly lucky to make it through and to have enjoyed such a career. It’s been a magical journey and I’ve loved every second.”