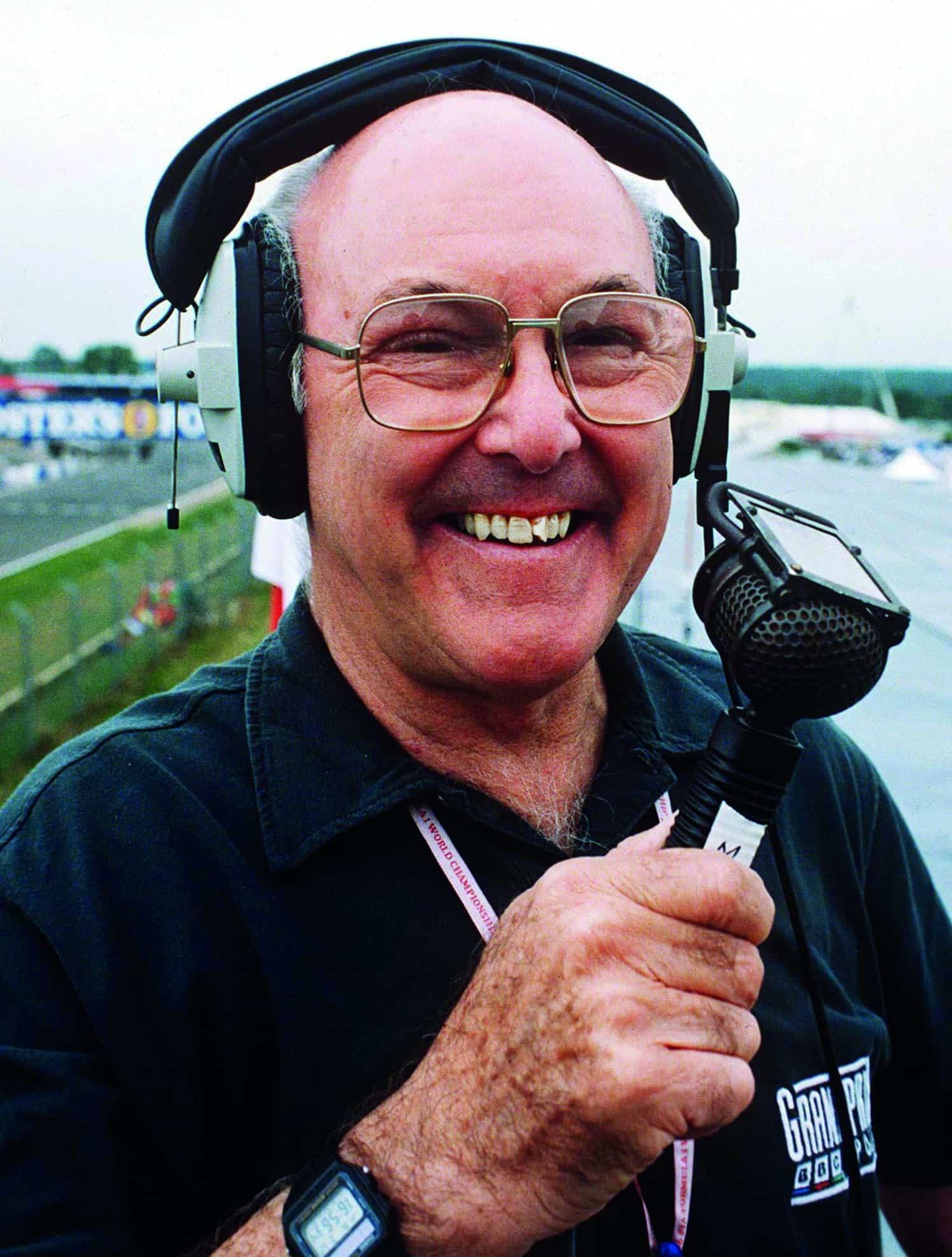

The man who brought Formula 1 into our homes

Murray Walker’s unique tones worked in perfect harmony with a revving race engine. Simon Arron bids farewell

Shutterstock

It is almost 20 years since his formal retirement as a full-time commentator, but he never really abandoned the job completely. Still working at an age that the majority simply don’t reach, Murray Walker was an institution, the like of which we might never see again. His death at 97 has left a huge hole in the fabric of motor sport – not just in the UK, but around the world.

With Murray, the passion you heard was 100% genuine – a by-product of his upbringing in a racing family.

