Benetton: when F1 was in fashion

In the 1980s Benetton emerged on the grid to reach a global audience for its clothing. Damien Smith tells how a rebel brand went on to rattle the F1 establishment

Benetton Group

Take a step back for a moment. An Austrian company that sells a sickly sweet, fizzy energy drink is the dominant force in the world’s most technically sophisticated and complex sport, thanks to its committed patronage of a British-based Formula 1 team. It’s become normal now so we take it for granted, yet it’s still amazing. But doesn’t that premise sound familiar? Twenty years before sorry Jaguar morphed into brash and disruptive Red Bull Racing, Benetton got there first. The parallels are uncanny.

Benetton’s first foray into Formula 1 was as the main sponsor of Tyrrell in 1983.

Benetton Group

That much emerged time and again during the four years it took to research and write a newly released book on Benetton, coined as the Rebels of Formula 1. Red Bull has big characters at the top in Christian Horner and Helmut Marko, a genius designer in Adrian Newey, totemic drivers in first Sebastian Vettel and now Max Verstappen, and an enigmatic figurehead in the late Dietrich Mateschitz. Likewise, a cast of giant characters pepper the Benetton story: most obviously the flamboyant Flavio Briatore, his more grounded predecessor Peter Collins, the great Ross Brawn, Tom Walkinshaw, Pat Symonds, another of F1’s most inspirational designers in the shape of Rory Byrne, a divisive genius in the cockpit during the team’s mid-1990s heyday, Michael Schumacher – and at the top an arms-length figure around which there’s a degree of mystery, Luciano Benetton. Colourful stories abound when it comes to this spiky, controversial team, again just like Red Bull. But what I kept coming back to as the book took shape was the question why. Why did a garish, impertinent Italian fashion house known for its provocative ad campaigns and colourful woolly jumpers and T-shirts end up owning an F1 team in the first place? What was it all about?

“Its billboards embraced taboo subjects – Aids, sexuality and race”

“Yes, it is quite interesting,” muses Pat Symonds, who was there through it all, from the team’s roots as Toleman to the Benetton buy-out in 1985 and beyond the company’s F1 exit in 2001, after it had sold the team to Renault. “I’ve spent 40 years in F1 and have listened to a lot of marketing people talk up their great sponsorship leads, but nine times out of 10 whether they go for it or not comes down to the person who can make the decision, whether it’s the owner, CEO or commercial director.

“If he likes golf, he’ll sponsor golf. If he likes cricket, he’ll sponsor cricket – and if he likes motor racing… it really is as simple as that. The strange thing was with Luciano Benetton and the whole family, I never really saw that passion for motor sport. Luciano is a fantastic guy, a remarkable character in every respect, as a businessman and as a person. I really liked him – even though we didn’t have a great deal to do with him.”

I wasn’t sure I’d ever get to the bottom of this fundamental question. Then right at the end, just before I was about to press send on the manuscript, a breakthrough. Through former Benetton marketing executive Patrizia Spinelli, I finally made contact with the Benetton family. At 88, Luciano Benetton wasn’t available. But would I like to meet Alessandro Benetton, his oldest son and a figure who played a direct role in representing the family’s interests during the F1 era? I caught a flight and met Alessandro in the offices of Edizione, the Benetton family’s holding company, of which he is chairman and which is based in Treviso not far from Venice, a short drive from the original clothing factories.

Scroll back to the mid-1980s and those provocative marketing campaigns defined Benetton as much as its lairy-coloured garments. Under inspired art director and photographer Oliviero Toscani, a series of billboards embraced taboo subjects such as Aids, sexuality and race. The Benetton name and squiggle logo – a render of the texture of a fabric known as folpetto or polipetto (octopus) – first appeared in F1 as a sponsor on Tyrrells in 1983. Luciano Benetton, company co-founder with his three siblings, had no obvious attachment to motor sport. Rugby was and remains the primary sports arena favoured by the knitwear firm. But the F1 seed was planted by a couple of sources. The first was an industrial partner and son of a wealthy textile merchant, who in the 1970s had made 17 F1 starts: Giovanni ‘Nanni’ Galli. The other was Benetton’s new head of communications, Davide Paolini, who recognised a synergy between F1’s increasing global profile under Bernie Ecclestone and Benetton’s own ambitious international expansion. The US market was a priority, which partly explains why Kentuckian (and former Tyrrell ‘gofer’) Danny Sullivan ended up as team-mate to Michele Alboreto.

