Denny had barely travelled within his own country, so the trip to England was a major expedition. It was made a little easier by the fact that his sister had been working in Europe for a year, and was able to help out: “I met them off the train in London with Bruce McLaren, who gave them a Morris Minor to use. We had to go to a lunch somewhere, and I was saying to Denny, ‘Left here, right there’, and he said, ‘I’m not driving in this bloody traffic!’ and made me take over.”

Hulme didn’t know Lawton well, but the pair lived together and were just getting acquainted when George was killed over at Roskilde in Denmark, as Anita recalls: “Denny stopped his car and got out, and George died in his arms. It was a major shock.”

“He still wanted to continue,” continues Greeta, who’d stayed home. “I felt that I had no right to say, ‘Don’t you do it, because I’m frightened.’ It was still something that he had to do. My role was to patch him up and send him back until he’d had enough.”

Hulme finished the season and then returned to contest the New Zealand GP, and took the opportunity to get engaged to Greeta.

“We decided that we still felt the same about each other,” she says. “What’s that saying — absence makes the heart grow fonder? But he decided to continue racing.”

The scholarship funding ended with the GP, and Denny was now on his own. He sold his car, returned to Britain and helped build a new Cooper. Later Greeta embarked on an epic three-day flight to join him, and at first she lived in the bedsit in Kingston previously occupied by Pat McLaren, who’d just married Bruce. She soon found work as a staff nurse, arranging the schedules so that she had weekends off.

Having recently learned to drive Greeta shared tow-car duties as she and Denny toured the Continent. “It was us two versus the world,” she smiles. She still owns their original Ford Zodiac.

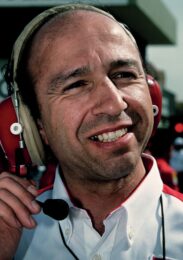

Victorious in Germany in championship year, alongside team boss / team-mate Jack Brabham

Grand Prix Photo

Hulme made good progress on the tracks and subsequently found rides with Ken Tyrrell and later Jack Brabham, for whom he also worked as a mechanic. He was the pacesetter in Formula Junior in 1963, and then shone in Formula Two the following year.

“What came through in the end was that you had to be in the right place at the right time to get the breaks,” says Greeta.

Hulme made his Formula 1 championship debut for Brabham at Monaco in 1965, and finished fourth second time out at Clermont-Ferrand. Inevitably, it wasn’t always easy being in a team owned by the other driver, as Greeta admits: “Denis was always careful that he didn’t tread on Jack’s toes, played it quietly, and did what was expected of him. It was all unspoken.”

He had a great season in 1966, starring in F2 with the Brabham-Honda, finishing second for Ford in the formation finish at Le Mans, and taking four grand prix podiums as he supported Jack’s successful title campaign. But ’67 was to be his year, as he won in Monaco and at the ‘Ring to set up his own title triumph in the last round in Mexico City.

“Denis knew all he had to do was follow Jack around, and he’d have enough points to beat him,” says Greeta. “There was nothing Jack could do. He couldn’t reverse into him and shunt him off!” Brabham finished second and Hulme third, and Denny was world champion by 51 points to 46.

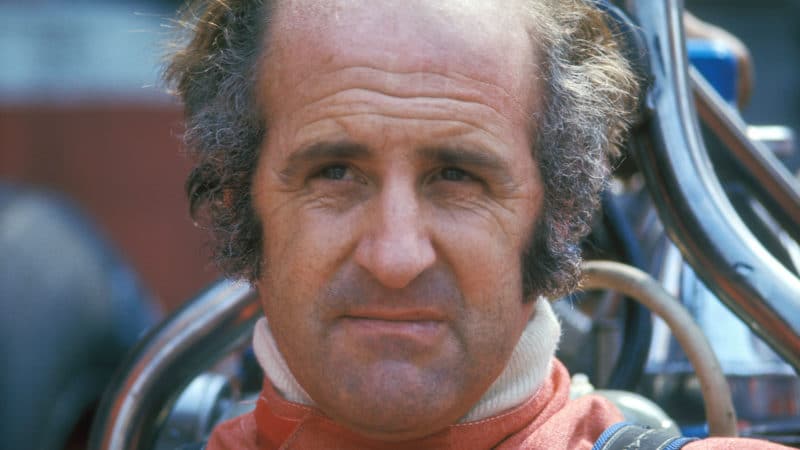

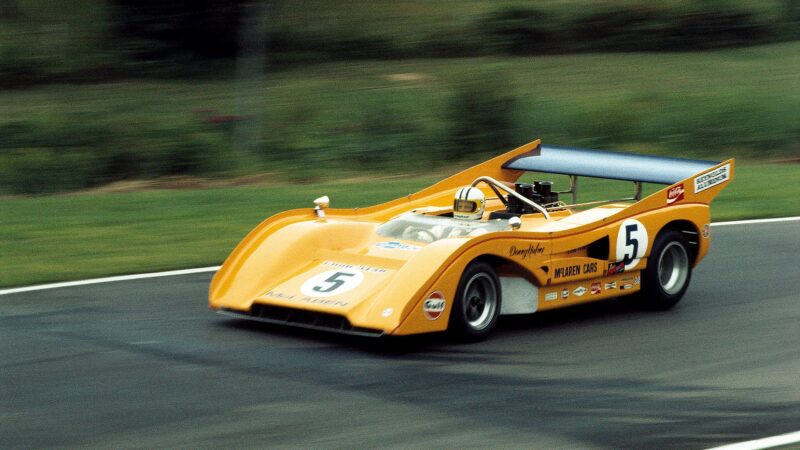

Hulme felt right at home in Can-Am – pictured here for McLaren at Mid-Ohio ’71

Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images

For the following season he joined his old pal McLaren, with whom he enjoyed a much closer relationship than he ever had with Brabham. The DFV-powered M7A was a great car and Denny very nearly won the world title for a second time in 1968, late-season victories in Italy and Canada putting him in contention in Mexico once again. On this occasion he didn’t make it, but the Can-Am title provided compensation.

Hulme loved that sports car series, and it was in the States that he picked up his nickname ‘The Bear’. Never one to seek the limelight, he did not have much time for the media, though occasionally he would be difficult purely for his own amusement.

“They would ask him the most stupid questions, just before a race,” remembers Greeta. “I’d learned to leave him be. He did not tolerate fools. But over the years he did mellow a bit.”