The Toyota Corolla - One of the Best Japanese Family Cars

On the fairly safe assumption that many people Will soon be shopping for more economical cars, we decided to look at a few more of these before the year ended.…

“I’d just come to grips with Emerson Fittipaldi when James arrived at McLaren. He was younger than me but he’d matured a lot, won a grand prix, and he was the British driver in a British team, so it wasn’t easy. When he was within sight of the championship in ’76 he became very intense and hyped up, so uptight that he used to pee up against the fence in front of the spectators before the start.

“There was always a mutual respect between us. I could match him sometimes but he trusted me to back him up at the last race at Fuji in 1976. One story, I think, typifies both James and the times in which we lived. At the Spanish GP in ’76 we went to lunch with King Juan Carlos and he asked if we’d like to see the cheetahs he kept. James’s girlfriend ‘Hottie’ [Jane Birbeck] went in with them first and a cheetah clawed at her skirt to reveal an early version of a string thong. James called out, ‘Bet you’re glad you’re wearing your knickers today.’ The King laughed but Queen Sophia was not so amused. “James was wild. He never calmed down completely and I think there was a reckless streak that came between him and his well-being. As a driver he was masterful and brave. When he came to McLaren from Hesketh he was used to a one-car team, getting his own way, so he covered his cards, never gave anything away. I liked him. He was fun but your team-mate is your enemy. If he’s quicker in the same car there’s no excuses left.”

“James was not only a quick racing driver, he was also tough; extremely competitive. The first win is always the best and the International Trophy at Silverstone in 1974 remains a great memory. He was on pole by a mile then he dropped right down the field when the gear lever broke on the first lap. Then he came back, passing everyone, and taking Ronnie Peterson with two wheels on the grass at Woodcote to win.

“The only contract we ever had with him was signed on the back of a beer mat in Belgium when we first met him at Chimay. Later on, when he was testing the Wolf at Silverstone, he came to see us at Easton Neston and he wasn’t a happy man. Far from being all bravado, he’d become analytical, setting boundaries for himself within which he’d feel safe. I think he had begun to worry about the danger.

“James was a sportsman at heart – he’d played cricket for his school, squash for his county, there was nothing he wasn’t good at. If he’d been born 20 years earlier he would have been a fighter pilot. There would have been a lot of black crosses on the side of his Spitfire.

“He had no time for the celebrity thing. It really didn’t interest him. One of his great strengths was that he came from a big family who weren’t driven to express their ambition through their children – they were terrifically supportive but not in a pushy way – and that gave him a solid foundation in his life and in his racing.”