Pat Symonds came with the Toleman fixtures and fittings

Getty Images

Alessandro Benetton made intermittent appearances on the pitwall before and during the years when Michael Schumacher carried this perennial ‘rebel outsider’ (and serial underachiever) to double world title success in 1994 and ’95. Now 59, he was also present as a teenage witness when his father struck that first F1 deal with Ken Tyrrell. He says Luciano recognised in F1 a collective kindred spirit and explains the Benetton business approach was never just about selling its woolly garments. “F1 was a practical way to testify a very strong willingness from my father and the whole family to ‘disrupt the system’,” he says. “[Toscani’s campaigns] were not advertising directly a product, but a concept, to associate a name and a brand to an attitude that touched on very tricky areas. It did require a lot of courage. Nowadays [the adverts] are recognised as a big success, but back then those campaigns were not so straightforward. There were a lot of questions: why are they doing it? But this was just a way of saying it’s time to make a statement. And F1 was not so different from that.

Benetton made an instant impression on the grid with its liveries. This one is from 1986, with its brush strokes conveying ‘speed’

Benetton Group

“The common denominator was opportunity and a willingness to find a global way of communication. The company wanted to expand globally. It wanted to be associated with dynamism and action, being courageous and young, a daring attitude that was typical of F1 – and F1 was the only global sport. There was no alternative to it. The bottom line is it showed an attitude of the entrepreneur, who had courage to do it. This is very important.”

“F1 was a way to testify the willingness to ‘disrupt the system’”

Benetton spent only one year with a Tyrrell team increasingly out of touch with a fast-changing F1 world. But Alboreto’s victory in Detroit, what turned out to be Tyrrell’s last in F1, helped open Luciano Benetton’s eyes to the sport’s true power. Hindsight tells us Tyrrell let slip a sponsor that might have pulled the team from its long, slow spiral. What happened? “I learnt something very important, even though I was only a teenager,” says Alessandro. “Ken Tyrrell said, ‘OK, we are [among] the most successful teams ever.’ He would start with statistics, from the 1960s. But the reality was it was a declining story. He was a great guy, and his son was too. They were a team with a great tradition and a great name. I’m not an expert, but if I have to speculate, it was the beginning of a decline in the ‘Mama and Papa’ approach in an industry that was becoming more sophisticated. It was less a family business, and teams needed to invest. But I don’t think there was a conscious observation [in the decision not to renew the agreement for 1984]. I think it is an observation that we can make today. My father voted to move forward. And through that victory [in Detroit] he got the feeling that to do so, to have more of an impact and utilise F1 even further, being a sponsor was not enough.”

Michele Alboreto gave Tyrrell its final F1 win at the 1983 Detroit GP, with the Italian’s overalls carrying the Benetton name to a worldwide audience

Getty Images

Luciano chose at first to turn Alfa Romeo’s mostly misfiring F1 team green for two years, but it was early in the second of those seasons, in 1985, that he agreed a deal to buy Toleman. The British transportation specialist had enjoyed a long association with club-level motor sport dating back to the 1960s, and it was the company’s ambitious managing director, Alex Hawkridge, who had set it on a course for F1. Toleman always trod its own path, from the beginning. In 1980, its own TG280 conceived by Byrne and John Gentry had blitzed through European Formula 2 with Brian Henton and Derek Warwick, so naturally Hawkridge pressed on straight into F1. He could have bought a supply of Cosworth DFVs like most other F1 wannabe constructors, but instead stretched his F2 alliance with Brian Hart to create the team’s own, bespoke turbo engine and stuck with Pirelli too for an alternative tyre source.

Luciano Benetton with Tyrrell driver Michele Alboreto, 1983

“This was the incredible naivety we had,” says Symonds, who had designed Hawke Formula Fords, then Royales and was now recruited by Hawkridge for Toleman’s brave next step. “I was employee number 20 and started on January 2, 1981,” says Pat, who revelled in the chance to work with old pal Byrne. As he admits, “We just made work for ourselves, because we felt it was the right thing to do. And you know? If Alex and Ted Toleman had said, ‘Let’s go F1 racing, let’s buy a DFV,’ we’d have been a hell of a lot more successful in 1981 – but we wouldn’t have been around by 1990. We’d have been just another team.”

By 1984, Toleman’s rebel approach was paying off as Ayrton Senna broke through in that famously truncated wet-weather Monaco Grand Prix. But his contentious decision to ditch Toleman for Lotus for ’85 left an already disenchanted Hawkridge feeling betrayed. The team had lost its star driver and now, more pertinently, the new and promising TG185 was left on bricks by a lack of tyre supply. Toleman had earned the wrath of Pirelli by switching to Michelin in ’84, but now the French manufacturer had pulled out of F1 – and somewhat understandably Pirelli didn’t want to know. Neither did Goodyear. Hawkridge had ruffled feathers along every step of the way, and now he was done with F1.

