Jochen Rindt: Born to be king

Fearless throughout his short life, 1970 F1 world champion Jochen Rindt was the embodiment of the fighting spirit and became a folk hero to many

Nerves of steel were needed to face the rain and poor visibility at the washout 1968 German Grand Prix. Rindt managed a podium finish

Getty

Half a century after his untimely death at the Italian Grand Prix meant he became Formula 1’s only posthumous world champion, Jochen Rindt’s influence smoulders still in a certain quarter of the paddock.

There, at Red Bull-Honda, his old friend and partner-in-crime Dr Helmut Marko remains, for ambitious up and coming race drivers, one of the most important yet fearsome figures. Often when a young man has been less favoured than a team-mate, or has been dropped for being too slow or insufficiently committed, frustrated observers have wailed, “He can’t do that!”

But those who expect leniency and an understanding shoulder for a young man to cry on understand nothing about the school of hard knocks in which Marko was educated. And Rindt was its leading pupil.

His parents Karl Rindt and Dr Ilse Martinowitz ran Klein & Rindt, the family spice mill in Mainz, and were a modern couple. Ilse was a liberated woman who smoked, skied and drove cars. Her son inherited her rebellious genes. Karl and Ilse did not live to see these develop, however. In July 1943 they were in Hamburg when the RAF and USAAF unleashed the firestorm bombing raid Operation Gomorrah. Rindt was later raised in Graz by his maternal grandparents Dr Hugo and Gisa Martinowitz, and would fervently regard himself as Austrian, not German.

