Mystery of the third man in Rindt & Gregory's Le Mans 1965 win for Ferrari

Back in 1965, Jochen Rindt and Masten Gregory won the world’s greatest race. But 34 years later it was claimed they had some illegal assistance. Doug Nye dons his deer stalker and investigates

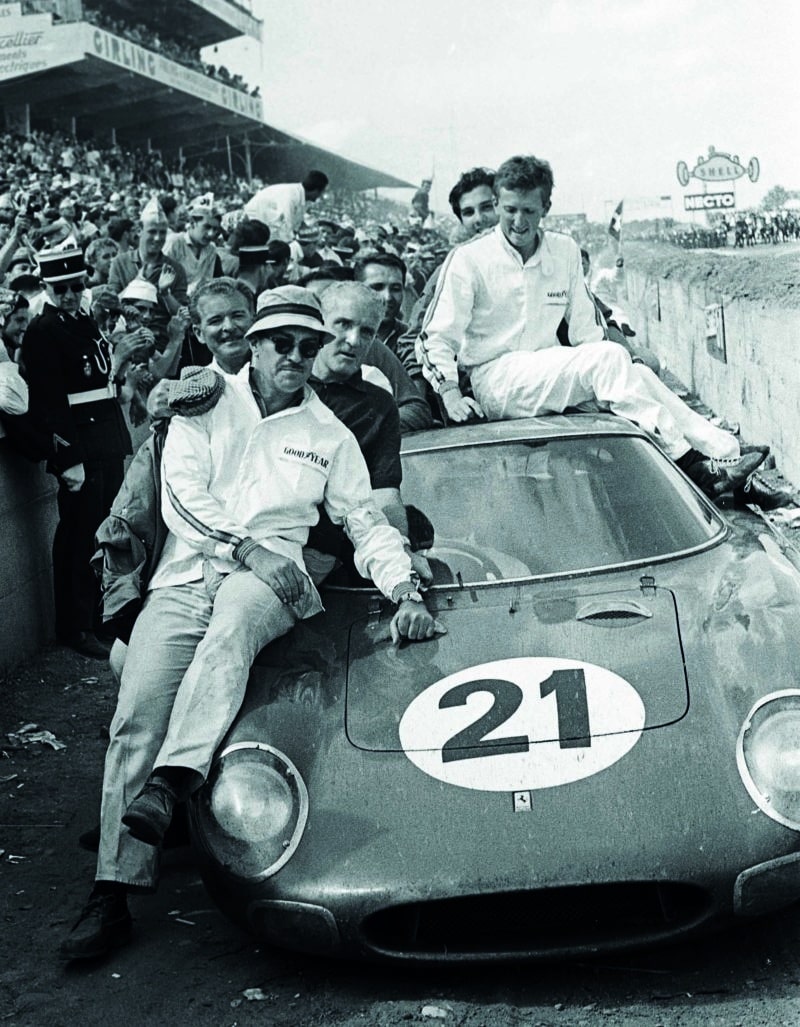

A knowing smile? Ed Hugus perched at the rear of the winning Ferrari 250 LM, in hat and dark glasses. But did he actually drive it, as he much later claimed?

McKlein

Official race results, once confirmed, are seldom questioned. This is certainly true of the most prestigious surviving road race of them all, the Le Mans 24 Hours.

Back in 1965 the frontline battle between Ferrari and Ford meant the pace-setting prototypes struck trouble, leaving outright success to the minor category contenders, the rear-engined Ferrari 250LMs entered by Luigi Chinetti’s North American Racing Team (NART) and by privateer Pierre Dumay and the Equipe Nationale Belge. Their battle was resolved when the latter’s LM burst its right- rear tyre, which cost it five laps. The NART LM co-driven by veteran Masten Gregory and fast-rising new Formula 2 star Jochen Rindt then paced home to present Luigi Chinetti with his fourth Le Mans 24 Hour race victory, three times before as a driver, but this time as an entrant.

It was a popular result. Bespectacled Masten Gregory, the little 33-year-old ‘Kansas City Flash’ with his improbably deep bass voice, was immensely experienced in both sports and Formula 1 cars. This was his tenth Le Mans. For 23-year-old Jochen Rindt, this was only his second.

