Bugatti EB 110 SC: The lone ranger

In 1994, Bugatti’s return to the track was loaded with sentiment but the car didn’t follow the script. Étienne Raynaud joins the owner of the firm’s last modern racing car at the scene of its final race

REMI DARGEGEN

It’s a glorious day at Dijon- Prenois, the French Grand Prix’s former home that sweeps through the Burgundy countryside. Formula 1 has not raced here since 1984, but the venue remains very active and retains a significant but perhaps overlooked distinction: 25 years ago, this is where Bugatti made its final appearance in contemporary motor sport with the car you see here, an EB 110 SC (Sport Competizione) entered by the Monaco Racing Team for the Two Hours of Dijon.

In the hands of experienced race/rally driver Bertrand Balas and MRT owner Gildo Pallanca Pastor, it finished third in the opening heat but retired from the second following a collision.

Since that day, Bugattis have competed only in historic and vintage events.

Only two official EB 110 racing cars were built; an LM for Le Mans in 1994 and this SC for participation in IMSA and the BPR Global GT Series

REMI DARGEGEN

To mark the end of that era for the marque, the current owner of the EB 110, a European Bugatti collector, has brought it back to Dijon for today’s test drive exactly a quarter of a century on. “The SC is maintained in perfect condition,” he says. “I promised myself to have it driven in all the places that have been landmarks in Bugatti’s fascinating race history. Being here today at the Dijon- Prenois track with the EB 110 SC, the last works racing car of Bugatti, 25 years after the final [period] race of a Bugatti, is one of these important moments for sure.”

Bugatti’s track record includes a cluster of grand prix wins in the 1920s and 1930s, five straight Targa Florio victories from 1925- 1929 and Le Mans 24 Hours conquests in 1937 and 1939. The firm lost direction, however, following the Second World War; founder Ettore Bugatti died in 1947 and eldest son Jean –a gifted engineer and Ettore’s natural successor – had perished eight years beforehand when he crashed a Type 57C on roads close to the Molsheim factory. Another son, Roland, attempted to keep the business going, but it was soon in serious decline.

Bugatti’s final grand prix car, the T251, was distinctive – it featured a transverse straight eight! – but not terribly competitive; Maurice Trintignant drove it in the 1956 French Grand Prix, its only appearance. The firm continued making parts for the aircraft industry until it was purchased in 1963 by Hispano-Suiza, at which point it seemed unlikely that any car would again be adorned by its famous Macaron badge.

REMI DARGEGEN

The ‘Sports Competizione’ was a revamped EB 110 Super Sport that was lightened for the track

REMI DARGEGEN

REMI DARGEGEN

Until…

In 1987, Italian Romano Artioli –a successful entrepreneur and major Ferrari dealer who would later also acquire Lotus – bought the rights to use the Bugatti name and spared little expense in bringing the brand back to life. A state-of-the-art factory was built in Campogalliano, Italy, about 20 miles from Ferrari’s Maranello HQ, and the Lamborghini Countach’s creator Paolo Stanzani was hired as technical director. He moved on before the project was complete and his place was taken by Nicola Materazzi, whose previous credits included the Ferrari 288 GTO and F40.

The EB 110 featured a carbon monocoque, 3.5-litre quad-turbo V12 that generated 560bhp at 8000rpm and four-wheel drive, the latter contributing to relative heft for a GT, at 1920kg. It was launched to great fanfare in Paris on September 15, 1991 – the 110th anniversary of Ettore Bugatti’s birth – with film star Alain Delon at the helm.

The impetus to put the car on track came from French press mogul Michel Hommell, who dreamed of taking the marque to Le Mans in 1994, 55 years after its second – and most recent – victory. That led to the creation of the EB 110 LM, after a hectic sixmonth development programme between Bugatti and Le Mans-based engineering firm Synergie. Loris Bicocchi, Bugatti’s test driver from the dawn of the Artioli era, says: “It was extraordinary, everything was ambitious – even a little crazy. But the Bugatti story was crazy from the start, so it all made sense…”

The SC’s involvement in its final race here was short-lived, with a crash on the second race

REMI DARGEGEN

REMI DARGEGEN

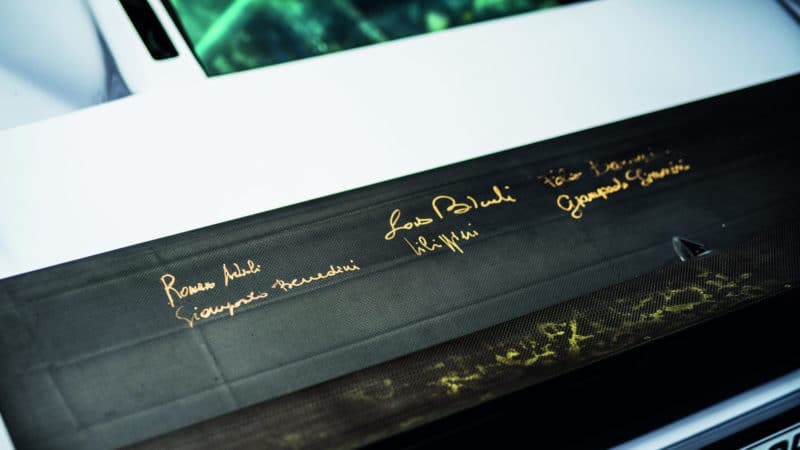

Notable signatures include Bugatti chief Romano Artioli and designer Giampaolo Benedini

