But before clouding those clear blue Monte Carlo skies let’s indulge in that optimistic moment as the towering blue truck rolls noisily into town with American hopes stacked high on its rattling double decks. It’s been here before: commissioned by Maserati in 1956, originally on a two-axle Fiat bus chassis, it went to commercial vehicle coachbuilders Bartoletti who assembled the same double-deck, three-cars-plus-lockers pattern they supplied to Ferrari, Lancia and others. In striking blue and yellow livery, it carried the Modena Grand Prix team to a triumphant 1957 title before Reventlow bought it when Maserati wound down its Grand Prix operation in 1958. Now after a steady slog from RAI’s British base it’s back in the principality, repainted in Reventlow blue. Beneath the floor the six-cylinder fuel-injected Fiat diesel oozes torque enough to heave the bus over an Alp or a Pyrenée (if they make it through to the Monza and Oporto rounds) while being in little danger of collecting speed tickets – 60mph is a brave target, even with air-boosted brakes.

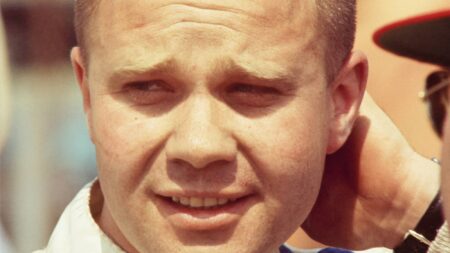

As winches thrum and cables clank to lower the racers to the Monaco ground there’s a supportive atmosphere – new teams are welcome variety as long as they don’t look too promising, and Reventlow is continuing in the admirable mould of compatriot Briggs Cunningham – the wealthy, leisured, cultured sportsman, the trans-Atlantic equivalent of Rob Walker. And Reventlow’s team-mate is Chuck Daigh, known as a tough and gritty driver and someone new for the Europeans to measure themselves against.

Drivers and mechanics stroll over to see what the truck has delivered. Within the Scarab’s sturdy but conventional steel tube frame, Goossens’ four-cylinder lies almost flat with driveshaft under the driver’s left arm feeding a rear transfer box, yet against this lower centre of gravity the driver sits up at a bus-like wheel. Fuel injection feeds the motor, but it breathes through desmodromic valve gear that needs another season – or two – to sort. When asked about power, the team mutter about a 260hp target; later Daigh would concede 220 was about the best so far. Ferrari’s Dino V6 is handing out 280.

Reventlow’s efforts are unheralded, despite being an American trailblazer

Matthew Howell

Sharing a pit with the compact Coopers, the Scarab seems a weightlifter to a hurdler. Motor Sport’s DSJ is unimpressed: “The only newcomer on the scene has been the four-cylinder Scarab engine. As this was an almost open crib of half of the 1954 Mercedes-Benz W196 engine, with desmodromic valve gear and near-horizontal cylinder position, it can hardly be considered to be progress”.

Events wouldn’t belie that view. In practice the Scarabs prove heavy, underpowered and slow, so slow that Reventlow asks Stirling Moss to see if he can extract anything extra. Later in Motor Sport Jenks tries to be kind: “Just to see if it was the cars or the drivers, Reventlow let Moss try one. He did 1min 45sec, which equalled Jimmy Clark’s best time with the Lotus-Junior, so the answer to the Scarab trouble was cars and drivers. However, there were other factors, such as first time out, first attempt at anything so exacting as Monte Carlo, and the simple fact that their Goodyear tyres are not as good as Dunlop tyres. A set of Dunlops would certainly have given Moss 1min 43sec. If it had been his own car and fitted him properly he would have done 1min 42sec, and if he had been trying he could have done 1min 41sec, and if starting money had been involved he would have got down to 1min 40sec, which would have been a reasonable time for a new car to new conditions.” Moss’s pole time was 1min 36.3; Trintignant’s tail-end slot, 1min 39.1sec.

The ramps on the Bartoletti come down again, the winch whines, and the cars are loaded up. The deflated debutants are leaving the ball without being asked to dance.