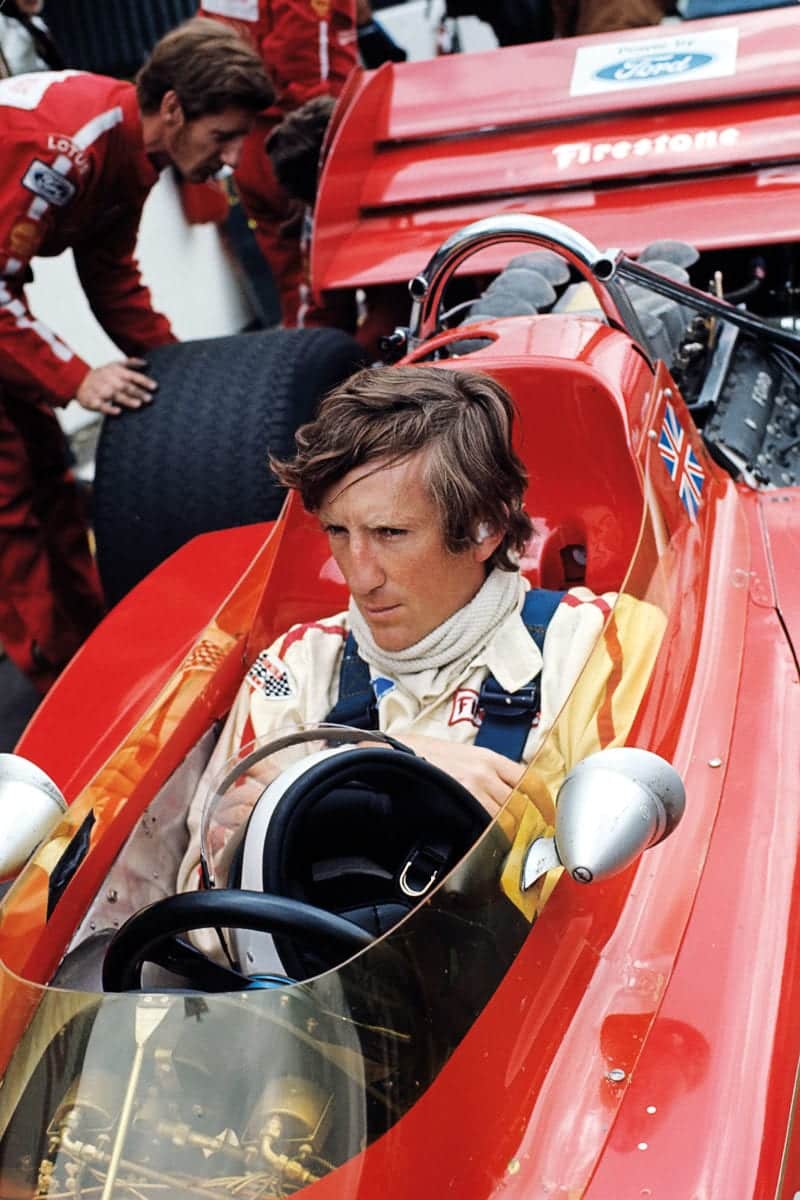

Driving a Lotus 72 in the 1970 French Grand Prix, a surly Rindt was victorious despite the pain of a stomach ulcer aggravated by his relentless smoking and the g-forces of the circuit

Hugo was a solicitor and the young Rindt lived comfortably. He was a happy and popular child but his fierce independence and headstrong character got him into trouble during his early school years, where he hung out with a bunch of fellow moped riders who did all the things one would expect of teenage boys.

Of his friends, Andy Zahlbruckner’s father was a doctor, Stefan Pachanek would become a six-day trials rider and Helmut Reininghaus’ family owned a brewery. But Rindt’s soul brother was Marko, an electrical dealer’s son. “We were in school at Graz when we got our Wombats – motorcycles,” Marko recalls. “Whatever we did on them was competitive.”

Rindt borrowed his from a policeman who lodged with his grandparents, and often broke bones riding it.

He and Marko were both expelled from the Pestalozzi School in Graz. “Let’s put it this way,” Marko explains, “if we left, they would give us a positive report. If not, we wouldn’t make it. So it was an attractive offer. We were a wild age and we really didn’t fit in this system of nice boys. So we went to a boarding school called Bad Aussee in the mountains, and that was a really crazy time because whatever you had to do, you had to organise yourself. Climbing out of the windows during the night… Jochen was a very good skier but one day he broke his thigh. It was the second time he had broken that leg so the healing took longer.”

Rindt eventually inherited the spice mill, but had to wait until he turned 21 before he could access any money. He persuaded his grandfather to let him use an ancient Volkswagen to get to and from school, having learned to drive while living near Goodwood in Sussex, where he had been sent after being thrown out of another school. The car smelt of pepper. He drove it without a licence for 18 months, and then got caught the day before he was eligible for one. Yet again, the patient Dr Martinowitz stepped in on his behalf.

“The old Beetle had no synchronisation on the gears and the throttle was a little button,” Marko laughs. “The brakes were operated by cables. Jochen quickly found a solution, telling his grandfather that we had someone who had a licence in our class, so we were saving him money because he could send home the chauffeur. You know of course how this story ends!

Rindt, right, with half-brother Uwe, in the Austrian mountains, 1955/56

“We had a car, no licence and we managed to go nearly every weekend to Graz where we had our parties. The system was like this… Everybody gets a drive but only as long as he doesn’t make a mistake. A mistake means he was not on the limit, so he was judged by all the others. And let’s say some wild driving started! To survive this era was already an achievement. It was unbelievable! There are so many stories.”

In time, Rindt acquired a Simca Aronde and when Marko decided his Steyr-Puch was too slow he took to ‘borrowing’ his father’s Chevrolet for their nocturnal adventures. Often they would try to persuade unsuspecting civilians that the roads between Graz and Bruck were closed for an ‘official test’.

The agreement was that Marko could only attempt to pass Rindt in corners, as the Chevrolet had such a clear power advantage on the straights, but one night events came to a sticky end. While trying to overtake, Marko encountered a truck and immediate action was needed to avoid a collision. The Chevrolet ended up teetering on the edge of a precipice, down which it slithered as Marko tried single-handedly to rescue the situation as his friends jeered and laughed.

This is where Marko’s legendary tough approach to young drivers and refusal to wet-nurse them was forged. “We belonged to the same gang but were not considerate to one another,” he explains. “Being over-sensitive was regarded as a weakness, so if you got into trouble you were on your own. Nobody dreamt of asking for help.”

