1981 Brazilian Grand Prix race report

It was a dominant weekend for the Williams team, with Jones (above) taking 2nd and Reutemann winning

Motorsport Images

Rio in the rain!

Rio-de-Janeiro, March 29th

For most Formula One teams, the 1981 Brazilian Grand Prix represented the second event on a three race schedule which would mean them operating away from their European bases for the best part of five weeks. The World Championship season got under way with the United States (West) Grand Prix through the streets of Long Beach, California, on March 15th and then “stopped off” in Brazil on its way through to the Argentine Grand Prix, scheduled for Buenos Aires on April 12th. From a logistics point of view this operation placed an enormous burden, operating so far from home for such a long time, but the well-oiled transportation system which has been developed by the Formula One Constructors Association meant that every car which had been in Long Beach for that race was lined up in its pit garage at the Autodromo Riocentro in time for unofficial testing on the Wednesday prior to the Brazilian race.

Rene Arnoux put his Renault 8th on the starting grid

Motorsport Images

The 5.031 kilometre Rio circuit has not been used as the country’s Grand Prix venue since 1978, when Carlos Reutemann scored a very convincing start-to-finish victory at the wheel of his Ferrari 312T2 shod with Michelin tyres. In 1979 and 1980 the race took place at Sao Paulo’s spectacular Interlagos circuit, infinitely better from a racing point of view but obviously not offering the same commercial possibilities for those whose business minds have a hand in controlling the destiny of Grand Prix racing. What is more, FOCA’s boss Bernie Ecclestone told us that the race has been “signed up” to take place at the Rio Autodromo for the next two years as well, so unless we are overtaken by an Orwellian fate, 1984 will mark the return of the Brazilian Grand Prix to its “traditional” home in Sau Paulo.

Of course, in the three years which have passed since the last Brazilian Grand Prix at Rio, a lot of new drivers have arrived in the Grand Prix firmament, so this unofficial Wednesday session was welcomed by most teams. New faces included the little-known Colombian Ricardo Londono-Bridge, who had bought his place in the works Ensign team, but after he had collided with Rosberg’s Fittipaldi during one of his slow laps, Morris Nunn was informed that his new recruit would not be allowed to practice in the official sessions on Friday owing to the fact that he hadn’t provided the necessary information to FISA in order that a decision be taken as to whether he qualified for the appropriate competition licence or not. Marc Surer was thus reinstated as the car’s official driver, while another fresh face on the scene was the optimistic Jean-Pierre Jabouille who tried out his Talbot-Matra JS17 on Wednesday and decided to drive it in the official practice sessions, much to the chagrin of Jean-Pierre Jarier who was also allowed some laps in the spare and was kept on hand as the team’s reserve driver.

Further down the pit lane Colin Chapman’s interesting Lotus 88 was once again proving to be the focal point of attention, the scrutineers deferring their initial decision on the car’s eligibility until they had the chance to confer with the stewards of the meeting. Encouraged by the favourable judgement received when his Long Beach appeal was considered by ACCUS (the national sporting authority of the United States), Colin Chapman was initially optimistic in Rio when the scrutineers and stewards accepted his new car as legal and gave it a scrutineer’s label which meant that it could run during official practice. To the team’s consternation, on Friday the scrutineers reappeared and asked to examine the car once again. They asked to check that the car conformed to the regulation which states that, with tyres deflated on one side, the bodywork does not touch the ground. This they did, using sponsor’s spokesman Francois Mazet in the cockpit to simulate the weight of a racing driver. The Lotus 88 was legal. The scrutineers then rocked it backwards and forwards; it was still legal. Then they pressed up and down on the bodywork and, when the car touched the ground under these artificially contrived circumstances, it was immediately deemed illegal and excluded from further participation in the meeting. Sure enough, there had been protests from rival teams, but they were simple and straightforward, claiming that the Lotus 88 did not comply with the rules relating to aerodynamic coachwork (the Lotus 88 will be dealt with by D.S.J. once the question of the car’s conformity with the regulations has been cleared). There did not seem to be any reason why this humiliating, somewhat amateur and badly organised second examination of the car needed to take place. Perhaps the fact that most of the key race official involved spoke only Portuguese, and the FISA rules say that the English translation of their regulations is the one which must be used to adjudge disputes, contributed to the problems.