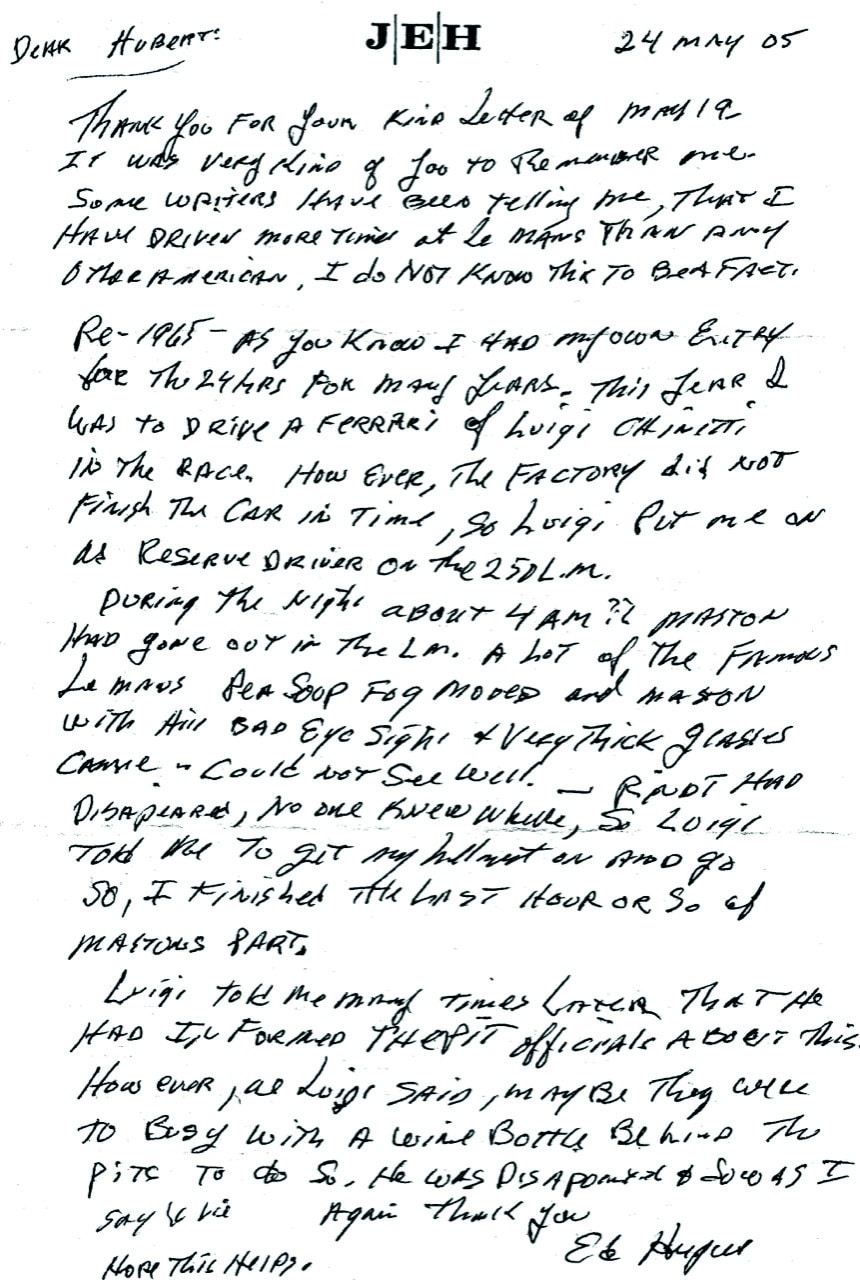

Their great win sat peacefully in the record books for 34 years, until our friend János Wimpffen’s remarkable twin-volume endurance-racing history Time & Two Seats was published in 1999. János is a most diligent researcher, so when he wrote: “During the early hours when it was Gregory’s turn to drive, he became concerned about his rather poor night vision and asked reserve driver Ed Hugus to spell him briefly until first light” – we all sat bolt upright, and took notice.

