Darrell Waltrip: talking the walk

From rent-a-quote young upstart to wise old hand, three-time Winston Cup champion Darrell Waltrip played a crucial role in NASCAR's rapid growth of the 1970s and '80s. Paul Fearnley talks to this showman who never shirked the nitty-gritty

Winner at Daytona in 1989

ISC Archives/CQ-Roll Call Group via Getty Images

Bristol Motor Speedway in Tennessee sorts out the Good Ol’ Men from the Boys. Even the 650-feet straightaways on the World’s Fastest Half Mile’ are banked — at 16 degrees, no less. Its turns crank to a rib-crushing 36. Such curvature means speeds here are 30mph up on those at Martinsville — the other throwback skin-and-bone half-miler still on NASCAR’s punishing, but forever-modernising, Winston Cup schedule. To top the timesheets at Bristol is to meld courage and conviction in a 125mph groove.

Not that rolling round on pole here means an awful lot, for there are still 500 dizzying, push-and-shove laps between you and victory. A tough ask. But you have to win at Bristol if you want to be called a real NASCAR driver.

Darrell Waltrip was called everything but that when he breezed onto the scene full-time in 1973, the second year of Winston’s sponsorship. NASCAR was a very different world back then. It wasn’t slick, it wasn’t blue-chip, and it was far from being the second-biggest motor-racing championship in the world. Barring the Daytona 500, it was a little bit Hicksville. The large checks [sic] were on the shirts, not in the banks. Richard Petty, David Pearson, Cale Yarborough and Bobby Allison were rightly feted by the hardcore, but they had yet to gnaw at the soft underbelly of America’s public consciousness. They were fearsome competitors, sure, hardened by week-in-week-out competition, but they were hardly media darlings.

Enter 26-year-old Waltrip. A Tennesseean by birth, but racing out of Owensboro, Kentucky, he was used to winning in the lesser, “Saturday night” races, and saw no reason for his sequence of success to stall in this more rarefied atmosphere. At least that’s what he told everybody — any time he could. Never short of a quote, he’d fire off opinions about his own race and everybody else’s, if need be. Yarborough,the epitome of a pre-Waltrip stock-car driver (and, to be fair, for a good while post-) nicknamed the new kid ‘Jaws’, ‘cos his mouth never stopped moving. Waltrip mischievously painted a shark on his car’s flank and invented ‘Cale Scale’, a from-one-to-10 dig at this laconic driver’s tendency to label every just-finished race the ‘toughest he’d ever run’.

The first of four consecutive wins in 1981 came at Martinsville

ISC Images & Archives via Getty Images

“He’d climb out of the car, as red as a beet, sweating, worn out, just exhausted, and say the same old thing,” remembers Waltrip. “I used to think, ‘Toughest compared to what?’Hence ‘Cale Scale’.

“The whole thing about that time was that there was a select group who won all the races, and they were very protective of their turf. When I came in as a young guy, they acted like they didn’t care I was there. They didn’t want you there. They didn’t know your name. They didn’t want to know your name. And that was a big change to what I’d been accustomed to. I’d been the show, not part of the show. They wanted you to be a small part of their show, but! didn’t go along with that

“I was probably more obnoxious than I should have been, but I saw that it got results, and when you get results you parlay that into whatever you can. Being outspoken and dressing a little different — no big belt buckle, no moustache, no jeans — gave me a lot of notoriety. And I used that to my advantage.”

No amount of attitude or trend-bucking was going to soften the inevitable hard knocks, though, and it took Waltrip until 1975 to score his maiden win — the Music City 420 at Nashville Raceway. He had to wait another three years for his first Bristol victory, besting Benny Parsons by a lap to take the spoils in the Southeastern 500.

The wins were starting to flow now.

The following year, ‘King Richard’ pipped him to the title by a measly 11 points. Petty had always been his target, and he’d come agonisingly close to usurping him with his self-run team. Close enough to know he needed a little help; close enough for everybody else to know he was a future champion given the right equipment.

“There were only three or four big teams when I started — the Pettys, Junior Johnson, the Wood Brothers — so if you wanted to get into racing you had to build your own cars, set up your own team, have your own people around you. I took very little and did a whole lot with it. That’s what got me noticed.