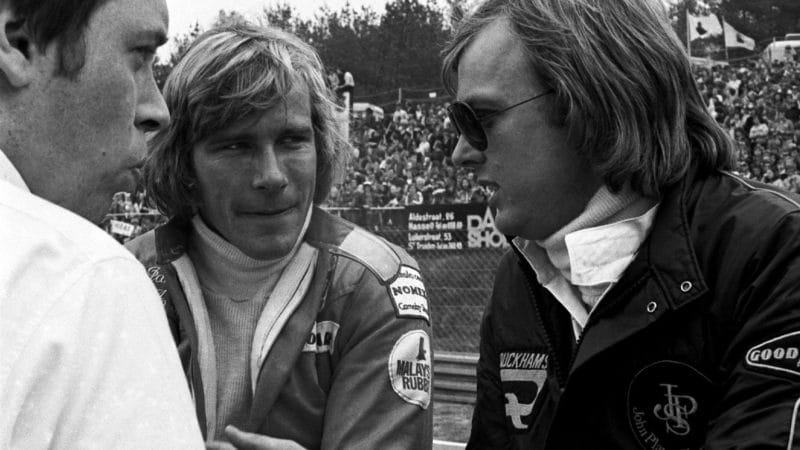

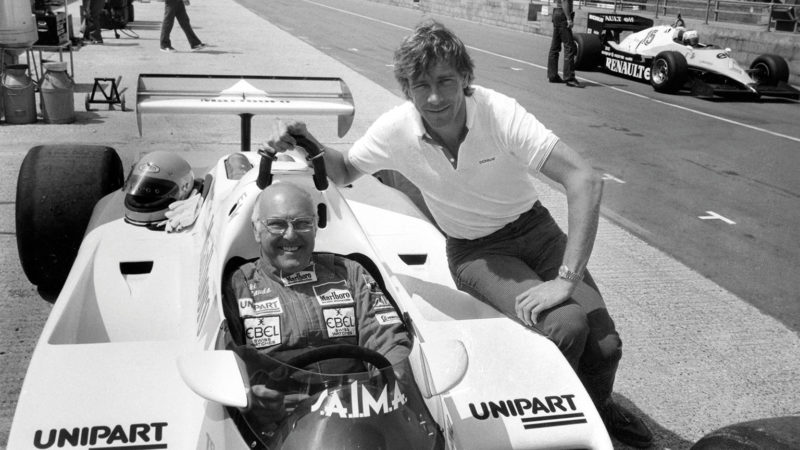

John Watson, driving for Penske in 1976, trails Hunt – on his 29th birthday – at Zandvoort

“James was a fairly hyper personality, well educated, intelligent, from a good family, and he knew how to behave although he certainly disproved that. A lovely guy, good to be around, but he lost his rag easily. I thought of him as an athlete rather than a racing driver – exceptionally competitive.

“When the Hesketh team rocked up in Monaco in ’73 it was a travelling charabanc and the legend that is James began with a great performance in a March. They captured the public imagination. It looked frivolous but James was driving as hard as ever and in ’75 he won the Dutch Grand Prix, an outstanding achievement.

“At McLaren Teddy Mayer found the trigger that fired James to win. He’d wind James up. He was already hyper, but his focus as an athlete was solely on winning. He was never interested in the engineering, the technical side of the sport.

“In ’76 he won six races. His world championship was helped in part by Niki’s accident; just a single point in it at the end. They were different people but friends. By ’78 Marlboro was thinking, ‘Is this guy at the races?’ His behaviour out of the cockpit was too much and he was released.

“At Wolf James realised the car was not a winner and he didn’t enjoy being a midfield runner. He knew that the longer he raced in an uncompetitive car the more likely he was to die and James decided he didn’t want to die in a racing car when he wasn’t winning. It was a typically spontaneous decision. “There was space for men like him in the sport back then. The fans liked that. Sports need these kind of people. Today’s F1 fans may not know him but James is a part of motor racing history. That’s why you’re still writing about him.”

Hunt and Lotus’s Ronnie Peterson at Zolder in 1975. Hunt was a month away from a first F1 win

“I bumped into James quite by chance. We were having a pee next to each other in the rather basic loos in the paddock at Chimay. I asked him what he was up to. He told me he’d just been fired by March, so I asked him if he’d like to drive for our Hesketh Formula 3 team. His response was, ‘Do I have a choice?’

“So we ran as a two-car team with me still racing the other car. We wrote both cars off at Brands at the end of the year so James persuaded us to do F2 and he did rather well. We knew we had somebody pretty special so we took him to South America for the winter series. “Back in England we got a Surtees which James then wrote off in qualifying at Pau, so we went to lunch with Max Mosley who agreed to rent us a March to do Formula 1.

“James was always the driving force. He’d really pushed us to do F2, and now he’d started motivating us to get a Formula 1 team organised. He helped us persuade Harvey Postlethwaite to join, and Nigel Stroud from March, which didn’t best please Max Mosley but James wasn’t worried about all that.

“James was fun, brave and quick, and for us he was the right man at the right time for a team like Hesketh. Well, there wasn’t really another team like Hesketh and we had some very good times together.”