János’ reasons for including the story were “…primarily based on Ed’s own story. I believe that I was the first to whom he had emphatically told it and was definitely the first to have published it. I met with him numerous times and spoke several more times over the phone. The story was always consistent and had a logical pattern to it. It was also consistent in how he told it to others…” but “…Quite conveniently the story emerged after all the principals, the last being Luigi Chinetti, were all gone”.

The NART Ferrari 250LM was driven largely flat-out at the insistence of Rindt, and triumphed when the prototypes hit trouble

DPPI

Ed Hugus – 42 years old in 1965 – headed the European Cars VW distributorship in Pittsburgh. He was a capable and seasoned SCCA racer and in 1962 he funded Carroll Shelby’s new Cobra project, European Cars actually completing the first Cobra batch imported from AC in England. He had raced Jaguar, Mercedes, Cooper, Alfa Romeo, Ferrari, Chevrolet, Porsche and Lister cars, even an Iso Grifo and a Lotus 23 with an ex-NART Ferrari Dino V6 engine. He had driven nine times at Le Mans 1955-64, twice finishing seventh – in 1958 with his own Ferrari 250TR and then in 1960 in a NART- entered Ferrari 250GT. He was certainly a capable and competent racing driver.

In 2017 Dalton Watson published Cobra Pilote – The Ed Hugus Story, by Robert D Walker. It’s a lovely book, beautifully printed and packed with startlingly rare contemporary photographs.

Regarding Le Mans 1965, Hugus was quoted as follows: “I arrived at Le Mans and expected to drive my own NART Ferrari entry, which was to have been delivered at the track by Ferrari in time for pre-race practice”. The author then continued: “He was disappointed to learn that his Ferrari had not been finished in time… Since he was still part of the NART racing team… Chinetti… assigned [him] to fill in as relief driver with… Masten Gregory and Jochen Rindt. If either of those drivers dropped out or was unable to drive, Hugus would fill the void”. Some dispute is recorded between Gregory and Rindt over race strategy – the American preferring a conservative pace, the Austrian charger maximum effort. Rindt was reputedly adamant they should go for it – I can just hear him insisting so – and Hugus told his biographer: “Gregory reluctantly agreed”.

Luigi Chinetti then delegated Hugus to help NART’s veteran ex-Cunningham team manager Johnny Baus in running the pit once racing commenced.

Years later, in May 2005, the elderly Ed Hugus wrote the letter below to French Le Mans fan Hubert Baradat who had requested his story of the race.

So, did Ed Hugus really replace Masten Gregory for a driving stint “about 4am” on the Sunday morning at Le Mans 1965 – or is this an elderly once-sporting gentleman’s wishful thinking?

In the Hugus book Robert Walker writes: “Sceptics who doubt Hugus’ testimony did not know Ed Hugus. His word was his bond and he never promoted himself, embellished his accomplishments or bragged about his success… His only motivation for explaining the details from the 1965 Le Mans race was his passion for details and definitely not for his own notoriety”.

We did not know Ed Hugus, but we know others who did. One Porsche specialist friend recalls him having “a big-time car dealer’s ego, and him telling me when he retired his Porsche from Le Mans in 1959 he was leading – not true”. A major US collector whose father and family were very close to Hugus adds: “Ed was inclined to telling good stories… but I never recall him claiming to have won Le Mans until very late on…”.

Today, Louis Monnier is the immensely enthusiastic and very knowledgeable administrator of the Le Mans organising Automobile Club de l’Ouest’s Heritage Committee. Fabrice Bourrigaud curates the ACO’s archives. For us they have now unearthed and helped analyse the Club’s surviving official 1965 race records.

Ed Hugus leans on the front of the winning machine, wearing the same outfit he had all race

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Did Rindt simply drive a rapid double stint through the night? The records suggest he did

McKlein

Le Mans officials oversaw each stop closely, so would it really be possible for a third driver not to be noticed?

Getty Images

The archive offers three parallel sources: the Journal de Course official record of pit stop timings and work carried out, driver changes, retirements etc, as reported in real time by the pit-lane commissaires. There’s a separate listing of race order at the end of each hour. And there’s the surviving original lap chart with each car’s individual lap times.