Benetton-branded Toleman TG185 at Brands Hatch, 1985

Getty Images

Benetton’s livery ideas screamed ‘Colors’.

Benetton Group

The history books record that Benetton’s first season as a full-blown F1 constructor was 1986, but team insiders count the previous year as the real start of the new era – whatever it said above the garage and on the chassis plates. “It stopped being Toleman at the end of 1984 and it became Benetton from the start of 1985,” asserts Hawkridge, who took responsibility for a traumatic and far from certain transfer of power over the winter and deep into the start of the new season. But once the change of ownership was confirmed, Pirelli agreed to supply tyres and Teo Fabi gave a lone TG185 its debut at Monaco, running in a livery sporting national flags over the rear bodywork, plus Benetton’s logos.

Again, Alessandro Benetton credits Paolini – today something of a forgotten figure in F1 – for leading his father to Toleman’s door (although somewhat inevitably Bernie Ecclestone also played a hand in the alliance). Given Hawkridge’s singular approach, the team based out of humble industrial units in Witney was a perfect choice for edgy Benetton. Both were rebels of their particular spheres. “In that sense, you could read it this way,” agrees Alessandro. “[In contrast] Alfa Romeo was a public company because it was still owned by the government, if I remember correctly. It was very institutional: you break a piston and they would tell you, ‘OK, we’re going to make another one.’ Nobody would say, ‘Why did it break?’

“Davide came across Toleman which was in a difficult moment. He came back and said, ‘Listen, there is this engineer, Rory Byrne, who is really good, but he has no budget.’ There was some sort of desperation. You know, during moments in which things are not going well there are opportunities, and I think it was a reciprocal opportunity for the team to have some sort of continuation.”

The B192 was a podium regular in ’92

Benetton Group

I asked Hawkridge how much he sold the team for. He wouldn’t tell me. But in Benetton Formula 1: A Story, an officially sanctioned account of the company’s F1 years, Luciano Benetton himself quotes the sum: just £2m.

“FOCA rules meant the team ran as Toleman throughout 1985,” says Hawkridge. “The name-changing rules meant we had to be careful, plus Benetton needed my support to settle them down and advise them on any major issues, but there weren’t any. They came in, picked up from where we left off, kept our existing financial management and like a lot of racing teams it was run like a proper business. It had filed accounts and a lot of detail. So they were comfortable.”

“Nowadays it would be more understandable to make this investment,” says Alessandro. “Back then it was really thinking out of the box. And after a shaky beginning we started doing better and better. Eventually we won some grands prix.”

“After a shaky beginning we started doing better and better”

Well, in the early days it was just the one, when the high altitude in Mexico City allowed Gerhard Berger’s BMW-powered B186 to run through on a single set of Pirellis – no chance of that today! Beyond that special day, the second half of the 1980s was largely characterised as an era of unrealised high potential as the team switched from its supply of Heini Mader-tuned customer BMWs to a Ford V6 TEC turbo known internally as the GB for 1987, then on to the 3.5-litre normally aspirated DFR V8. Peter Gethin, winner of the closest-ever F1 grand prix at Monza in 1971, had a brief spell running the team – “Lovely bloke, useless team manager,” is Symonds’ blunt verdict – but it was Peter Collins, a veteran of both Chapman-era Lotus and Williams, who steered the Benetton ship through F1’s transitional years from turbos back to normally aspirated engines. Both Symonds and Byrne credit Collins for his steady hand and direct leadership, and Alessandro Benetton too has a high opinion. “I have great memories of Peter Collins, a great guy and we had great moments together,” he says. “Of course, he was Australian, he had his own way. But in a good manner. He was a very classical manager and focused on the positives. Our progress started back then. We were the third- or fourth-best team. People think that it was a disaster, but that was absolutely not true. We were competing. Of course, there was two different leagues. There was McLaren and Williams, and then we were there. Ferrari was up and down. But we were in that crowd.”