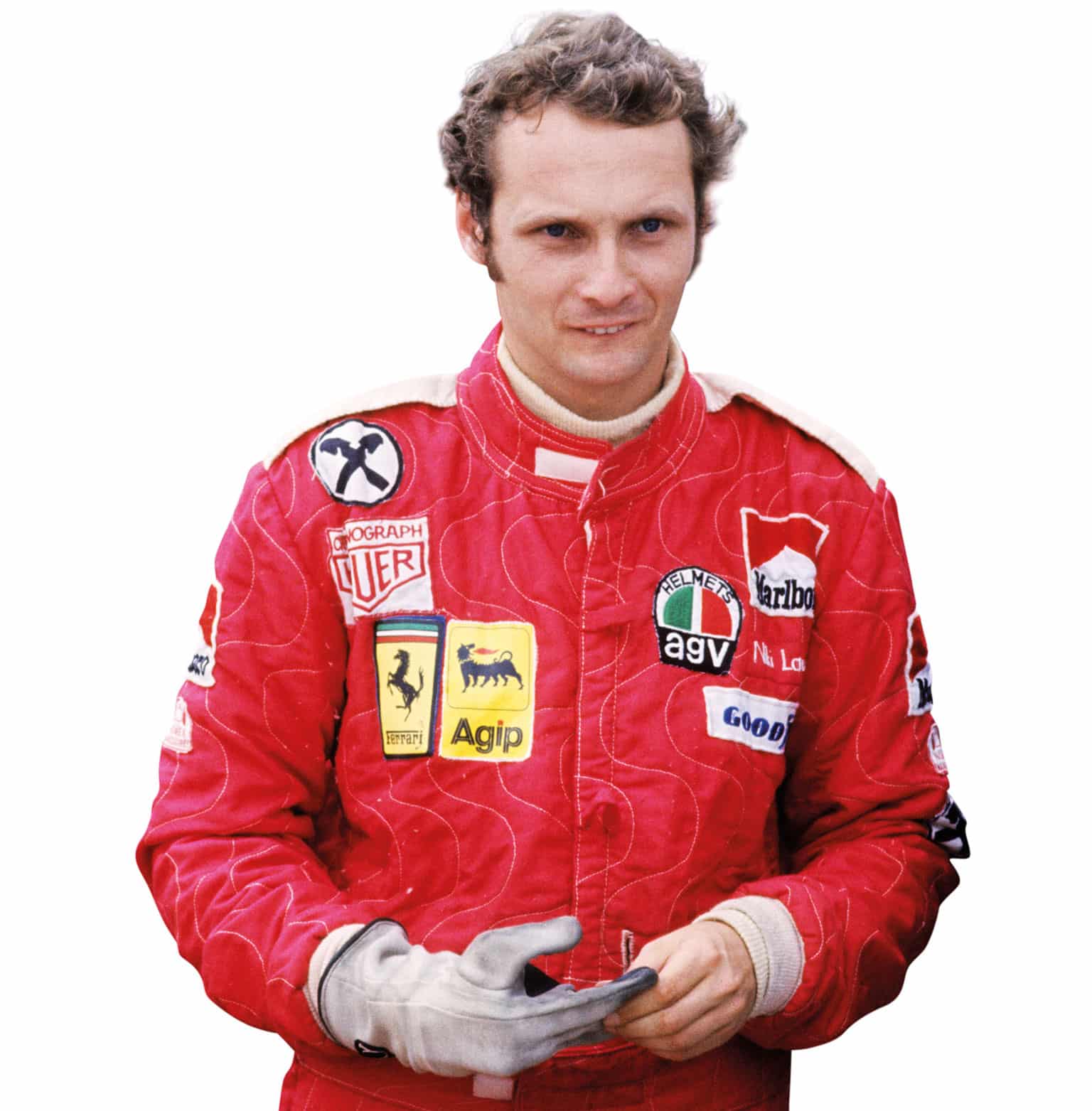

Emerson Fittipaldi had much respect for Hunt’s bravery in ’76

“James Hunt was a great driver, quick and brave. We had some good battles in 1975. I remember it took a few laps to pass him when we finished first and second in Argentina. When I left McLaren at the end of that year I knew the M23 would be an even better, even faster car in ’76 because of all the development work we’d done in testing towards the end of the ’75 season.

“James won six races and the world championship in that car but I never resented that success because he raced superbly under a lot of pressure in the fight with Niki Lauda. The last race in Japan, most of us thought it was too dangerous, too much water on the track. James stayed out there. You could say he was brave, but that was his chance to win the championship. I was pleased for him. I liked him a lot – he was fun, a bit different, you know.

“When he came to Formula 1 with Hesketh they didn’t have a smart motorhome in the paddock so James used to ask me, ‘Can I come to McLaren and use the facilities?’ It’s all nearly 50 years ago but people still talk about him.”