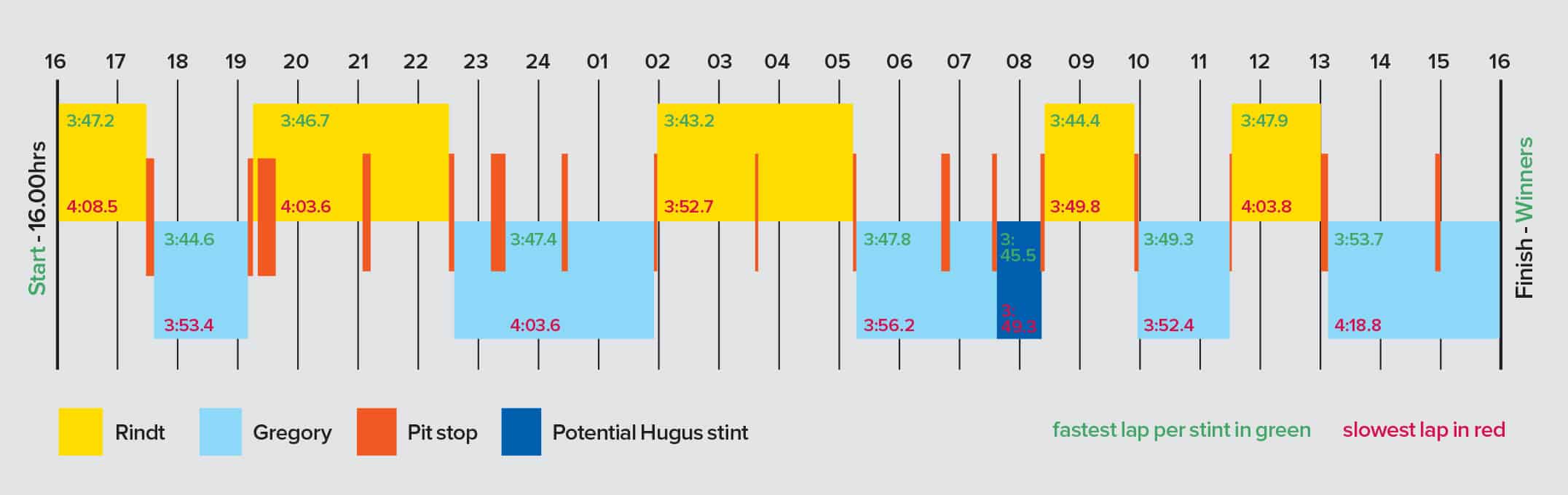

Combining these sources now provides the clearest picture yet of the winning NART Ferrari 250LM’s progress, with some caveats. There is some variation between pit-stop timings listed in the Journal de Course and those recorded more precisely from addition of the car’s individual lap times.

Factors to note: Hugus’ 2005 letter maintains that Masten had begun a stint “around 4am”. The Journal de Course names Rindt specifically as taking over from Gregory in the car’s eighth pit stop, at 01:59 Sunday morning. No driver name is quoted for the ninth stop made at 03:38 but for the 10th stop at 05:14 Rindt is named specifically as the incoming driver, and Gregory as the driver who then rejoined at 05:16.

So Rindt clearly drove a double-stint extending from 01:59 to 05:14, from darkness into the dawn, before handing the car back to Gregory. Hugus says specifically that he took over the car from the vision-impaired Gregory – not from Rindt. But Masten did not take over from Jochen for his fifth driving stint until 05:16 that Sunday morning. He then – notionally – did a triple stint, making the car’s 11th pit stop at 06:44 and its 12th at 07:32 – his third stint finally ending with stop 13 at 08:21 when Masten is named specifically in the Journal as being the incoming driver. Therefore, if Hugus replaced him at all it must have been at either stop 11 or 12. But the car’s average lap time in Gregory’s hands between stops 10 and 11 is 3min 50.3secs, then once Hugus had perhaps taken over between stops 11 and 12 the average lap is still 3:50.8. Between stops 12 and 13, the average lap time accelerates to 3:48.3 and we have confirmation that Gregory was then the pilot in command.