Helmut Marko and Rindt were close friends from school days. Both were fans of German driver Wolfgang von Trips

Rindt took up racing almost by accident. “We had our final examination,” Marko recalls. “Jochen was 19, I was 18, and Jochen said now he wants to go racing. He made a deal with his grandfather and started rallying in airfield races because we didn’t have a permanent circuit in Austria at this time.”

In August 1961 they went to the German Grand Prix together in Rindt’s Simca. Marko laughs as he remembers the trip. “Jochen forgot his wallet and by the time we reached Mainz we were out of fuel and out of cash. So without batting an eyelid, Jochen knocked on the door at Klein & Rindt. The night porter was unimpressed, but Jochen insisted that he rouse a secretary, who gave us some money to continue.

“That was a trip of 14 hours or so, and at that time the roads were like a racetrack, and we enjoyed that,” says Marko. “So when we arrived we went to the Schwalbenschwanz [track section], where we laid on the grass with a blanket and fell asleep. Not even the noise of the Ferraris could wake us up. So that was our first contact with Formula 1.”

They had gone to see Wolfgang von Trips, the young German aristocrat known fondly as ‘Taffy’. He and title rival Phil Hill were thrashed that weekend by Stirling Moss in Rob Walker’s Lotus. Marko says the other point of note that weekend was that Rindt confided in him his ambition to race in F1. “We were hanging on the fences and Jochen told me, ‘I want to do that.’ So I said, ‘Okay,’ like somebody was talking in a bar in the evening. But there it was, the first time from him, very clear, ‘I want to do that.’”

Rindt had the swagger to carry off wearing a full-length fur coat, as few people could

It was fitting that it was Trips who inspired Rindt. The German was a snappy dresser, who often drove faster than was wise. He was the perfect role model for a young man who liked wearing red jumpers and pink trousers.

Rindt and Marko were on their way back to Graz from a hill climb the day Trips died at Monza. “At that time there was a light writing on a building, which gave you all the headlines, and it was evening otherwise we wouldn’t have seen it. And there was the news about Trips’ death at Monza. That was where we learned about it.”

As Rindt swiftly ascended the racing ladder, Marko was impressed and inspired. “He immediately was fast and he got some support from the local dealer in the second year when he got an Alfa Romeo, and with that he won nearly everything. He was always looking for the competition and when he saw that there was nothing which was anywhere near him in Austria, he went with the Alfa Romeo to Italy and some European races.

“When he got a Formula 2 car he quickly found out again that there was no opposition for him. He had to go to England. Being an Austrian, our English was mainly from schooling, a very low level, but he made his decision and went, as you say, to the place of the lions. And that was brave. That was typical of Jochen’s character. Where is the biggest opposition? I want to beat them all. That was his attitude.

Champagne for Rindt and wife Nina after setting a lap record during practice at Brands Hatch in 1970

“Some mistook that for arrogance, but he was just confident. I never would say he was arrogant. Through the language problem, maybe it sounded a little bit like that, but he never was. He was faithful and you could rely on him, handshake quality and all that.”

The pair remained close as Rindt’s career quickly burgeoned. After his studies, Marko established himself as a competent racer, winning Le Mans in 1971 and was racing hard for BRM in the French GP at Clermont-Ferrand in 1972 against Emerson Fittipaldi and Ronnie Peterson when he was blinded in one eye by a stone thrown up as they fought over fourth place. “Personally, I would never have done what I did, had the confidence to go into international racing, without Jochen,” he admits. “But I saw what he did so I said, ‘Oh good, I’ll do this too.’”

Had he lived, Rindt’s influence would also have been felt off the track in F1, as his close friend Bernie Ecclestone’s control developed in the ’70s. They had met in 1965 when Rindt was going to drive for Cooper in F1, after his sensational arrival in European F2 in 1964, thanks to Bernie’s friendship with team boss and former racer Roy Salvadori. Rindt and Salvadori didn’t get on, but Ecclestone and Rindt were on good terms.

