Scottish Trial and Hambledon Rally

Overall winner the VSCC Scottish Trial was RG Winder (Austin 7), and other first-class award winners were P Stringer (A7), J Evans (GE A7), J Blake (ON), and J Ghosh…

Max Verstappen, aged 21, presently in his fifth full season as a fully-fledged Formula 1 driver? The notion would once have seemed ridiculous.

When the F1 World Championship commenced at Silverstone in May 1950, the average age of the 23 participating drivers was just south of 39, that of the three podium finishers 44. Geoffrey Crossley was the only starter yet to toast his 30th birthday.

Different times, of course. Racing’s war-imposed cessation had deprived many drivers of what should have been their competitive prime and there had likewise been technological stasis: that landmark Silverstone race was dominated by the Alfa Romeo 158, a car whose roots could be traced to 1937.

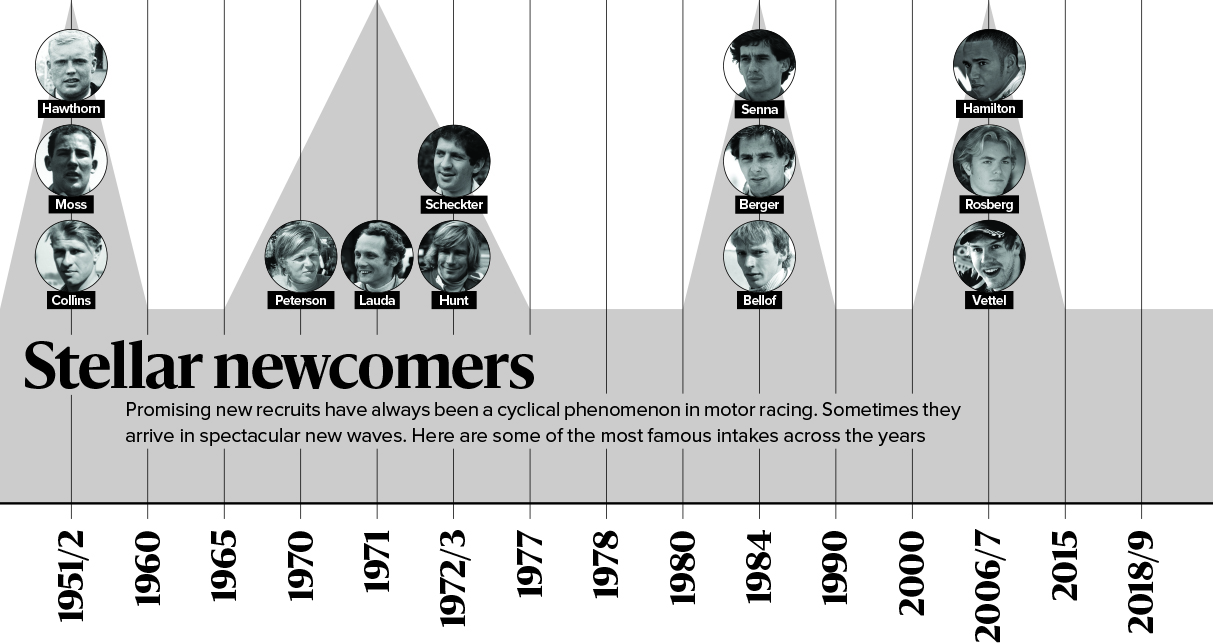

It took a while for the grand prix demographic to shift: youngsters such as Stirling Moss, Mike Hawthorn and Peter Collins broke through during the early 1950s, but Juan Manuel Fangio was still accumulating titles – his fifth, in 1957 – at the age of 46.

In 1959 Bruce McLaren, 22, became the youngest winner of a world championship grand prix, a benchmark that endured until Fernando Alonso’s maiden F1 victory at Budapest in 2003 (though it has twice been lowered since). Fledgling future greats tended to trickle into the sport’s upper tier through the 1960s – Jim Clark and John Surtees in 1960, Jackie Stewart and Jochen Rindt in 1964-65 – but the pace of significant graduation accelerated at the following decade’s dawn. Emerson Fittipaldi and Ronnie Peterson made their debuts in 1970 and Niki Lauda the following year (although it took a couple more for the Austrian’s gift to become apparent), with Jody Scheckter and James Hunt following in swift succession.

There have been occasional multiple reboots ever since, for instance Villeneuve, Piquet, Arnoux and Pironi emerging in 1977-78, Button, Montoya, Alonso and Räikkonen in 2000-01 and Rosberg, Hamilton, Vettel and Kubica in 2006-07.

The present campaign feels similar. In reality Verstappen is slightly old news, but inescapable youth and an aptitude for creating headlines keep him fresh. Charles Leclerc is the first raw youngster since Gilles Villeneuve to have been trusted with a Ferrari race seat – and he has made much of the opportunity, being unlucky not to win in Bahrain (only his second start for the team) and coming within a Verstappen-sized lunge of breaking his duck in Austria. He has also outpaced decorated team-mate Sebastian Vettel on several occasions.

The ultimate potential of the latest rookies is trickier to assess. Lando Norris has an upper-midfield McLaren at his disposal and has made impressive use of it, so much so that the team has already extended his contract until the end of 2022. Having been dropped and then rehired by Red Bull – fast becoming a trend with the energy drink manufacturer’s driver academy, given the extent of previous culls – Alex Albon’s turn of speed has perhaps been one of the campaign’s surprises, even though he finished third (just behind Norris) in last year’s FIA F2 Championship. He crept into F1 slightly below the radar, having initially committed to race for Nissan in Formula E instead. George Russell should be assessed not so much for doing as well as he can in the hamstrung Williams FW43, but for the fact he comfortably beat both Norris (one win) and Albon (four) in F2 last year. He scored seven victories… and only patchy reliability prevented him accumulating several more.

When they made their respective F1 debuts, these last five named had an average age just shy of 20.

It’s not just that the sport has got younger, but the methodology has also altered significantly. If we consider some of the intake from the early 1970s, Peterson’s progress was abetted by the generous backing of private benefactor Count ‘Gughi’ Zanon di Valgiurata; Lauda took out a vast bank loan (without the remains to repay, until his vim at the wheel of a BRM led to a phone call from Ferrari); Scheckter earned a scholarship to race in Europe in 1971, continued to win after graduating from Formula Ford to F3 mid-season, signed a McLaren F2 contract for ’72 and had made an impressive GP debut with the team before the year was out; Hunt fused success with setbacks until aristocratic enthusiast Lord Hesketh offered him a chance and subsequently smoothed his path to F1. Back then racing careers were more likely to start at 18 than eight.

The modern generation tends to have competed for several years before getting anywhere near a car – and the best are usually snapped up some time before they’re eligible for a road licence: Lewis Hamilton and Norris by McLaren, Sebastian Vettel by Red Bull, Leclerc by Ferrari and Russell by Mercedes. Verstappen is promoted as a Red Bull driver, but was nothing of the sort until the later stages of his lone F3 season in 2014; he was still only 16 when an impending F1 race seat with Toro Rosso was confirmed. It’s all about maintaining physical and mental fitness, media training, data acquisition and simulation tools.

Scheckter once had to craft his own roll-cage from exhaust tubing, so that he could legitimately race the Renault 8 in which he forged a name for himself in his native South Africa. The days of such initiative are probably past.