John Watson and Andrea de Cesaris qualified 15th and 20th respectively

© Motorsport Images

There were many other teams who felt that the Lotus 88 affair was throwing everybody “off the scent” of another car which was attracting more than its fair share of attention from rival teams, the Brabham BT49C with its hydro-pneumatic suspension which allows the car to sink very close to the ground at speed, well below the 6 cm. minimum clearance required when the car is leaving and arriving in the pits. All sorts of allegations were being “bandied round” including a suggestion that the car did in fact touch the ground “systematically”, which is prohibited by the rules. Brabham designer Gordon Murray stood his ground calmly, saying that he could prove that his system was legal and would do so to a FISA enquiry, if necessary, but that didn’t mean he was prepared to have all his rival team engineers crawling all over the car in the Rio paddock.

Qualifying

After all this argument, it was quite a relief to get on with timed practice which took place, in well-regulated FOCA style, on Friday and Saturday in warm sunshine. The battle for pole position raged for two days between Piquet and Reutemann, the Williams driver ending up fastest on the Friday with 1 min. 35.390 sec., only to be pipped by Piquet who squeezed in a 1 min 35.079 sec. best the following afternoon. There were more “sideways glances” from the Williams pit as the Brabham BT49C achieved this time, the feeling being “so would we if we were running with that sort of ground clearance.” But the fact of the matter was that Nelson Piquet, the man who has replaced the retired Emerson Fittipaldi in the affections of his home crowd as their national motor racing hero, was on pole position for his home Grand Prix and the entire Brabham team, from the agitated Bernie Ecclestone downwards, were grinning like Cheshire cats. They hadn’t enjoyed a trouble-free run by any means, for fuel system bothers on Piquet’s regular race car obliged him to use the spare on Friday, and his team mate Hector Rebaque had suffered a major oil leak, apparently from the clutch, before his experimental Weismann gearbox was changed for a “conventional” Brabham-modified Hewland unit on the second day. Of course, Rebaque couldn’t keep up with Piquet, qualifying the second Brabham down in eleventh place and reminding everybody that one factor that helped the Williams team to win the World Championship ahead of the Brabham team was the fact that the former has two drivers, both of whom are easily capable of winning. More than ever, the Rio race would underline just how this lack of a strong number two handicaps the Brabham team before they even start a race.

Jones was almost a full second slower than his team mate in practice, qualifying third although he was never really happy about the understeer his car seemed to be displaying on the constant radius corners of the Rio circuit. In fourth place was Riccardo Patrese, underlining the form he had displayed at Long Beach and looking very confident with his Arrows A3. That meant that the first four places on the grid were taken by Cosworth engined, FOCA-supported entries, making a nonsense of those who predicted that the highly powered turbocharged machines would run away from the 3-litre V8 opposition on Rio’s two long straights. Alain Prost was the fastest turbo-engined Renault driver, managing a 1 min. 36.670 sec. in the team’s spare car on Saturday after suffering oil system problems in the gearbox of his race car which probably contributed to the failure of fourth gear the previous day. By contrast, the normally enthusiastic Rene Arnoux, simply couldn’t “get with it” on the first day and, although on Saturday he speeded up to qualify eighth on 1 min. 37.561 sec., no sooner had he done this than he slid off the circuit into some catch fence poles which broke the left lower front suspension wishbone and rumpled the monocoque slightly. For the rest of the day he was obliged to practice in Prost’s discarded race car.

Neither Giacomelli nor Andretti had any complaints about the behaviour of their Alfa Romeo 179C V12s, although they were not running quite as quickly as they had hoped. They were, however, running quite reliably which was a pleasant contrast to 1980 and the Italian qualified sixth on 1 min. 37.283 sec. with Andretti three places further back on 1 min. 37.597 sec. In addition to Arnoux, they were split by Gilles Villeneuve’s KKK turbocharged Ferrari 126C which returned a precarious looking 1 min. 37.497 sec., seventh quickest, which was more a reflection on the very powerful engine and the driver’s lightning reflexes rather than any pleasant handling characteristics on the part of the chassis!