Rindt moved to Lotus in 1969 but had voiced his concerns about its safety record

“I have no idea why,” Ecclestone laughs. “We just clicked. I used to look after everything financially for him, except we ran the Lotus F2 team together as partners. I used to do the deals and Jochen used to collect the money and drive the car. He had a key to my house and would come back maybe at three o’clock. Knock on the bedroom door. I’d go down to the kitchen and play gin rummy.” Again, he chuckles at the thought. They would play all the time, in airports, on aeroplanes, in the paddock. “It was for money and I think we were about as good as one another.”

Ecclestone enjoyed Rindt’s honest, outspoken manner. “He’d call a spade a spade,” he says. “I could trust him with anything, you know. He was thoroughly trustworthy. To me, that’s important.”

History remembers Ecclestone as Rindt’s manager, a point he qualifies. “I never managed him, but I always managed him. Nothing was ever official, we were just mates. When he had the contract with Lotus, I did the deal for him. In those days that was the best deal there was.”

The last race of 1965 was in Mexico, with Rindt driving for a struggling Cooper

Rindt’s first year with Colin Chapman was fraught. Their relationship never had the warmth of the Lotus chief’s with Jim Clark, and Rindt spoke his mind. He was furious after rear-wing failures caused him and team-mate Graham Hill to crash in the 1969 Spanish GP, and wrote to the specialist media, which incensed Chapman.

Ecclestone grins at another recollection. “At Zandvoort they were not happy. Jochen didn’t want to use the four-wheel-drive Lotus 63. Colin used to phone me in my room, and he would say, ‘Tell Jochen this.’ I would then ring Jochen and say, ‘Colin says this.’ The relationship improved a little after Jochen and Colin had a long talk at the Nürburgring.

“Colin was okay,” Ecclestone says. “Jochen only argued with him about the way the cars were built, their strength and frailty. I know they spoke at length at the Nürburgring and things quietened down a bit. Jochen was that confident in himself that he didn’t have to get angry.

“He always knew that if he was driving for Lotus, the chance of having a serious shunt was a lot more than if he went back to Jack [Brabham] for 1970. I suppose in a way I wanted to put him off, but he had a strong desire to win the championship and he thought that was the best chance.”

The road to the 1970 title really began in Monaco, where Rindt eventually won in stunning style, taking the lead on the last lap after Jack Brabham locked his wheels and skidded on a bend. But there had been drama even before the race.

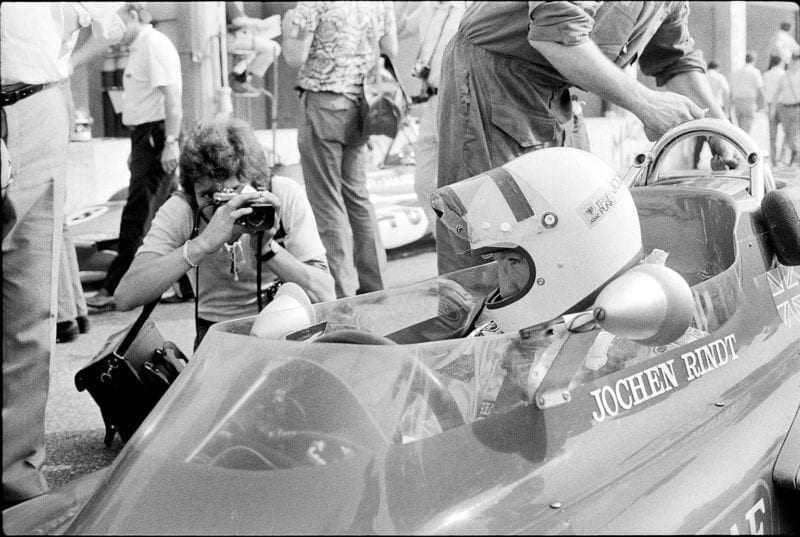

Practice session at Monza, 1970. This is one of the final pictures taken of Rindt

Getty

“We were sitting on the pit counter with Colin,” Ecclestone recalls. “Here is Jochen in his racing suit, everyone knows who he is. And this policeman started on him, so Jochen took his armband out of the front of his overalls and put it round his ankle. When the policeman grabbed his leg and made as if to remove it, Jochen kicked him in the face. So we all hopped over to the car, and Jochen, me, Colin and all the guys strong-armed the police out of the way. That’s how it used to be.