“We’d known each other, and raced each other, since Formula 3 in Europe. James really got his act together at McLaren in 1976 – with the car and with his own performance. He was an outstanding driver, very quick, but there were times when the car was not as good as he would have liked.

“At the beginning of the ’76 season I could beat him with the Ferrari quite easily, and he had no real chance because, at that stage, the McLaren was really not good enough.

“In the second part of the season, when I came back after the crash at the Nürburgring, the McLaren was a lot faster and he started winning. He was very difficult to beat when the car was right and he just got stronger as the season went on. That’s why he was world champion in the end.

“We were fighting each other for the world championship but our relationship was always good; normal I would say. The more competitive it got, the less we talked to each other, because we were so busy trying to beat each other. You could always trust him on the track if you went alongside him into a corner, but he was very quick too and that was the problem.”

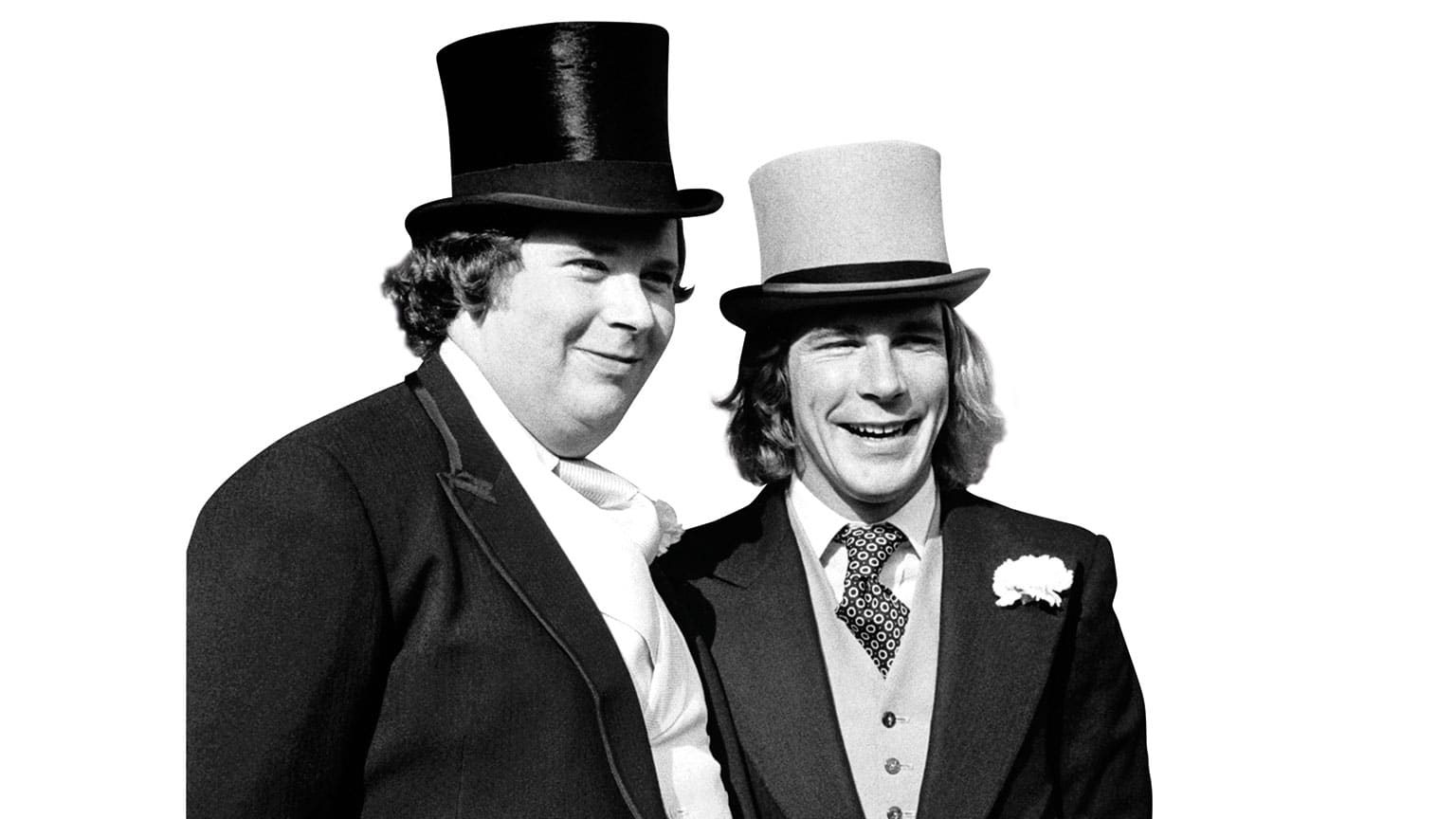

“It’s go, go, go!” Murray Walker and Hunt were commentary gold

“When the BBC told me James Hunt was to be my co-commentator my immediate reaction was one of dismay because I didn’t have the highest opinion of him as a person. There was never anything nasty between us. I did most of the talking and we got along, rubbed the rough edges off each other. I was old enough to be his father and there were aspects of his life, outside the car, that I didn’t approve of.

“He was a man of moods, had a terrible temper, but he could also be utterly charming. We made a good combination because James was so knowledgeable and outspoken. I only had to say something complimentary about Riccardo Patrese, who James blamed for the death of Ronnie Peterson at Monza, and he would pour bile on poor Patrese.

“We did the South African Grand Prix from a studio in Shepherd’s Bush and it was important not to say anything that made the viewers realise we weren’t actually there – but James had very strong views on apartheid and he started banging on about it during the race. Our producer handed him a note which said ‘Talk about the race’ and James looks at this and says, ‘Well, thank God we’re not there.’

“I admired his courage when he got out of his Wolf at Monaco in ’79 and said he’d didn’t want to risk his life any more. Later he had serious financial problems. He became a different man, more humble, more cheerful. This, I think, was the James that had lived inside him all the time.

“He was probably the outstanding British character and personality of all time in Formula 1.”