For this weekend the Comprex pressure-wave supercharging system was shelved and all three Ferraris appeared equipped with KKK turbocharging systems. Apart from reliability problems with the Comprex system, its installation is higher in the car than the KKK turbocharger which gives an adverse effect on the machine’s handling. A twin Comprex system is currently under development, but meanwhile both Villeneuve and Pironi concentrated on the turbocharged machines. Villeneuve’s energetic approach almost got out of hand on lap one when the cockpit fire extinguisher triggered itself as the French-Canadian was rounding the right hander before the pits. The Ferrari went bounding down the grass, crumpling the lower edges of its skirts, but otherwise remained intact. Pironi, by contrast, had persistent engine problems in his car and then spun off during Saturday morning’s untimed session, badly damaging the underside of the monocoque as well as the inlet tract for the wide 120-degree V6 engine. He was thus obliged to change to the team’s spare car, in which he qualified on 1 min. 38.565 sec., and retained this machine for the race.

Elio de Angelis in his Lotus 88 during practice – it was banned immediately afterwards

© Motorsport Images

Both de Angelis and Mansell were struggling round with their outdated Lotus 81s, the Lotus team leader frustrated that he was not going to be given a crack with the 88, and they worked hard to record tenth and thirteenth times respectively, a particularly commendable effort from Mansell whose car seemed plagued with endless brake problems as well as an electrical gremlin which was causing the engine’s rev limiter to cut in at too low a limit. others in the iddle of the grid included Rosberg’s Fittipaldi F8C, a disappointed 12th with 1 min. 37.981sec. which he managed on Friday, being unable to approach within a second of this the following day, Cheever’s Tyrrell, 14th with 1 min. 38.160 sec., and Watson’s McLaren M29F one place behind the young American. The new McLaren International NP4 did not make a reappearance for this race as it still needs to undergo some more testing, but the team was confident that it would appear for the Argentine Grand Prix two weeks later.

Surer qualified the Ensign one place ahead of Patrick Tambay’s new Theodore, which must have satisfied Mo Nunn since Theodore patron Teddy Yip severed his connection with the Walsall company to set up hos own team operation, while both Serra’s Fittipaldi and Stohr’s Arrows A3 qualified comfortably. Right at the back was Ricardo Zunino, who rented the second Tyrrell 010 to run alonside Cheever, and the second Talbot-Matra JS17. This had been finally qualified by Jarier during the last hour’s practice when the team’s management got the message, a little late in the day, that Jabouille simply was going to get into the race. By the end of the untimed session on Saturday morning, he hadn’t managed to break the 1 kin. 40 sec. barrier and was complaining that he had trouble moving from the throttle to the brake fast enough to be competitive. To many onlookers, that had been obvious from th estart of the unofficial testing on Wednesday, so why the Talbot team took so long to get the message is difficult to say. Jarier eventually managed a 1 min. 39.398 sec. best, recorded on a lap when he bounced down the grass opposite the timing line and broke the throttle linkage as he attempted to power his way out of this predicament! He then had to take over Lafitte’s original race car, which his lacklustre team leader abandoned during the morning session with major engine problems, and Jarier managed a few laps in this machine once a replacement Matra V12 was installed. Laffite, incidentally, couldn’t work out why he was so far off the pace with a 1 min. 38.263 sec. for 16th fastest, much to the frustration of the pleasant Frenchman.

Non-qualifiers included Jan Lammers in the ATS D4, Jabouille, and the two Osellas of Guerra and Gabbiani. Enzo Osella couldn’t afford to take his engineer to Brazil and then he himself succumbed to the heat and had to stay in his hotel on Saturday, leaving his two novice drivers in the company of their mechanics for the final timed session. No wonder they failed to qualify! Slowest of all was Salazar’s March 811, there being a considerable degree of behind-the-scenes aggravation following Derek Daly’s accident in Friday morning’s untimed session. A front lower wishbone mounting tore out of the side of the monocoque, depositing an irate Daly against a barrier and rendering the car hors-de-combat for the remainder of the weekend. Team chief John MacDonald had some very uncomplimentary things to say about designer Robin Herd . . . .

