Page 4

The month in MOTOR SPORT

SEPTEMBER 15:Peugeot confirms that it will enter F1 in 1994, but declines to nominate a partner for the time being.…

SEPTEMBER 15:Peugeot confirms that it will enter F1 in 1994, but declines to nominate a partner for the time being.…

Follow the French In our summary of the final two European 1 Formula 3000 races of the season (see page…

The Grand Prix Mechanics' Charitable Trust day at Silverstone on October 6, organised by Jackie Stewart, was adjudged a huge…

Rodger Freeth Fatal accidents are fortunately rare in rallying, which makes it all the more difficult to accept them when…

Whatever was wrong with Michael Schumacher's race car, swapping to the spare brought him an unexpected Portuguese triumph Michael Schumacher…

It was a cool, dry day, Tuesday July 19 1983. Donington Park was bathed in weak sun, and conditions were…

Appreciation of a new book dedicated to Britain's seven F1 world champions Following the concept of its previous publication, Racers…

Alain Prost's retirement leaves Ayrton Senna a clear road We used to have a sort of natural culling of drivers.…

In the summer, we carried a letter proposing the use of the title 'Scottish Grand Prix' to bring a second…

Juha Kankkunen's victory delighted Toyota, which became the first Japanese manufacturer to take the World Championship, but celebrations were overshadowed…

Whilst Colin McRae was spending much of his mid-year time on the other side of the world, the other rallying…

As an aid to spectators, we have included details of all special stages on the rally, even those which are…

From November 21-24 Britain's biggest sporting event will take place. The RAC Rally regularly attracts more on-the-spot watchers than the…

French Connection Going into the final two European Formula 3000 Championship rounds, both of them in his native France, Olivier…

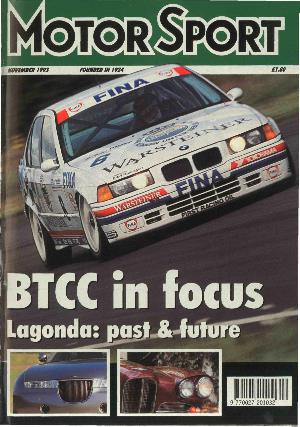

The BMWs of Joachim Winkelhock and Steve Soper would squat down and catapult off the line as the lights flashed…

Yokohama has ruled the roost in the BTCC tyre war since Robb Gravett's dominant 1990 season, but finished this year…

Nigel Mansell's victory at Nazareth Speedway having turned the IndyCar finale at Laguna Seca into something of an anti-climax, it…

Life can be pretty tough for Britons touring northern Europe in the 1990s. I mean, in August you could actually…

It has long been my ambition to produce a car which would be equally suitable to drive or to be…

The last Lagonda was produced in May 1990, but the Vignale seen at the Geneva Show last March was a…

Jochen Mass remembers how his only F1 win came at one of the world championship's true low points in this month's edition

Live updates from pre-season testing ahead of the 2023 F1 season, including full testing schedule, driver lineups and the latest updates from the pitwall

Everyone knows Honda’s RC213V is no armchair ride. But why? Best man to ask is Takeo Yokoyama, HRC’s technical manager who works with Marc Márquez, Cal Crutchlow and now Alex…

Who is Phillip Island winner Raul Fernández and why have his four seasons in MotoGP been so complicated?