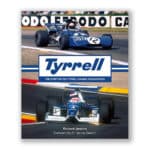

The story of Tyrrell — book review

World titles and plates of sandwiches — a strapping new book on Tyrrell’s history shows what can be achieved within a homely set-up, says Gordon Cruickshank

You don’t get team photos like this any more. The Tyrrell family gathers before the Italian GP at Monza in 1971, with Stewart and Cevert

Grand Prix Photo

A family affair. That was the atmosphere people always commented on after spending time with the original Tyrrell team. The eponymous Ken was a father figure, looking after ace drivers, new boys and dedicated mechanics alike, while his wife Norah was the warm centre of the outfit in the paddock. She even made sandwiches for everyone. Yet this compact unit won grands prix, a constructors’ title and three drivers’ championships with its self-built cars before being bought out and regenerating under a torrent of names. If you DNA-tested today’s Mercedes-AMG F1 team you’d find traces of the Tyrrell genes.

There’s much more to delve into than those F1 successes, though. Richard Jenkins brings to this hefty 480-page book research and interviews going back to Ken’s own racing career in the 1950s in 500s, Formula Junior and F3. Ken gradually realised he was better at organising than driving, and from 1960 was running his own team fielding many future stars including Henry Taylor, John Surtees and “someone who pranced around and made a general nuisance of himself” – a cheeky Scot called Jackie Stewart.

Drawing heartily on many sources plus fresh interviews with surviving team members, Jenkins has a lot to pack in and it can be hard to distinguish recent comments from older extracts. But that’s little matter when the result is a rich weave through the lower formulae into the big time. He has interviewed 30 Tyrrell drivers, so the edit must have been tough, but there are great tales and telling quotes.

Jenkins greatly respects the mechanics and engineers, for example Neil Davis, who gets one of several ‘Tyrrell Heroes’ chapters to himself. Others include Harvey Postlethwaite and designer Derek Gardner, who amazed the F1 world twice, first by springing the team’s first own-design machine on an unsuspecting paddock and then in 1975 causing jaws to plummet earthwards with the six-wheeled P34. An absurd idea – except it won a race.

A recent reunion to launch the book brought together a host of ex-drivers and team members

Don Wales

With Evro as his publisher Jenkins has had decent resources to include many great pictures from the big agencies, but especially enriching are the personal photos from family and team members – a Mini van with a mix of tyres and victory garlands strapped on the roof, mechanics at the workbenches inside the famous woodshed.

Because I’ve read so much about Tyrrell’s F1 adventures it’s a pleasant indulgence to spend time in the F3 and F2 years. Often Tyrrell was running entries for two series in parallel. But at the same time Ken was itching to get into F1. It’s remarkable that he was bold enough to see potential in an aerospace company’s advanced technology including honeycomb construction and load-bearing fuel tanks. It’s even more surprising that the huge Matra firm was willing to go with such a small, if promising, team. But a comment from JYS is telling: “What a lot of people don’t appreciate about Ken is what a brilliant negotiator he was. Jean-Luc Lagardère [Matra MD] had a reputation as a tough negotiator, yet Ken dealt with him in a masterful way.” He even persuaded Matra to build him the DFV-powered MS10 while it was sorting out its complex V12.

Thus a government-funded engine and chassis programme which needed a winning driver came together with an ambitious team and a champion-to-be, although it’s ironic that Jenkins points out the reason Lagardère wanted to diversify Matra, a major rocket and missile maker, away from military products was because “peace and stability [had] generally settled across Europe”. Oh, those distant days…

Tyrrell’s own cars tended to be solid and straightforward, yet there was cutting-edge thinking: interesting to see drawings of Maurice Phillippe’s own discreet fan car that ran in 1977 before the Brabham BT46B. It was intended for engine cooling as well as some downward suction but when its engine overheated at Paul Ricard the team abandoned it. There was also a semi-active suspension proposal before Colin Chapman’s supremely effective Lotus 78 pitched the Hethel team streets ahead.

Naturally Stewart is the pivot of the tale as he pilots the team to greatness but Jenkins has much to say on the after years, especially the hard way the team was treated over the 1984 lead shot incident, disqualified for an entire season. Even though we know the story arc it’s hard not to feel excited at flashes of success such as Jean Alesi’s two second places in 1990. But the trend was deflatingly down, leading us to more firm opinions on the team’s end, steamrollered by “arrogant” suits at BAR and the “pompous and patronising” Craig Pollock.

Jenkins says: “It was important not to get too bogged down in race summaries and results.” Hear, hear. It lets him concentrate on the people who made the team. Naturally some races get the spotlight, not least the awful day at Watkins Glen in 1973 when the brilliant François Cevert died, but this is really about Ken Tyrrell, a decent, principled man who over 40 years inspired supreme loyalty in his ‘family’ and admiration and affection from the paddock. And from Richard Jenkins.

|

Tyrrell: The Story of the Tyrrell Racing Organisation

Richard Jenkins Evro Publishing, £90 ISBN 9781910505670 |