Race

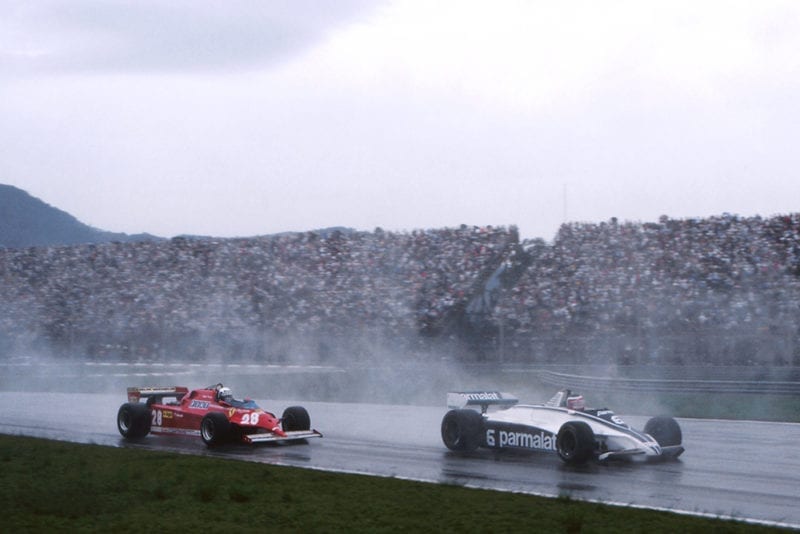

Chaos ensued at the race start

Motorsport Images

Unexpectedly, race morning dawned grey and overcast with a depressing cloud of rain hovering over the Rio area. Everybody hurriedly adjusted their cars as best they could during the half hour warm-up session on Sunday and the rain was still falling steadily as the 24 competitors took their places on the starting grid. To the complete and utter amazement of their rivals, Brabham team decided to start Piquet’s pole position BT49C on “slick” dry-weather tyres, a “tactical” decision made by race manager Alistair Caldwell in conjunction with Nelson himself. In third position Alan Jones could be seen chortling away to himself beneath his helmet, rightly convinced that this outlandish decision had destroyed any chance of Piquet being a threat to the Williams team, while in the pit lane Brabham team owner Bernie Ecclestone was almost quivering with annoyance over what he could see was a particularly stupid course of action.

Once the starting signal was given, Reutemann made a perfect start and Patrese came rocketing through ahead of Jones as they accelerated into the first right hand corner in a ball of spray. Piquet was bravely trying to hang on, but it was a totally vain ambition, and Giacomelli’s Alfa Romeo was right with them as well. But, further back, chaos had erupted on the starting grid as somebody spun Arnoux’s Renault, Andretti’s Alfa Romeo vaulted over Villeneuve’s rear wheels and Rebaque’s Brabham did the same to Andretti! The rest of the grid scrambled past on the grass and, when the mud had settled, Andretti, Arnoux and Serra were out of the contest and both Cheever and Stohr were recovering after quick spins. They chased off after the rest of the field as marshals cleared up the wreckage before the leaders came through for the first time.

Halfway round the circuit, Jones neatly outbraked Patrese for second place, so the two Williams FW07Cs completed the opening lap in “2-1” formation, the World Champion following in his number two’s wheeltracks, and Patrese was well ahead of anybody else. Giacomelli was fourth from de Angelis, Rosberg, Villeneuve, Watson, Prost, Surer, Laffite, de Cesaris and Jarier, the second Talbot-Matra driver going for all he was worth and passing cars left, right and centre!

With Piquet floundering about at the tail end of the field on his “slicks” (one wonders why the Brabham team did not call him in for wet-weather tyres), there was absolutely nothing for the Williams due to worry about, so Reutemann and Jones settled down to lap smoothly and steadily, the World Champion dropping back slightly from his team mate in order that he could run in cool air and not risk overheating his engine.

Brabham’s Hector Rebaque leads the Ferrari of Didier Pironi

© Motorsport Images

Patrese couldn’t stay with them, but the Arrows was getting away from the rest of the field with ease, and Giacomelli really had to work hard for the first few laps, eventually succumbing to de Angelis at the end of the long back straight mid-way through lap four. By lap seven the Italian V12 was coasting into the pit lane for the first of a number of pit stops to get to the bottom of an irritating misfire. The mechanics were eventually able to trace the problem to a faulty coil, but by the time his had been rectified, Giacomelli was way out of the running.