Born in Hall Green, Birmingham, on October 10, 1923 – less than a year before Motor Sport made its bow – Murray was the son of motorcycle racer Graham Walker, winner of the 1931 Isle of Man Lightweight TT. He would go on to ride bikes at grassroots level – quite literally so, in some instances, as he competed at Brands Hatch when it was still just a field – though he enjoyed his greatest competitive successes in trials events.

It speaks volumes for his character that he was a prosperous businessman long before he became internationally famous.

He rose to the rank of captain while serving with the British Army during the Second World War and, after stepping away from military service, he went on to have a long and distinguished career within the advertising industry, initially with Dunlop. He later worked for a number of leading agencies and was credited with several slogans that became part of British TV’s lexicon during the 1960s and 1970s: ‘Trill makes budgies bounce with health’, for instance, or ‘Opal Fruits, made to make your mouth water’.

“Murray had a way of making everyone feel like a friend”

His commentary career evolved in parallel, albeit very much as an extracurricular activity.

He first picked up a microphone at Shelsley Walsh in 1948 and later that year took his mother’s Morris Minor to Silverstone to watch the RAC International Grand Prix at the circuit’s inaugural meeting. Little did he realise that, seven months hence, he’d be back at the venue, this time sitting in the primitive commentary box at Stowe. “I saw John Bolster have an absolutely enormous accident in his ERA,” he recalled, “and felt certain he was probably dead. I wasn’t quite sure what to say, so just blurted out something like, ‘And Bolster has gone off.’” Bolster recovered and later became technical editor of Autosport.

He obtained his first regular commentary job during the 1950s, working alongside his father to provide radio reports at the Isle of Man TT and assuming a lead role after the latter’s death in 1962. Wider recognition was forthcoming over the next two decades, when he covered rallycross and motorcycle scrambling for TV sports shows on Saturday afternoons. By day, though, he remained an advertising executive – as he would until he was almost 60.

It was only in 1978 that the BBC began to show recorded highlights from every grand prix and Walker was chosen as lead commentator, a role he maintained when full live race coverage came on stream during the early 1980s. He remained in situ until late 2001, switching between BBC and ITV as the contract changed hands. And long after his ‘retirement’, he continued doing documentary work for BBC and Channel 4 into the late 2010s. At the Nürburgring in 2007, aged 83, he stood in as lead commentator for BBC Radio 5 Live during the Grand Prix of Europe. Yes, there were occasional gaffes throughout his career, but they made up a tiny percentage of his output. And to many listeners or viewers, they became an endearing trait. As he often put it, “I don’t make mistakes. I make prophecies that immediately turn out to be wrong.”

Along the way, he forged strong partnerships with several former racers, including James Hunt, Jonathan Palmer and Martin Brundle. Walker was happy to admit that he hadn’t initially wanted to share the booth with Hunt, but despite their contrasting personalities the chemistry worked – even if he did once come close to punching the 1976 world champion, who had just snatched their shared microphone from his grasp. A stern glance from producer Mark Wilkin helped restore equilibrium.

Walker’s popularity blossomed thanks to his effervescent manner and warm personality. It didn’t much matter whether you were a multiple champion, an aspiring racer, a cub reporter or an autograph hunter, he saw no distinctions and would always make time.

I was fortunate to collaborate with him on various projects, including Murray Walker’s Grand Prix Year, an F1 annual I edited for several years. On a number of occasions during this period I’d come home to hear my wife chatting happily on the phone and she’d give me a wave before continuing her conversation. Ten minutes later she’d bring me the phone, “It’s actually for you, it’s Murray…” He had a way of making everybody feel like a friend.

I also had the privilege of lap-charting for him during the Formula Ford Festival at Brands Hatch in the 1980s. As well as scribbling notes that might usefully be weaved into his commentary, I had to duck frequently to avoid Murray’s arms as he jumped around the box, pointing out things to an audience that couldn’t see him. But that was the norm, a man totally absorbed in the task at hand and trying to make the racing sound exciting because he found it exciting.

And whenever you phoned to pick his brains about bygone races he’d seen first-hand, just as you started to wind down the conversation he’d pick it up again and turn the tables, throwing in questions about a feature he’d read in this magazine or elsewhere, asking what you thought about Team X signing Driver Y, or perhaps the latest F1 regulations. His enthusiasm was infectious.

I’m sad that I’ll no longer be able to make such calls, but above all this should be a time to celebrate a life lived to the full – and then some. Thank you, Murray