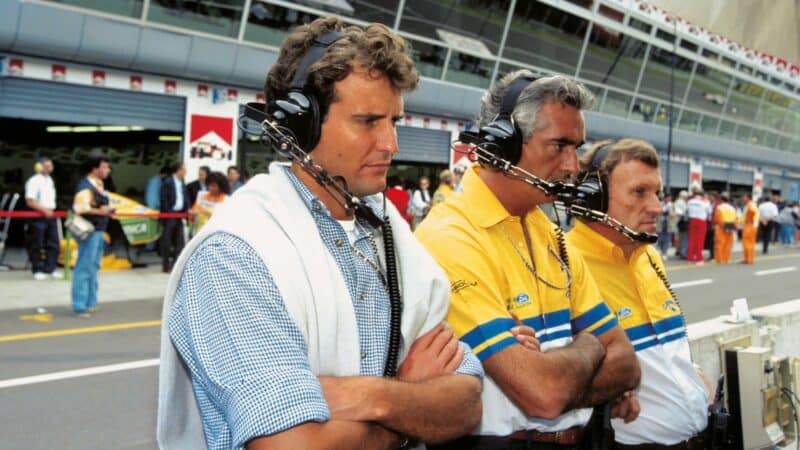

From left: Alessandro Benetton, Flavio Briatore and Tom Walkinshaw, whose TWR empire forged an alliance with the team

There is an agenda here, though. During our interview it became clear Alessandro was keen to claim back the Benetton story from the deep-tanned character who came to dominate the team, and in effect ousted Collins during a rocky 1989: Flavio Briatore. He’d been working for Benetton in the Caribbean when Luciano Benetton took him to the 1988 Australian GP. Briatore was unimpressed by a world he knew nothing about and cared for even less – but still found himself dispatched to Witney (wherever that was) to shake the tree. “The storytelling has been a little bit biased from my point of view,” says Alessandro, who became chairman of the team at his father’s behest in 1988. “If we had not had those early results, we would have not got to the next stage. People forget that. We went on and took even more risks, because Briatore was a risk as well. He was not an expert of the industry. The question is, why did we take that risk? We took that risk because we already had results.”

Nevertheless, whatever some think of Briatore – especially in the wake of the Singapore GP controversy of 2008/09 in the later Renault era – it was under his hand that the rebel F1 team became a part of the establishment. The short, volatile but pivotal John Barnard era; the new alliance with Tom Walkinshaw that brought Ross Brawn into the team; the Schumacher scoop from under Eddie Jordan’s nose in 1991; the move to a state-of-the-art base near Enstone; the team coming of age to win a world title in 1994, only to be undermined by an endless string of controversies that included the dark shadow cast by insinuations of cheating on traction control; then the retribution year of 1995, when Schumacher won a second title now with Renault power and without a blemish (well, not many…). Briatore was at the heart of it all and much more. Even if he only ever knew the names of his most senior engineers.

There’s much water under the bridge when it comes to Benetton and Briatore, and you sense credit is only given grudgingly by Alessandro. The family was often at arm’s length from day to day operations, both by choice and because that’s the way Witney/Enstone liked it – but what did they make of 1994 and the damage left by the cheating accusations that still hang over its achievements that year?

Proof that Benetton hasn’t forgotten its racing past. This is the company’s collection housed in the Castrette buildings, a former industrial complex that now houses Benetton’s heritage and archive department, near Ponzano Veneto. The collection includes a Tyrrell 011, an Alfa Romeo 184T, a Toleman TG185 and one of every Benetton up to the B198.

Benetton Group

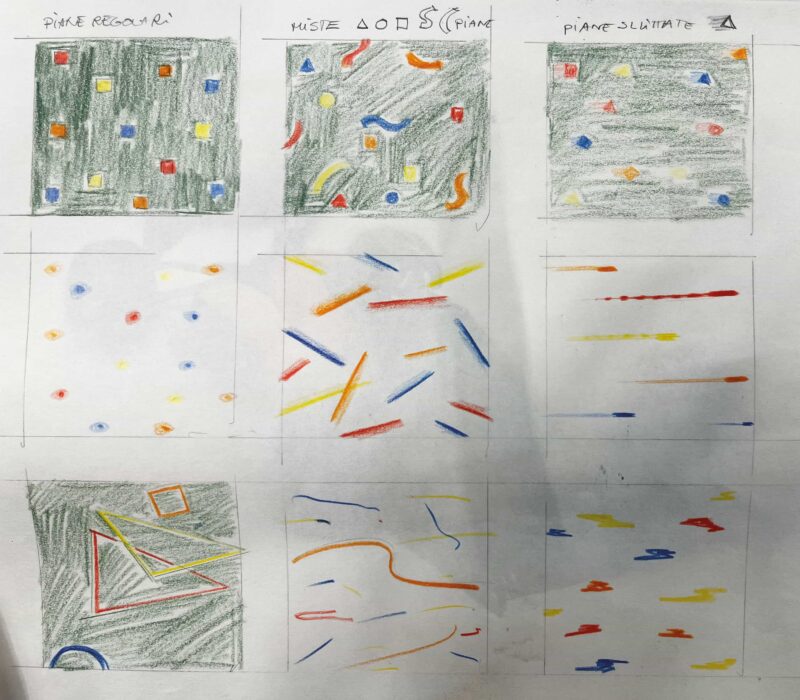

Fashion meets F1 in the bold and brash late-1980s. Basic Benetton sketches for the team’s ‘patchwork’ livery introduced in 1987. Note the Union Flags on the top one

