When Murray Walker joined ITV's F1 team: Exclusive book extract

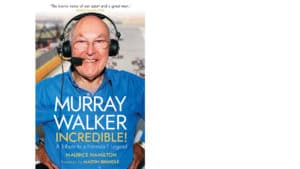

A new biography of the late Murray Walker by F1 writer Maurice Hamilton will celebrate the voice of motor racing like no other. The highly anticipated book is published in the autumn, but with this exclusive extract Motor Sport readers can get a sneak preview of what is to come...

The voice of F1 – Murray Walker was a full-time commentator until 2001. Here he is on ITV duty at Monza towards the end of the 2001 season

Speculation had ended on Monday September 23, 1996 when it was revealed that Murray Walker would be ITV’s main Formula 1 commentator. The announcement was made by MACH1, a trading name devised from a coalition of the Meridian and Anglia ITV channels, plus Chrysalis, Neil Duncanson’s production company that, a few days before, had won the five-year contract. Having secured their key player, MACH1 would continue to put together the rest of the broadcasting team, with particular focus on the commentator to accompany Murray.

Martin Brundle was mentioned in various speculative media reports. But the man himself was not so sure – primarily because he was, first and foremost, a racing driver. Martin had just completed his 11th full season of F1, Jordan having been one of several different teams the Englishman had raced for across 158 grands prix. Still chasing that elusive and much deserved first win, the 37-year-old continued to have his eye on racing F1 cars rather than talking about them.

Brundle did, however, have a brief experience of broadcasting – thanks to the extracurricular activities of James Hunt. Much to the alarm of the BBC team, James had failed to turn up on race day for the 1989 Belgian Grand Prix at Spa-Francorchamps.

“James was not to be seen, five minutes before the race, five minutes into the race; 25 minutes into the race – nothing,” recalled Murray. “I was doing it alone and Mark [Wilkin, BBC Sport producer] was getting anybody who had retired from the race to come to the commentary box. James never turned up. He apologised afterwards. He said: “I’m terribly sorry I wasn’t there. I was in bed with a stomach complaint.” And I thought – it’s the first time I’ve ever heard it called that! But the point is, this was when Martin Brundle did his first talk on TV and the first occasion when we started to discover how good he was.”

“I was driving for Brabham in 1989,” said Brundle. “The car was quick at times, but unreliable. Spa was one of several retirements. When that happens you just want to get away from the race track as soon as possible, but on this occasion I was out quite early in the race and I got dragged up to the BBC box to help Murray out and comment on what was going on in the race.

“One of the problems with Spa is the horrendous traffic after the race. I remember sitting there thinking: I need to get out of here. As soon as I could, I slipped away. When I spoke to my manager the next day, he said: ‘Why did you stop? It was going so well. Were you crazy? You should have stayed up there.’ I have to admit I found it interesting that I got quite a lot of nice feedback.”

Walker played a crucial role in easing the nerves of ITV Sport’s new F1 presenting team in 1997

On Monday January 27, 1997, Brundle was part of a seven-strong team announced by ITV. Simon Taylor (formerly BBC Radio) and Tony Jardine (former BBC pitlane reporter) would offer analysis from a studio on site at each grand prix; pitlane reporting would be handled by Louise Goodman (ex-Jordan press officer) and James Allen (former Autosport news editor), with the seasoned ITV sports presenter Jim Rosenthal hosting a package that promised to give ‘more interviews, analysis, expert opinion and humour’.

A publicity photograph showed the ITV team ranged around a Williams F1 car and incongruously holding white crash helmets, perhaps suggesting they expected flak from an F1 audience nurtured by the BBC and unaccustomed to adverts interrupting their viewing. It was promising to be a particularly difficult role for Rosenthal, despite his vast experience in broadcasting.

“When I got the F1 assignment, it was a bit of a rush job,” said Rosenthal. “Steve Rider had been lined up, but they came to me in early January and said I had the job and it was starting in less than two months’ time. From that moment on, my house sounded like a bloody race track as I went through videos of every grand prix known to man.

“I was obviously very aware of Murray, but I didn’t know him personally. I rang Murray and said: ‘Sorry, you’ve got me doing this. I’m a bit hesitant in asking [for help].’ He said he’d be delighted to help. ‘You’ll be absolutely fine,’ he said. ‘If you need anything, I’ll be here 24/7.’

“What will Murray have? Hmmm! He’s going for porridge. Incredible!”

That was phenomenal; such a comfort to me, it really was. Murray was hugely supportive.”