So the lap times for the first two of these three candidate driver stints is consistent between the first two, matching Gregory’s prior pace, but then faster in stint three. Supporters of the Hugus claim might say that Gregory, once back in the car, drove harder to compensate to make up time he might assume that the amateur stand-in had lost – when in fact he had lost very little. Was Ed Hugus a good enough driver to have so matched Gregory’s established pace? As quick as Gregory? Most unlikely.

Bespectacled Masten’s vision was indeed restricted. Talking with Richard Attwood he once admitted he had little peripheral awareness – tunnel vision. Hugus says Masten was troubled by the early morning mist. Certainly mist around dawn was common at Le Mans, but the local weather report for June 20, 1965, lists “25-degrees Centigrade, windy”. We haven’t found a reliable race report citing mist as a problem that Sunday morning, and winds and mist don’t mix.

There may be evidence that something troubled Masten. The LM had its rear tyres and brake pads changed at its 11th stop at 06:44. The car rejoined at 06:52 after eight minutes. The following stint – which would have been the American’s sixth – is brief, however, lasting only from 06:52 to 07:32 – just 40 minutes – and covering only 11 laps instead of the usual 22-24. Could this in fact have been the short stint claimed by Ed Hugus? We doubt it, since the average lap time recorded of 3min 50.8secs is consistent with the average of Gregory’s preceding fifth stint, 3:50.3. While Ed Hugus was an experienced and capable SCCA driver, we doubt very much that he could match long-time professional, world-class Masten Gregory’s pace so closely, first time out in a strange car, mid-race, with so much hanging upon his keeping the car fit and safe…

But while Jochen Rindt lost his life in 1970, Masten Gregory in 1985, and Luigi Chinetti (aged 93) in 1994 – the first most of us heard of Ed Hugus’ claim to have co-driven that 1965 Le Mans-winning NART car was in 1999. One eye-witness survives; Chinetti Sr’s son Luigi Jr, himself a capable endurance racing driver known to many as ‘Coco’.

He has always distanced himself from the controversy, largely – I surmise – in respect to Ed Hugus and – since Hugus’ death aged 82 in 2006 – to his family. But when pressed recently, Luigi wrote: “He always claimed to have been the third driver in the LM but I recall quite clearly seeing him from the start to the end sporting a windbreaker and a golf hat! I can assume if one did even one stint in such a car at such an event one would be wearing race uniform ’til it fell off. I took some photos toward the end and he is in the same outfit.

“No team manager would take a chance on installing a third driver unless one of the other two was unable to continue. Were this the case, all three would have been on the podium smiling happily. I might add that the marshals would or should have noted such an event as would the timer and scorers.

“There were many opportunities for a third driver to have been recognised… Certainly Goodyear as an American company in their big-time international racing debut year would have made a big deal of this… immediately after. They did make a big deal; mentioning only Rindt and Gregory…”.

Supporters of the Hugus story will emphasise that Le Mans rules specified that if one of the assigned drivers was substituted during the race by the reserve then they could not drive again for the rest of the race. Since Gregory absolutely drove again, the NART Ferrari could have been disqualified had Hugus’ involvement been spotted or disclosed. With the fuel tank-sealing plombeur and at least two other commissaires present at each stop – unless all three had been asleep, or ‘in vino’ at the time as Hugus inferred – the ploy would surely have been reported. The truth is they probably were not, and that ‘it’ never happened.

We emerge from this investigation 99 per cent sure that Ed Hugus’ claim simply cannot stand. On the evidence, Masten Gregory and Jochen Rindt won Le Mans 1965, unrelieved by any other driver.

Post-race pose: Johnny Baus (blue shirt), Rindt, Hugus (in that golf hat), Gregory and Luigi Chinetti Jr (blue jacket)

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

The tale of the tape

To solve the mystery of the third driver who perhaps never was, Motor Sport has delved deep into the official race records held by the Automobile Club de l’Ouest within its archive. The data is taken from multiple documents created during the 1965 race, and checked against the Journal de Corse. It allows us to illustrate the recorded driver stints.

As we can see, there is no driver change logged around the 04:00 mark, confirming that Rindt simply drove a double stint. There is a later, potential, window just before 08:00 when Gregory stopped without much explanation. However, if Hugus took over here he would have been significantly quicker than Gregory, in his first outing in a new car. Doubtful, at best.