Benetton Group

“There was a mixed feeling,” he answers. “We had delegated the management of the team. There was a question, a balance: we know Flavio is a creative guy, so how much can we control him? At the same time we had the impression there was some sort of rejection from the establishment, in accepting that a newcomer could become so successful so quickly. Personally, the impression that I had was in a world that had a reputation for being technologically advanced, with incredible research and incredible minds working at incredible problems, the fact that some guys making sweaters could get into this industry and demonstrate that you could actually do it was considered somehow detrimental to the overall system. You’re telling the world that this was an inaccessible, highly sophisticated and difficult technical world and now anybody can do it – and they didn’t like it. So how can they explain that anybody can do it? ‘Many ways – but maybe they were cheating as well.’ That was a little bit of a dominant factor, if I had to guess. We were very active and dynamic.”

“I think getting directly involved today, the numbers are just huge”

In the book, Symonds, Byrne and others describe the sense of vindication they felt in 1995, how the traumas and accusations of 1994 nearly drove them from F1 in disgust. Alessandro Benetton agrees that the second title, when Benetton also beat Williams to its only constructors’ crown, carries a special resonance. “Yes, also taking into consideration we had unquestionably the best engine as well,” he admits. “It was different to 1994. That season was a little murkier, for many reasons. Because of Ayrton Senna’s death, because of the difficulties of Williams at the beginning of the season and other episodes including the last grand prix in Australia where Michael was particularly aggressive [with Damon Hill]. Yes, 1995 was more straightforward in the sense of results. But it goes back to what I was saying: if you look at the chain every link is linked to the one before. In the world of sports somebody told me once that the more you win, the more you train. The more you train, the better you get. The better you get, the more you have fun. The more you have fun, the more you train. I think this is true from any perspective in any function within a given industry.”

Emanuele Pirro in the B186 with Benetton team manager Peter Collins during testing at Donington, 1986

Sutton

Once Schumacher left for Ferrari, to be followed by Brawn and Byrne, Benetton’s final chapter across six long seasons is one of diminishing returns and dwindling fortune. The team was sold to Renault in March 2000, but in an echo of the Toleman/Benetton transition, the company didn’t officially leave F1 until the end of 2001 – by which time the Renault rebuild was already well underway. “We had pressure to sell and there was strong interest from Renault,” recalls Alessandro. “It was somehow a thermometer of the time. Mercedes wanted to be involved, then BMW was getting closer to Williams. So it was a case of OK, you know, there’s no more time.

“Eventually history demonstrated with Red Bull that it was not the end of the scene [for independent teams]. But it was quite clear it was the end of some sort of cycle. The objective had been achieved. It had been a 15-year story – not a short one. It was time.”

He makes mention of Red Bull. I drop in the point about the parallels. “Yes, I like to see that. I’m not involved in F1 now. I’m told that it’s coming back so strong because of this TV series [Drive to Survive]. I like to think they got a little bit of our inspiration in having the courage to do it.”

In 1995, the B195 gave Michael Schumacher and Benetton their second drivers’ title, and a first constructors’ championship

Benetton Group

Might we ever see Benetton back in F1? His answer suggests it seems unlikely. “At the moment, given what I’m told about the numbers, it’s not doable for the size of our business. But I recently talked about F1 to this friend of mine who is in F1 as a sponsor and he was telling me they are happy about the enormous level of visibility. Of course, they are doing it only as a sponsor. I think getting directly involved today, the numbers are just huge. But it’s interesting to keep an eye on this new phase. New media, new TV formats are creating a new opportunity. So anybody should keep an eye on that.”

As Alpine, ‘Team Enstone’ today has become a part of the establishment it fought against for so long. But there are still a number within its corridors who were there in the Benetton days.

The colours have changed but for those on the inside the old Benetton us-against-the-world spirit still thrives. Once a rebel, you can never be tamed completely.

Benetton: Rebels of Formula 1

by Damien Smith

Published by Evro, £60

ISBN 9781910505588