REMI DARGEGEN

Veterans Alain Cudini and Jean-Pierre Malcher were hired to race the car alongside Eric Hélary, 1990 French Formula 3 champion and Le Mans winner three years later with Peugeot. When Malcher was sidelined by illness, rising star Jean-Christophe Boullion stepped in to replace him.

In 1994 Le Mans was run to GT regulations, but German team Dauer exploited a loophole by converting a Group C Porsche 962 to road specification… and then switching it back again. It was by far the fastest thing on track, but the Bugatti was among the quickest of the pure GTs. Its chances were compromised before the start, however, when Synergie discovered a fuel leak. The only solution was to patch up the damage with Araldite and run the car on halftanks for the first couple of stints, while the repair cured. Once it was able to run properly, the Bugatti moved up into the top six before being delayed by turbo problems. A finish still appeared to be achievable, but Boullion speared into the barriers during the final hour as the result of a suspected puncture.

For all the disappointment, the car had shown potential and that’s how gentleman racer Pastor became involved. He visited Bugatti late in 1994 to outline ambitious plans for his Monaco Racing Team to run a brace of EB 110s in the US-based IMSA championship, fledgling BPR Global GT Series and Le Mans.

This led to a concentrated weight reduction programme, refined aerodynamics and significant adjustment of the engine mapping in a bid to avoid any repetition of the turbo problems that afflicted the car at Le Mans. The uprated version was known as the EB 110 SC.

Bicocchi: “One of the biggest differences between the LM and the SC is that Bugatti was able to work on the suspension by changing the kinematics, designing a new hub, studying the stiffness of the springs and calibrating the dampers. The original Le Mans car was made too quickly; we took important ideas from it.”

In addition, Pastor also targeted a new icespeed record. Artioli agreed to provide a production EB 110 SS and Pastor reached 181.14mph across Lake Oulu in Finland, which would remain unbeaten for 18 years.

While that generated positive publicity, the reality of Bugatti’s situation was different. The EB 110 had not proved very profitable, a situation compounded by the long and costly process of homologating it for the American market. With Bugatti’s situation looking increasingly precarious, suppliers began to shy away from any competition programme and MRT had to scale down its ambitions: it had hoped to buy three cars, including a spare, but in the end Bugatti was able to build only one.

Monegasque businessman and racer Gildo Pallanca Pastor owned the Monaco Racing Team while still in his twenties

REMI DARGEGEN

The car made its debut in the Watkins Glen 3 Hours on June 24, Pastor and former grand prix driver Patrick Tambay finishing 19th overall and fifth in class. One month later, the same pair took 16th/sixth at Sears Point, before the car was freighted to Japan for Pastor and Hélary to contest the Suzuka 1000Kms. Gearbox trouble forced their retirement and the car subsequently returned to Campogalliano for repairs. It was still in the workshop when Bugatti was placed in receivership that September; MRT had to obtain a court order to reclaim its car and would henceforth be responsible for its maintenance.

“I like the McLaren F1, but the EB 110 had many more innovations”

In the hands of Pastor, Derek Hill and Olivier Grouillard, the car ran in the 1996 Daytona 24 Hours, qualifying second in class and running as high as sixth overall after two hours, but gearbox gremlins struck and the car retired.

Pastor and Tambay shared the car during pre-qualifying at Le Mans, but they failed to make the cut for the 24 Hours after the latter crashed. Six weeks later came Dijon, a swansong for both car and – until current owner VW decides otherwise – marque. It was the end of a journey fuelled by fierce ambition, but stifled by a shortage of resources.

The SC at the 24 Hours of Daytona in February 1996, among a field heavy with Porsches

DPPI

Bicocchi has driven the EB 110’s period rival the McLaren F1 and says: “I like the McLaren and its BMW V12 sounds incredible, but I think the EB 110 had many more innovations: an in-house five-valve-per-cylinder engine with an integrated transmission in the engine block, four-wheel drive, six-speed gearbox, a carbon monocoque chassis, ABS…” Andy Wallace has also driven both (he shared the third-placed McLaren at Le Mans in 1995) and describes the Bugatti as “way ahead of its time”.

After Dijon, MRT repaired the EB 110 and Pastor retained it, now road registered, until 2015. The current owner still uses the car regularly and Dijon ticked off another Bugatti landmark in his mission. The US now awaits.