“It’s very gratifying to win a race for anybody, anytime, that’s what your goal is, but there’s no better feeling to know you did it in your own car run by your own team. But it’s also very wearing, building engines, building cars, driving the team truck, just so you can race for those four hours on Sunday. I needed to be more focused on driving. Plus I’d learned I preferred my name at the top of a cheque rather than the bottom.”

Waltrip signed for Junior Johnson’s top-line outfit in 1981. And took the championship, scoring back-to-back Bristol wins in the process — a pattern he repeated in ’82. Incredibly, he topped out both Bristol races in ’83 — only to lose the title to Bobby Allison by 47 points. Six consecutive wins on NASCAR’s toughest track. No, make that seven — he won the first race there in 1984. Staggering. And there’s more. He won 12 times at Bristol. And 11 times at Martinsville. This talker could walk the walk.

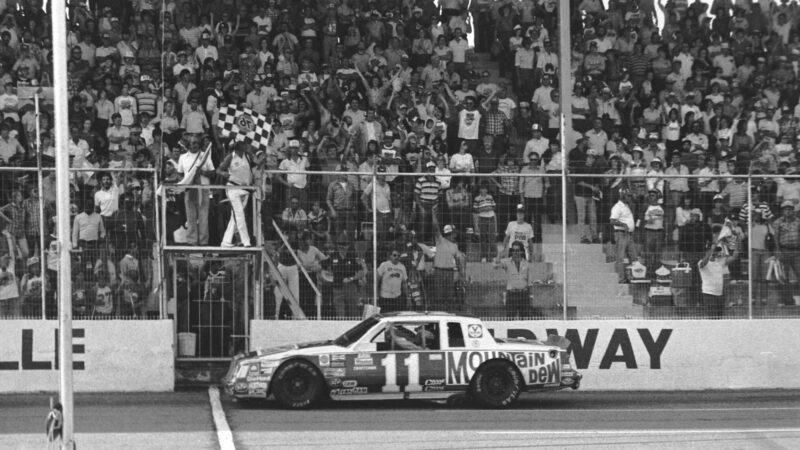

Waltrip went back-to-back to secure his second title in 1982 with Junior Johnson’s Mountain Dew team

ISC Archives/CQ-Roll Call Group via Getty Images

In the early to mid-80s, during a six-year, 43-win, 34-pole spell with Junior, Waltrip was almost unbeatable on the short tracks, matching his natural speed with a miraculous tactical acumen: nursing, manoeuvring, nerfing, outguessing, squeezing and then, and only then, attacking.

“It’s difficult to explain what we do on those kind of tracks. It’s basically instinctive. I think you can teach someone to road-race, there’s a basic technique to that; round-track racing is something you must have a feel for. You don’t think about what you’re doing, you just kinda react. And you have to be comfortable doing it. That’s the big thing.

“It’s all about track presence, knowing where you are all the time, and knowing where the competition is. A mental picture. But that’s something you paint in your mind; it’s not a photograph you can take away with you and study, it’s something that’s changing all the time. And with all of this going on, you have to be thinking ahead too, way ahead.

“I always liked to be the guy in and around the first 15 or so during the first couple of hundred laps, the top five for the next couple of hundreds and, when the race was won, I wanted the rest to say, ‘How did he do that?’

“Junior’s cars and his team were just so consistent I had great faith in them. If we didn’t win, we’d be second, third or fourth. That’s how we won titles.”

They might have been his happiest hunting grounds, but it wasn’t just about the half-miles: he racked up 32 super-speedway victories in a 28-year career, including a record six in Charlotte’s awesome 600-miler. He scored five road-course victories, too. His feats must satiate even the most ravenous when-and-where junky: 84 wins, 58 poles, 276 top-fives, almost $20m in prize money.

There were downs too. You’re bound to get them if you start 795 races. A huge Daytona practice crash in 1990 left him with serious leg injuries. He recovered to score two wins in ’91 and three more in ’92, but these were the last hurrahs of a career that went past its sell-by date. Like all hotshoes, he’d boasted he’d never race past his prime, past 40.

He was 53 when he eventually retired in 2000. Nobody minded, legends are cut some slack. No, correction, not legends. Better than that. Real-deal NASCAR drivers.