At the end of lap 10 Villeneuve headed towards the pits where he had a new nose section fitted and optimistically changed onto “slicks”, thinking that the rain would ease up further. Just as he rejoined, the rain increased in its intensity, so there was no way he was going to make up any of the ground he had lost. Nonetheless, his spirited driving kept the spectators entertained for another 15 laps before he crawled in to retire finally with major turbocharger failure. Meanwhile, Pironi had been lapping gamely on his “slicks” and was doing his best to keep out of the way of the leaders when they lapped him at the 20 lap mark. Unfortunately, he moved a little too far off the tenuous, semi-dry line as Prost’s Renault moved up alongside him, hit a puddle and shot back across the track to “T-bone” the innocent Renault. Prost’s car was pitched briefly onto two wheels as the Ferrari collided with it and in a couple of seconds, the two drivers were climbing ruefully out of their cars which had shot off the circuit into the catch fencing.

By lap 25 Jarier had forced his way up into sixth place and his Talbot-Matra was challenging Watson’s McLaren very hard. Surer had moved up to seventh, driving the Ensign neatly and tidily, while Laffite had faded to eighth and Rosberg was even further back now, troubled by understeer every time the rain eased slightly and his rear tyres could grip the track slightly better. De Cesaris had spluttered to a standstill with electrical problems right in front of the pits, Rebaque was in and out with a variety of problems which included clutch bothers and the problems which included clutch bothers and the need to clean out his Brabham’s throttle slides following a trip down the grass, and Piquet was into the pit retaining wall, Villeneuve bent his Ferrai nose section on th rear end of Prost’s Renault, trailing round at the back. Tambay’s Theodore sideswiped Stohr’s Arrows as the Frenchman lapped his rival, the Italian spinning off as a result, while Mansell was struggling round in 11th place in a car which had been damaged in a spin during the warm-up session and wasn’t handling properly.

By half distance the Williams cars were simply cruising in first and second places and Patrese was equally comfortable on his own in third spot. But a really ferocious battle was brewing up behind de Angelis’s fourth place Lotus 81, Watson fighting energetically to keep Marc Surer’s Ensign behind him while both Laffite and Jarier were also looking for a way past the Ensign, Laffite having moved ahead of his team mate once again as understeer on the near-drying track had hampered the second Talbot-Matra.

Nigel Mansell hauled his underperforming Lotus up to 11th position

© Motorsport Images

On lap 35 Watson spun off at the end of the long back straight, quickly recovering in eighth place, but Surer and the two Talbots were well ahead of him by the time he had settled back into the rhythm of the race once again. Rebaque eventually crawled in to retire with throttle and suspension problems and, as the rain came down again even harder, Laffite’s engine began to misfire and Jarier moved back in front of him on lap 47.

The Williams team by this stage had the race completely under control and, with no other car challenging them and with Jones less than seven seconds behind Reutemann, Frank Williams exercised his contractual discretion and hung out a sign to the Argentinian driver indicating that he should concede the lead to his team leader. On four occasions this sign was produced, but Reutemann continued to come round ahead of Jones and as he completed his 62nd lap the chequered flag was produced since the wet conditions had allowed two hours to elapse before the scheduled 63 laps had been completed. Reutemann thus won his third Brazilian Grand Prix by 4.43 sec. over his team leader, Jones shrugging philosophically once it was all over while remarking that he knew now that he would have to race Reutemann in future just as if his was a car from a rival team. Reutemann explained to Frank Williams that he intended handing the lead to Jones on the very last lap – but there wasn’t a last lap, so to speak!

Patrese finished a smooth and confident third while Surer displaced de Angelis with just over ten laps to go, the happy Ensign driver scoring the best ever finish for the Walsall based team and recording fastest lap in addition. De Angelis was fifth while Jarier responded to a signal from the pits and dropped back, as instructed, behind Laffite who thus took sixth place at the finish. A fuming Watson was eighth behind Jarier and the remaining runners were Rosberg, Tambay, Mansell and the crestfallen Piquet who’d stayed on “slicks” and was now two laps behind.

First placed Carlos Reutemann and Riccardo Patrese (right) take the plaudits

© Motorsport Images

It was the fourth successive 1-2 finish for the Frank Williams cars in a World Championship Grand Prix, following the two North American events at the end of the 1980 and the recent Long Beach race in California, so the team had proved its undeniable quality irrespective of the “mix up” which had caused Reutemann to win and not Jones. In these circumstances in future, Frank Williams will have to insist on an immediate response by his drivers to obligatory pit signals and one wonders whether Reutemann will be disciplined for winning the Rio race against team orders, however inadvertently he may have done it. – A.H.