If Rosenthal was at home in the wider world of broadcasting, it was completely new territory for Louise Goodman. “I didn’t grow up in a massively motor sport family,” she said, “but we did watch the grands prix, and when I got interested in the sport it was at the time of Murray and James; that absolutely iconic partnership. When I began working in the F1 paddock doing sponsorship co-ordination with some of the F1 teams, I remember the great Murray Walker coming up and saying: ‘Hello, dear. Just wanted to say hello; I’m Murray Walker.’ And you think: ‘Oh my God; why is Murray Walker introducing himself to little old me?’ You’re glancing over your shoulder to see if he’s actually talking to someone else. But that was so Murray. He had time for everybody in the paddock, and it wasn’t as if he forced himself to make time; that was just the way it was with Murray.

“The step into broadcasting was obviously a very big one for me – as it was in different ways for the ITV F1 team. We had said we’re changing everything; we’re going to have ad breaks; we’re not going to have The Chain; we’re going to have a bunch of different people; we’re going to have a woman on the crew; we’re going to have this; we’re going to have that. But then to say we’d got Murray Walker meant everyone could feel they were in a totally safe pair of hands. That’s the bit that fans cared about; the bit that made them think ‘Formula 1’. Having Murray on board meant exactly the same thing to everyone on our team. It was, like: we’ll be OK, Murray’s on board.”

James Allen needed no introduction to Murray. Having grown up in a motor sport family – his father had won his class at Le Mans in 1961 – James had met Murray several times, a relationship that moved onto a more professional basis when Allen began working in F1 in 1990. “I was with the Brabham team in a communications role, which brought me into contact with journalists and broadcasters,” he said. “I had quite a bit of engagement with Murray and always found him very straightforward, very easy to deal with, and very serious about the sport. But there was a great humour and warmth that went with his massive passion for motor racing. I understood that enthusiasm because it came from the same place as mine – as it does if you grow up in a racing family. I always got on really well with him. And then we were thrown in together at ITV, which was hugely exciting.

“Apart from knowing him, I would be working with a legendary broadcaster who was enormously popular with the audience. But Murray did not stand back, take the plaudits and do little else. He really bought into this new era. Before the whole thing went live, he would regularly travel up from his home in Hampshire and become really involved in the production meetings when we covered how we were going to manage everything from the ad breaks to features to taking comments from the pitlane and the studio.”

Hyping up the forthcoming show would be one thing; presenting the first grand prix live, quite another. The buck stopped on Neil Duncanson’s desk.

“We were understandably nervous about the whole thing,” said Duncanson. “There was so much at stake for MACH1, for ITV, for everyone involved. We had 23 hours, or however long the flight took, to think about this on the way to Melbourne. Murray was on our flight – and we just weren’t ready for what happened when we landed. It was like travelling with someone like Bono. We’d never seen anything like it. Getting Murray out of the airport felt to us what it must have been like trying to get Jimi Hendrix out of Woodstock. It was absolutely extraordinary.”

“I knew about Murray’s status as an F1 guru, but this was a real eye-opener,” said Rosenthal. “This mob descended on Murray and they wanted his thoughts on winter testing times; favourites for the race; the Melbourne circuit. What about this? What about that? He was firing back answers with great gusto; happy to share his enthusiasm and knowledge. I could barely remember my own address. He was 73 years of age! I thought it was remarkable that he could do that after a long flight.”

The Australian Grand Prix in Melbourne’s Albert Park felt like the start of a new term for F1 personnel as they gathered in such large numbers for the first time in five months. The ITV crew, in their unfamiliar uniforms, were conspicuous as the new intake for the class of ’97.

“We spent the next few days getting ourselves sorted out; there was obviously a massive amount to do,” said Duncanson. “Everyone wished us well, but you could feel there was a lot of pressure. We were aware that people were saying it was going to be rubbish; the BBC had done it so well – it was real rose-tinted stuff. We were putting commercial breaks into the races, which no one liked – even us. The tension built, and by race morning I have to admit we were all pretty nervous.

“We went down for breakfast on the Sunday morning, and no one’s speaking. We just sat there. Stomachs knotted. Not really feeling like eating. You could read the thoughts: ‘Bloody hell, hope this is going to be OK; what will people think?’ Murray walks into the breakfast room and notices that nobody is saying a word. So, he wanders over to the breakfast buffet and he starts commentating.

‘What will Murray have? Hmmm! Murray’s looking at all the cereals. There’s cornflakes. Look at that! There’s muesli. No! Murray’s not going to have cereal. He’s going for porridge. Incredible!’ We’re sitting watching this as he assembles his breakfast, talking all the way. By the time he reaches the table, we’re in hysterics. Completely broke the tension. We were ready to roll.”

Extract from:

Murray Walker: Incredible! by Maurice Hamilton

Published by Bantam Press on November 11.

Motor Sport readers can pre-order their copy now.