“I told Jochen not to come into the pits unless he was on foot, and I admit that for a while he was asleep in that race. But then he woke up.”

That victory came in the Lotus 49C, but from Francorchamps on, Jochen had the revised 72, and won four races in a row – the Dutch, French, British and German grands prix. Unknowingly, with his victory at Hockenheim, he had done enough to cement a title he would never live to see.

The death of his close friend Piers Courage in the Dutch GP had made him think of stopping. “It was a bad time,” Ecclestone says. “We brought Sally [Courage] and Nina [Jochen’s wife] back in the plane to London, and he was just terribly upset about the whole thing. He was talking about quitting immediately afterwards, but I don’t think he would ever have stopped.”

The front row of the 1969 Dutch GP found Rindt alongside Jackie Stewart and Graham Hill

And then came the Italian Grand Prix. “The night before we went to Monza, I’d gone to Jochen’s house and we were going to drive down with Nina,” Ecclestone says. “We had a guy we were trying to get to do some sponsorship. We got in the sauna, and the guy didn’t want to be in there. It was getting hotter and hotter, and we’d ladle some more water on. We were talking to this guy, ‘Can we do a deal?’ ‘Yes, yes.’ ‘Okay, shake hands.’ The guy would have given us his factory just to leave. The next day we jumped in the car and headed to Monza, and we laughed about that. We rarely had the chance to be as relaxed as we were then.”

On the Saturday afternoon during practice, Jochen crashed his wingless Lotus approaching the Parabolica curve at 180mph. Its wedge nose dug under the Armco and as the arresting force torqued the car anticlockwise, Jochen submarined in the cockpit (he hated doing up the lap belts).

“Somebody said there’d been an accident, so I ran to the corner,” Ecclestone says. “It’s not a nice thing, but I remember carrying his helmet back. I didn’t see him; by the time I’d got there, he’d left. They told me where, so I jumped in the car and went to the hospital. I was informed by people there that he’d been in the medical centre and they’d tried to revive him. He wasn’t dead for sure when they first put him in the ambulance. Whether he was dead at the scene or died on the journey, I don’t know. He was certainly dead when I saw him in the hospital.”

Rindt with friend Bernie Ecclestone before the 1970 British Grand Prix, Brands Hatch

Ecclestone helped to safeguard Chapman, whom the authorities threatened to arrest. “Somebody had to do something,” he says. “The shock at the time doesn’t hurt you as much as afterwards, because there’s so much going on, you have to do so much… You just get swept along.”

He had discovered this with Stuart Lewis-Evans’ death following an accident at the Morocco GP in 1958, and adds quietly: “They were both close with me, those guys. That’s when I decided that maybe I would take a bit of a break. I tried to distance myself from getting close to drivers after that, but it’s difficult when you are with nice people and they are friends. It’s hard. All my drivers, I’ve been good friends with. It’s hard to distance yourself, much as perhaps you’d want to. I was lucky to know good people like Stuart, Jochen, Pedro Rodríguez, Carlos Pace, Ayrton too. Friends, very good friends.”

He pauses again, and adds, “Thank God it doesn’t happen now.”

As a driver, Ecclestone thought Rindt was the best of his era. “Without any doubt, he was in the top five guys that have been around. As quick as Jimmy [Clark], sure. He never rammed it down people’s throats, but in himself he knew there wasn’t anybody out there that he wouldn’t be able to blow away. I spoke to a doctor once. You know when a bird can swoop and pick a fish out of water? He said that Jochen’s eyesight was exactly the same. I wish he was around now, same age as he was then. He’d give these guys something to think about, I’ll tell you!”

A blistering battle between Rindt and Jackie Stewart in the 1969 British GP ended prematurely after JYS warned his friend Jochen of his broken wing endplate

Grand Prix Photo