“James was a very quick racing driver and he remained so in 1977 and ’78 before he went to Wolf, but he began to lose his motivation. Remember, he was on pole for the first three races of ’77 and finished second in Brazil – but I think the decline of McLaren let him down in those two years.

“James knew how to be a racing driver. He’d learnt a lot from Niki Lauda but his heart wasn’t in it any more. He certainly had no interest in testing the car. He partied too much, didn’t want to put the effort in and his motivation fell away. Any kind of setback would de-tune him. He became more introspective, more concerned about the safety, the fragility of life, and he was less keen on taking risks.

“I think Gilles Villeneuve turning up at McLaren in ’77 unsettled him. James knew how fast, how smart Gilles was. Then there was the crash at Monza in 1978, when Ronnie Peterson was killed. That affected him badly and I felt that was a turning point. I think deep down he thought some of what happened was his fault, though it was Riccardo Patrese who took all the flak. I never knew why he went to Wolf in ’79. Maybe it was for the money as he wasn’t well paid when he joined McLaren. He just said ‘I’m off’ and that was that.

“People will always be interested in James because he had real charisma. He could start a party at a bus stop in Bognor Regis. If the bus didn’t come, he’d flag down a car full of girls, get a party going.”

“I was only six when Dad died but I’ve heard so many stories from racing people like Murray Walker, Alastair Caldwell and other drivers, and watched lots of videos of him when he was in Formula 1. It’s weird but it’s almost as if I know him better now than I did when I was a child. “I drove his 1976 McLaren at Silverstone and that was emotional, sitting where he sat when he won the world championship. I was thinking about what it must have been like when he won the British Grand Prix in 1977 in front of his home crowd.

“As a child I did go to Silverstone with him but at the time I was more interested in animals, the natural world around me. I didn’t really know the difference between a road car and a racing car. I know that Dad was a competitive person and was good at many sports, and I’ve inherited the joy of competing which is why I started doing some racing myself. So I guess his fighting spirit, his desire to win, is in the genes.

“I enjoyed Rush but what upset me was that Chris Hemsworth never spoke to our family. He never asked us about Dad, what he was really like as a person. By contrast Daniel Brühl spent a month with Niki and I think that showed in the film. I still don’t think Hemsworth came across as my dad, or the man I remember, and I’ve now heard so much since meeting so many people in motor racing who knew him well.”